Damien Chazelle, writer/director of Whiplash, patrols his hotel room in search of his shoes. I’m on the couch, wishing I had said yes to the offered cup of coffee. Might need a bit more verve; I can’t tell if I’m rushing or dragging.

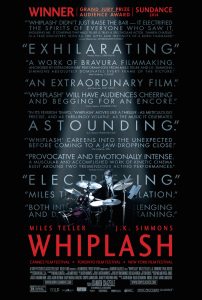

I’m here to interview a man who’s shot from student filmmaker to Sundance slayer in one clean stroke. Whiplash, if you haven’t seen the trailer, is a diabolical duet. Miles Teller plays Andrew, a first year student drummer at a top-rated music conservatory in Manhattan. J.K. Simmons is Terrence Fletcher, the director of the conservatory’s award-winning band. Fletcher brings the best out of his boys by grinding them into meat paste, throwing furniture at their heads, and spitting molten lead.

If they survive, well then, they’re great. If not, what does it matter? In Whiplash, Andrew thinks he can be great. He’s betting his life on it.

I can’t speak for Andrew’s chances, but I can say that both Miles Teller and J.K. Simmons — and for that matter, Whiplash itself — they’re great.

But hell if I’m going to sit down with Damien Chazelle the week his film opens and tell him, ‘Good job.’

(Some discussion of plot points ahead, but Whiplash is not a movie that depends upon surprise. It thrives on tension — which requires you to know what’s coming for full effect.)

Evil Genius: Whiplash is all about the fear of not achieving greatness. That resonating for you now?

Evil Genius: Whiplash is all about the fear of not achieving greatness. That resonating for you now?

Damien Chazelle: Yeah! (laughs) Fear is probably the easiest thing for me to make movies about because it’s what I feel on a daily basis. I’ve just sort of resigned myself to the fact that I’m a naturally anxious person.

EG: I can relate.

DC: In high school, all my fear got distilled into one person. Nothing else really scared me. It was purely this conductor who was my boogeyman, but who also gave me purpose.

The whole time I was drumming, I was thinking — it’s going to be so amazing when I’m out of high school and I don’t have this fear all the time. And then I went to college and half way through — typical of how the mind works — I started having panic attacks and that culminated in almost a nervous breakdown.

Looking back; it was clear that my mind needs something to be anxious about.

EG: This conductor; have you spoken to him about Whiplash?

DC: No. He actually passed away shortly after I graduated high school. I don’t know if he’d recognize himself in this… Okay. Yeah, he would. He definitely would.

Now, I almost feel bad that the conversation is based on this guy. I wrote Fletcher specifically as a villain; to be a monster.

EG: Really?

DC: My conductor wasn’t a monster. He was the best teacher I ever had. It was more like… he was controversial. He pushed people really hard. And he knew he terrified people and I think he enjoyed that power, but he used it to create the best high school jazz program of its kind in the country. It was this rare experiment with a public high school in New Jersey. We played presidential inaugurations and the JVC jazz festival and crazy stuff that public high schoolers just don’t get to do.

I have fond memories of those days, but I also remember feeling utterly terrified of this man every day. And I know I wasn’t the only one.

So there’s the question of what that does to your psyche? What does that do to you as a musician, when your relationship to the art form becomes one of rage and fear and stress and all these negative emotions.

EG: It’s interesting to hear you describe Fletcher as a villain. That’s not how I saw him. When the screening was over, my first thought was ‘torture porn love story.’ Andrew and Fletcher need each other. They love and hate each other.

DC: That’s a great way of putting it. Yeah, it is a love story at its core — a really twisted one.

EG: There’s something fascinating about the connection between our drive to greatness and the self-destructive nature of that drive.

DC: This is what I grapple with. How do you balance work and life? Filmmaking is a collaborative endeavor, at least. Drumming… you’re playing in an orchestra but there’s something very solitary about practicing your instrument in a room with no windows.

A lot of musicians seem aloof, but then they’ll play and you’ll hear emotion that you didn’t think that person was capable of. I find that kind of transference really interesting. It’s hard to save all your emotions for your instrument and still have a healthy personal life.

EG: Your first film, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, also revolves around the confluence of emotion and music, plus it sounds like your next film, La La Land, will as well. Do you think there’s something music can communicate that other mediums can’t?

DC: Music is so emotionally loaded. Nothing can tip a movie into cheesiness like a bad piece of music but also nothing can save a movie like a good piece of music. It’s such a powerful tool, like holding a weapon in your hand.

That means you have to handle it delicately but it also gives you a lot to dramatize.

EG: Whiplash seems a perfect title for this film. When in the process did you settle on that? It’s a Hank Levy piece, right?

DC: Yeah. The track Whiplash wasn’t written specifically for drummers — there’s no drum solo like in Caravan — but it’s a really hard piece for drummers to play. It switches time signatures in a weird way and even when it’s doing its normal time signature its adding beats, so it’s a really hard chart to get a handle on.

It was the first song they played in band, my first day in band. Just like in the movie: I remember seeing the chart and immediately being overwhelmed by it. Even before the movie was called Whiplash, that chart played a big part in the script.

