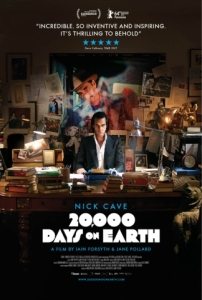

20,000 Days On Earth is a dramatized documentary of a day in the life—the 20,000th day in the life—of Nick Cave, who, if you aren’t aware, is an Australian rock star, or sort of rock star, which is to say he’s certainly a star, but his music isn’t easily categorized, and this curiously part-fiction, part documentary is likewise a movie not easily categorized.

20,000 Days On Earth is a dramatized documentary of a day in the life—the 20,000th day in the life—of Nick Cave, who, if you aren’t aware, is an Australian rock star, or sort of rock star, which is to say he’s certainly a star, but his music isn’t easily categorized, and this curiously part-fiction, part documentary is likewise a movie not easily categorized.

Which is wholly the point. When approached by writer/directors Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard about their making a doc of his life, Cave said no. He wasn’t interested in subjecting himself to a typical music documentary. So something else was conceived. Something like a documentary that isn’t a documentary. Or else it is, but it’s a documentary where the subject isn’t Nick Cave but the version of Nick Cave Nick Cave plays in the documentary, the same Nick Cave Nick Cave plays on stage, and possibly the only Nick Cave there is anymore.

As Cave puts it, referring to a scene in the movie where he talks with actor Ray Winstone:

Well, you know, I was talking to an actor—I’m talking to Ray Winstone—and their job is to reinvent themselves. Their job is to be different characters, and I think I was trying to make the point with Ray that it’s a very different thing between my job and his job. There is only one character. There is only one mask, and eventually that mask kind of calcifies itself onto the face and you can’t take it off anymore, and you just become that thing. This is all sounding a bit bleak, but actually it’s quite a wonderful thing as well.

Who is Nick Cave? Do we see him in the movie? We definitely see a Nick Cave. It’s the one we know if we’ve listened to his music.

Cave provides narration throughout the film, giving the production the feel of one of his songs. We see him wake up in the morning with his wife, drive around town, write at his desk, play his piano, eat lunch with friend and bandmate Warren Ellis, watch Scarface with his kids. These scenes are on the one hand real—this is what Nick Cave does in life—but they are also staged.

We see Cave talking to a psychoanalyst, Darien Leader, answering questions about his father, his first sexual experience, his childhood. It’s staged. We’re not seeing an actual psychotherapy session. Cave had never met Leader before. But Leader is in fact a psychotherapist, and Cave did in fact sit and talk to him over two long days of filming, without knowing in advance what Leader would ask him. So is this “real”? Or “fake”? Does it matter? The conceit forces Cave to face questions far more interesting than those of a typical interviewer, in a setting more conducive to eliciting thoughtful answers.

In other scenes Cave drives a car through the rain, alone until various people appear beside him as in a dream, as though Cave were hallucinating his passengers. One of them is Ray Winstone. Another is Kylie Minogue. Cave isn’t actually driving in the scenes. He’s only pretending to. These scenes are purely cinematic constructions. But the conversations are unscripted and revealing.

Cave visits the Nick Cave archive in his hometown of Brighton where he looks through writings and photos from his childhood, pointing himself out among the other children, telling stories from the times they were taken. He walks us through a series of photos from an early performance of his first band during which a “fan” wandered up on stage and pissed on it.

Only there is no Nick Cave archive in Brighton. This too is a contruct. A strange and effective one.

The overarching conceit of this being a day in the life of Nick Cave is as surreal as the smaller conceits making it up. What links the day together is the creation of a new Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds album (last years’s Push The Sky Away), with the focus on one song, “Higgs Boson Blues.”

Cave plays snippets of the song alone on the piano. Later he and the Bad Seeds record a version of the song, with Cave directing the band from behind his piano, they having never played it before. And finally, at night, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds perform the song before an audience, in a sequence as mesmerizing as an actual Nick Cave show, which if you haven’t seen one, you should.

I’m a fan of Nick Cave. If you are too, I expect you’ll be a fan of the movie. If you don’t know Cave’s music, you might still be a fan of the movie. It’s unique among the boring world of rock documentaries. And while it never peels back the mask Nick Cave has spent a lifetime molding to his face, it’s nevertheless a revealing portrait. One he painted himself.