Woe be to Spartacus, Stanley Kubrick’s bastard child of a movie, hugely popular when released, later to be disowned by its director. It contains flashes of Kubrick’s genius, but just as often resembles the standard Hollywood epics of the era. It features a hero in Spartacus unlike any in Kubrick’s ouevre, a man with no shades of grey, who never questions his own actions, who is, simply, a hero. Is there anything duller?

Woe be to Spartacus, Stanley Kubrick’s bastard child of a movie, hugely popular when released, later to be disowned by its director. It contains flashes of Kubrick’s genius, but just as often resembles the standard Hollywood epics of the era. It features a hero in Spartacus unlike any in Kubrick’s ouevre, a man with no shades of grey, who never questions his own actions, who is, simply, a hero. Is there anything duller?

Kubrick was brought on board two weeks into shooting, after star/producer Kirk Douglas fired director Anthony Mann. Kubrick had previously directed Douglas in the brilliant Paths of Glory (’57), and despite Spartacus having a budget far in excess of anything Kubrick had worked with before ($12 million), Douglas wanted him.

Kubrick didn’t like the script, but presumably he saw the advantages the movie would have for his career. And it did have advantages. It showed he could work with a large budget on a large production, it was financially successful, and it allowed Kubrick to never again do anything like it. As he later said:

If I ever needed any convincing of the limits of persuasion a director can have on a film where someone else is the producer and he is merely the highest-paid member of the crew, then Spartacus provided proof to last a lifetime.

And:

Although I was the director, mine was only one of many voices to which Kirk listened. I am disappointed in the film. It has everything but a good story.

The screenwriter, Dalton Trumbo, assumed his pseudonym would appear in the credits. He’d been blackisted in the McCarthy era for refusing to name names during the Communist witchhunt and hadn’t had a screen credit under his own name since (despite having continued to write produced screenplays). But when it came time to assign credit, Douglas, sick of the bullshit blacklist, put Trumbo’s name onscreen, marking the end of that sad chapter of Hollywood history (not that some writers didn’t continue to be screwed afterwards).

Trumbo wrote the script, based on the book by Howard Fast, in, it is said, two weeks. It shows. It’s bloated and meandering and often lousy. Of course much was rewritten during shooting by Douglas, Fast, and Kubrick, how much by whom it’s impossible to say. And it’s by no means all lousy. There are fine speeches here and there, and the character of Batiatus (Peter Ustinov), the comic relief of the movie, is blessed with endless hilarious lines. Ustinov almost steals the movie. He would have if not for Laurence Olivier as Crassus. Olivier, as you may have heard, can act. He’s stunning. He commands every scene he’s in, even when he’s not speaking. He makes Kirk Douglas look like, well, like a movie star.

Douglas isn’t bad. He does his dead stare as ominously as ever. But I never cared about Spartacus. The nature of the character is an obstacle Douglas never gets over. Spartacus has no depth. He’s a really, really, really good good-guy. The slaves love and respect him, the beautiful Varinia (Jean Simmons) falls for him on first sight, and Crassus secretly wishes he could be as bold and brilliant and beloved. He’s boring. I prefer Douglas when he’s playing less savory characters. Ace In The Hole and Out of The Past come to mind.

Also boring? Much of the movie. Spartacus is outrageously long. Long movies were all the rage starting in the mid-‘50s for about a decade. The “epic” was in. Presented in the brand new CinemaScope format, nothing kicked dirt in the face of television like a lengthy, bloated historial epic with ten thousand extras on hand. Douglas was itching to be cast in Ben-Hur, but was passed over for Heston. In Spartacus he saw his chance to go big and Roman.

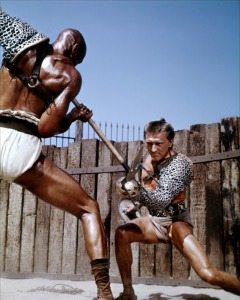

The story concerns a slave, Spartacus, trained to be a gladiator, who escapes gladiator school with his buddies and forms an army. He leads his men south with the intention of hiring pirate ships to sail them the hell away from Italy. Meanwhile, in Rome, the senate (led by Charles Laughton as Gracchus) isn’t happy about the slave revolt, but they hardly take it seriously enough. Crassus is looking forward to the day when he can bring his legionnaires into Rome and be done with the whole “republic” business. On hand to help him is a young fellow by the name of Caesar, who likewise seems keen on this notion, wouldn’t you know. Off they go to meet Spartacus’s army, now headed to Rome after having their pirate ship plan thwarted by scheming Roman senators.

Kubrick being Kubrick, he dug into the actual history of events, and wanted the movie to reflect them more honestly. But Kubrick wasn’t calling the shots. So for example, to explore what really caused Spartacus to give up running and attack Rome—a big unknown to history—risked introducing moral ambiguities in a character Douglas saw as purely heroic.

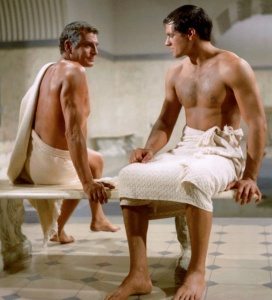

Speaking of ambiguities, a number of scenes were cut from the original release, most notably the one in which Crassus, naked in his hot bath, chats with his new slave, Antonius (Tony Curtis), about whether he enjoys eating oysters or snails or, like Crassus, both. It’s a not exactly subtle way for Crassus to get as his flexible sexuality, and, alas, causes Antonius to flee to the embrace of Spartacus’s slave army, which he seranades with his lovely voice. Apparently the studio felt Crassus’s argument that homesexuality was not a matter or morals but one of taste not suitable for American audiences.

Unsuitable for any audience are the romantic scenes between Spartacus and Varinia. The characters are boring, the dialogue is ripe, and the sets are certainly sets. The best scenes are any with Olivier and Ustinov. Visually, Kubrick gets the most Kubrickian with the final battle, and the wide, distant shots of the Roman army marching in formation across the field of battle, before cutting to tight shots of the slaughter. For the most part, there’s little in Spartacus that cries out “Kubrick!” The lighting in some of the interior tent scenes stands out. Shot composition is always nice to look at. And yet there’s still the sets and costumes and overall ‘50s epic visuals to get past, if you can.

I couldn’t. I gave Spartacus every chance to impress. I watched a clean, 35mm ‘Scope print at the Castro Theatre, but in the end Spartacus feels less important as a movie to be watched than as a necessary step in Kubrick’s career. It marks the dividing line between the small pictures he’d made before it to the larger ones to follow. Its success gave him leverage and respect he didn’t have before (not to mention a paycheck. Kubrick never received any money for directing his first four films. The first time he was paid as a director was for a movie he didn’t end up directing, One Eyed Jacks, immediately preceeding Spartacus). And the experience of making it, of being a hired hand, proved to him he could never put himself in that place again.

Kubrick sums it up so:

Then I did Spartacus, which was the ony film that I did not have control over, and which I feel was not enhanced by that fact. It all really just came down to the fact that there are thousands of decisions that have to be made, and that if you don’t make them yourself, and if you’re not on the same wavelength as the peple who are making them, it becomes a very painful experience, which it was. Obviously I directed the actors, composed the shots, and cut the film, so that, within the weakness of the story, I tried to do the best I could.