Our original title was ‘The Drummer’, but then another movie used that name so we had to change it. Someone else suggested Whiplash. I resisted at first — it sounded too much like a horror movie, but then, that’s kind of right!

EG: It’s a self-inflicted horror movie! There’s a real self-destructive element here that made me think of Full Metal Jacket and Black Swan. In all three films, characters are destroying themself in order to achieve something more. Did films such as these inspire you?

DC: I saw Full Metal Jacket when I was in band and remember thinking that I had finally seen something that corresponded to what band felt like to me. Then Black Swan gave me flashbacks. I watched that in a state of heightened dread.

It’s funny: Black Swan is such a fantastical story, bordering on horror. It’s a “non-realistic” movie, but it felt more true to my personal experience as a musician than most “realistic movies.” That’s what it feels like to be a musician in a competitive climate. It feels like you’re in a war movie or a horror movie and you don’t know if you’re going to make it out alive or not. It’s a naturally over-the-top state of being because your emotions are constantly at 10 or 11 and you’re constantly vulnerable to attack.

That’s what it feels like. You’re living life at full pitch.

EG: So, there’s this line in the film, where Fletcher says, “There are no two words in the English language more harmful than ‘good job.’”

But then, in contrast, you’ve got one of my favorite scenes — a dinner party in which Andrew is craving acclaim and lashing out because he doesn’t receive it. Which side of that line do you fall down on? Do you want to hear praise, or is it harmful?

DC: It always feels like it helps, but I don’t know. Maybe in the long-term it hurts you. It’s really a difficult thing. I wish I could be the kind of person who could not care and shut himself off from the world, but I’m not. I find myself always immersed in reactions.

I don’t know how to juggle the making of the art with the taking of that art out into the world and wishing it well. I crave approval, but at the end of the day what I take home is not that. I fixate on the things that I could have done better.

EG: Does Whiplash have a happy ending?

EG: Does Whiplash have a happy ending?

DC: No. I think I’m even more pessimistic about the ending than everyone else. I wanted to end it with a kinetic rush and in a way that leaves you feeling pumped but the intent is for there to be a sour taste to Andrew returning to the fold of this abusive world.

It’s Fletcher getting yet another reason to think he’s doing the right thing.

EG: About that final act. How much of that is Fletcher with a plan and how much is showing Fletcher with fluctuating motivations?

DC: I wanted to leave it open to interpretation. It’s possible that J.K. had a different perception of it, but my perception is that Fletcher is never an asshole just to be an asshole. He’s an asshole with a motive. He stages the greatest humiliation for Andrew that he can think of. The whole movie is a series of humiliations. He’s trying to break Andrew down and he tries again and again and again but it doesn’t quite work. As much as Andrew is failing, Fletcher is failing.

Finally he goes for broke and puts his own conducting career — which he doesn’t give a shit about anyway — on the line to create this final, epic humiliation for Andrew, the humiliation that he really should not be able to climb back up from. And his hope is that he won’t have to think about this kid any more or that Andrew will rise from the ashes like Charlie Parker and in Fletcher’s words ‘play the best motherfucking solo the world has ever seen.’

I think he’s ready for both outcomes. I think the venom with which Andrew takes rein on stage surprises Fletcher. Certainly that’s how J.K. performs it.

That was the irony for me. End the film on a pair of smiles but it’s not a happy ending.

EG: Indeed. Thanks Damien. No offense, but ‘good job.’

Bonus Mini-Review

Watching Whiplash gave me the shakes. For over an hour afterwards, I walked around trembling — feeling percussed. Then I got home and immediately downloaded a Buddy Rich album. In the week since, I’ve been listening to more and more jazz drumming. I feel that’s as succinct a review as I can give the film.

Chazelle has pulled tangible intensity out of Teller and Simmons and imbued this straightforward tale with the sort of universal truth fiction requires to lock in. There are story moments that felt contrived, but on an emotional level, everything kept perfect time. I’m looking forward to watching it again.

When asked post interview, Chazelle recommended Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers for those of us seeking an Awesome Mix of jazz drumming. The album I’ve got on now is Moanin’.

Whiplash opens October 17 at the Landmark Clay Theater in San Francisco and October 24 at the Landmark Shattuck in Berkeley and at the Camera in San Jose.

Yep, this movie was an intense ride. And a damn good one. Interesting to hear Chazelle’s take on the ending. That’s one thing I couldn’t tell when watching it, whether or not from Chazelle’s point of view he approves of Fletcher or thinks he’s evil.

Indeed. I like that he left that ambiguity in the film, but was willing to offer his own opinions. I think he was genuinely traumatized by his conductor and still thought that he was an excellent teacher — so that’s the paradox and what makes Whiplash so engaging.

Are you happy when someone makes you miserably great? What do we want out of life?

And it’s important to remember that Andrew can step away at any time. Any abuse he takes is abuse he shows up to receive.

Chazelle also wrote this film I haven’t seen, Grand Piano, with Elijah Wood. It sounded a bit pulpy but perhaps I’ll check it out now.