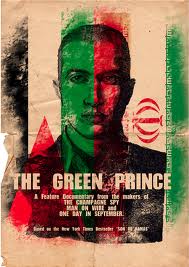

With all that’s going on in the world these days, I wasn’t enthusiastic about watching Nadav Schirman’s documentary, The Green Prince. It recounts and reconstructs the story of two men, Mosab Hassan Yousef and Gonen Ben Yitzhak. The first is the adult son of Hamas leader Sheikh Hassan Yousef. The second is the Israeli handler who turned Mosab into one of the most valuable informants his country has known.

With all that’s going on in the world these days, I wasn’t enthusiastic about watching Nadav Schirman’s documentary, The Green Prince. It recounts and reconstructs the story of two men, Mosab Hassan Yousef and Gonen Ben Yitzhak. The first is the adult son of Hamas leader Sheikh Hassan Yousef. The second is the Israeli handler who turned Mosab into one of the most valuable informants his country has known.

Watching this smart, tightly wound documentary, I felt challenged to put the current situation in the Middle East out of my mind. Then I failed to do so. This may demonstrate a flaw in the filmmaking, or — as in Errol Morris’ The Unknown Known — it may be a reflection of the way the world actually is.

Schirman, in The Green Prince, has found a story worth telling. He also tells it well, using recovered footage, interviews, and first-person narration to introduce us to a world we might hope to never inhabit. Mosab is a young Palestinian. His loving father works at the upper echelons of Hamas — an organization you doubtlessly have your own impressions of — and, as a result, spends a good deal of his time in Israeli prisons. Angry at the world that so crudely constricts his community, Mosab illegally buys a gun, then attempts to smuggle it back into Occupied Palestine, where he hopes to use it for mayhem.

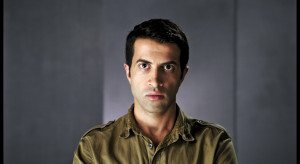

Being a teenager, Mosab does not realize that the Shin Bet — Israel’s secret service — will be watching him. He is arrested. One Shin Bet agent, Gonen Ben Yitzhak, uses indelicate means to ask Mosab to spy for Israel. Mosab agrees with no intention of following through. It is only after, in a prison run by Hamas, that he witnesses for himself just how indelicately people can ask questions, even — or especially — when those questions have no answers. Mosab, like a teenager, questions his father’s methods and morals. He becomes an Israeli spy, known, due to his extremely high level of access, as the Green Prince.

One half of this film is about the life of Mosab Hassan Yousef, son of a Hamas leader, betrayer of his people, inside-out savior assailant. He uses his privileged access to set up wanted men, to spare his father’s life, and to prevent act of terror. He does the kinds of things that his neighbors would kill him for, publicly. He does them because he feels they are correct.

And that is the other half of The Green Prince — the half that is not so much in the film, as in your head. Schirman follows Mosab as he loses the ability to persevere. He follows Gonen as he breaks rules to shelter Mosab and is subsequently excused from duty as handler. Mosab flees to America and extracts a complex ending from his insane story, one he publishes in a book on which this film is based.

You can watch The Green Prince and experience Mosab’s story. That is easy to do and worth your time. Less simple is to stand back from what’s being presented so that you might question it, indelicately. This is the true story of a young man convinced to betray intimate, cultural, familial trusts. It is the story of another man who takes his own risks to repay those favors. Seen from the eyes of Mosab and Gonen, one might call this story inspiring, or deem the ending happy.

Gonen and Mosab live in our world, though. We cannot extract them from what happened and what continues to happen. The Green Prince starts and ends with a story that has no clear beginning and which threatens to go on forever. Encapsulated as it is, the story fascinates and moves. Without its artificial wrapper, the gleaning goes on.

I watch The Green Prince and think, “Here are two men who have maintained their humanity in inhuman situations.” I do not see it and remember that all of the men and women within its frames are human in inhuman situations. That realization comes later.

I feel for Mosab Hassan Yousef. I feel for Gonen Ben Yitzhak. Watching this film, and the earlier documentary The Gatekeepers — about the men who led the Shin Bet, with which this would make an excellent double feature — I feel so many things for so many people. In that sense, The Green Prince is a complete success. The fact that I leave with no clear idea of how one might soothe the inhuman situations it presents as fait accompli makes the film less successful.

But the weight of the world can’t rest on one film. That weight’s too busy sitting on those of us who keep the world spinning.

I don’t know that your sense of being left hanging is a failure on the part of this film (I comment in the abstract–I haven’t seen it, though I now plan to). It may actually count as another of the film’s successes.

If you’d come away a freshly-turned bodhisattva, with the beginnings of an idea that would soothe and smooth the inhuman situation between Israel and Palestine (and everywhere; let’s face it, if you could unknot this Gordian tangle, you could cut through pretty much any human discord), would that have made the film a success? Gauging an artistic work’s success on its capacity to turn one into Christ or Buddha or (perhaps more appropriately) Douglas Adams’ Fenchurch, or to induce the delusion that one is any of the above, seems a pretty high standard.

(On the other hand, a production’s capacity to induce delusion may very well be a marker of success on a grand scale. I’m thinking of the original radio broadcast of Wells’ “War of the Worlds,” here.)

The kind of layered time-release of shattering realizations that you describe–empathy for the protagonists’ humanity; then for their enemies and allies’ humanity; then fear at the trap in which they all alike have caught themselves, abyssal and smooth-walled and inescapable–these sound like the product of the very highest art, a piece that recalls the likes of Dostoyevsky and Camus.

In fact, the final layer may be the film’s induction of a feeling of responsibility for these people, of a desire and need to resolve their tragedy–the viewer’s reach for the film, the nearest instrument to hand, and subsequent frustration at its inadequacy. That last, flailing grasp for purchase on the problem might very well be the best marker of it’s portrayal’s success.

I certainly remember feeling this way after reading Camus.

Or–and this is also possible–have I misunderstood your feelings?

! “…*its* portrayal’s…” Sorry. I do know the difference between a possessive and a contraction.

Or perhaps I expressed myself too obliquely.

The film feels unquestioning of the assumptions that Hamas deserves eradication and Israel deserves to protect itself in the way that it does. Neither is above question.

But I didn’t (and don’t) want to get into a morass of finger pointing in re: the Middle East. My own thoughts on the matter are complex and not of relevancy to this blog.

I just wanted to raise an eyebrow at a film that avoided a difficult question — one that sits at the center of its subject matter.

Ah. I did misunderstand then. But we agree; neither proposition is above question–and the film having avoided the question, while centering on a turncoat/spy in the Hamas organization, makes it far less insightful than I’d originally imagined.