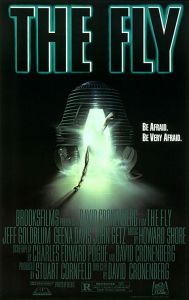

The Fly remains the most popular movie David Cronenberg has ever made. When released in ’86, it grossed more than all of his previous movies combined. Since then, nothing he’s directed has earned even half as much as The Fly. Which I point out not because I think box office is a measure of quality—I’ve loved Cronenberg since I watched him blow up a guy’s head when I was 10, I see everything he directs—but because The Fly is almost identical to the movies leading up to it, and to many that followed.

The Fly remains the most popular movie David Cronenberg has ever made. When released in ’86, it grossed more than all of his previous movies combined. Since then, nothing he’s directed has earned even half as much as The Fly. Which I point out not because I think box office is a measure of quality—I’ve loved Cronenberg since I watched him blow up a guy’s head when I was 10, I see everything he directs—but because The Fly is almost identical to the movies leading up to it, and to many that followed.

It’s the same insular story of self-aware body-horror, same small cast, same ominous exterior shots of futuristic buildings, same small rooms in which almost all the action is set, same profoundly disturbing gloopiness, same epically depressing ending. Yet people adored it. Critics too. Even the ones who hated horror movies, who hated Videodrome, who hated Cronenberg. Why?

Not because of any of the above. People love The Fly because it’s a well told tragic love story that ends in death. It’s that simple. The Fly is Cronenberg’s Titanic. By which I mean the movie, not the doomed oceanliner.

(Which as an aside, it’s funny how that expression is now cause for confusion. Pre-James Cameron, someone’s Titanic was their downfall, their hubris come back to bite them, to death, probably. But now? Now someone’s Titanic is their most massive success, i.e. the polar opposite of its prior meaning. And in Cronenberg’s specific case, it’s his biggest success and his tragic love story. Huh. Language is fascinating, ain’t it? Sorry, back to The Fly…)

So one of the lovers turns into a giant, goopy, monstrous fly, so what? She loves that damn fly! To the end, too. Not for a second does Veronica (Geena Davis) stop loving or caring for one-time sexy nerd scientist Seth (Jeff Goldblum). Sure, she’s scared of him by the end. But not so scared she’s uncool with his crashing through the glass wall of an operating room, scooping her into his weird bubbling arms, and carrying her to the top of his building to chat about the fate of their unborn, possibly mutant child. Even at the end, when he’s become a giant flybeast fused with the door of a telepod, she can barely bring herself to shoot him. That’s love, people, the kind you only wished you ever felt.

Cronenberg describes it thus:

To me the film is a metaphor for ageing, a compression of any love affair that goes to the end of one of the lover’s lives. I can be a sucker for a romantic story, believe it or not. I’m not totally cynical. Nor do I think I’m pessimistic. But the reality is undeniable, especially if you don’t believe in the afterlife—where you walk hand in hand through the clouds together. Every love story must end tragically. One of the lovers dies, or both of them die together. That‘s tragic. It’s the end.

Whether or not viewers would put it this way themselves, this is exactly what the film taps into. It couldn’t be any simpler. It may be Cronenberg’s most streamlined movie.

It begins at some kind of cocktail party for scientists. Seth tells Veronica he’s working on a project that will change the world and invites her to his place to see it. She declines, walks away, he runs up to her, says no, seriously, I’m changing the world, come with me. She says yes. This takes maybe two minutes. And hey presto, they’re at his loft and he’s teleporting her stocking. I love a movie that doesn’t mess around with needless backstory. So many extras hired for this scene! And for two minutes of screen time.

Cronenberg’s prior movies move with a similar directness, but none have a love story as their focus. Scanners is about warring brothers, The Brood about a broken marriage, The Dead Zone about a loner, Videodrome about stomach vaginas. Following The Fly, Dead Ringers is about twin vagina enthusiasts, and Naked Lunch is about talking assholes on dope. So you can begin to see why The Fly hit the popular zeitgeist in a way the others didn’t.

So what goes wrong? Why does Seth turn into a fly? Early on, he puts a baboon in the teleporter, even though he knows it (the teleporter) has issues with the animate. Which is, frankly, a ghastly move no one in the movie addresses. Why not a rat, Seth? Or a cockroach? He turns the baboon inside out.

Granted, Seth’s put out by the failure, but still. Maybe you could have used, say, a guinea pig? Literally? He rants about not understanding THE FLESH as well as he must, a blatant shoe-horning into the film of Cronenberg’s favorite thematic element, prominently featured in Videodrome—long live the new flesh!—inspired by Cronenberg’s love of author J.G. Ballard, noted for his peculiar, fetishistic joining of flesh and technology, most famously in his novel Crash (later adapted by Cronenberg), though more effectively (or at least entertainingly (according to me)) in an earlier novel, The Atrocity Exhibition (which if you’d like an intro to this angle of Ballard’s work, you should read).

The flesh, thematically speaking, doesn’t play much of a role in The Fly outside of this one brief rant. The following scene, naturally, is the one where Seth and Veronica have sex for the first time. Having learned about the flesh (was Seth a virgin? Thematically, yes), Seth rushes to his computer and types, teaching it what he’s learned (is he typing Shakespearean sonnets into it? How do you teach a computer about the flesh?). Next thing we know, he’s teleporting the baboon’s brother successfully.

It’ll be weeks before tests on the baboon come back to verify its health. But as luck would have it, Veronica leaves to deal with her old boyfriend and editor, Stathis Boran, leaving Seth to brood and get drunk and say fuck it, the baboon’s fine, I’m going through. He teleports himself out of drunken, baseless jealousy. We’ve all been there. Who doesn’t relate to Seth in this scene? Lucky for the rest of us, we didn’t have a pair of telepods handy.

A fly gets into the telepod with him, and there we are. Fly and Seth are merged into Brundlefly.

Which is a shame, because one element of the movie never again dealt with is that TELEPORTATION WORKS. Minus the fly, Seth just changed the world. And no one cares. But again, this is not a movie about teleportation. It’s a tragic love story. Every other element exists only to further the tragedy.

At first Seth is a new man. Strong and excitable and a fiend for sugar. But not for long. Soon he sprouts dubious hairs, yells at Veronica, and trolls seedy arm-wrestling bars for whores, one of whom he brings home. He tries to get her into the teleporter, but does so with all the finesse of a nerdy scientist.

Veronica walks in on them, and still she won’t give up on Seth. Not even after he goes gloopy. Before watching The Fly recently, I hadn’t seen it for at least fifteen years (though I must have watched it about 947 times in my teens). I forgot just how unsettling the gloopy bits are, the nails coming off, the regurgitation. It’s a nasty business, this metaphorical ageing. But as Cronenberg points out, “It was never just gloop; it was always conceptual gloop.” Exactly right.

I’d also never before seen the excised “monkeycat” scene, one Cronenberg removed after test screenings (and which is now included on the blu-ray, or watchable on the youtubes). In it, Seth, far along in his transformation, tests his gene-splicing concept by joining a cat and the other baboon. The result is a deformed, screaming beast that leaps on his face. Seth beats it to death with a pipe, runs to his roof and screams. Which is when a giant fly leg pushes its way out of his abdomen. Alarmed by this new development, he breaks the leg in half, then bites it off.

Test audiences were disturbed by this sequence? Go figure. Apparently they felt it made Seth less likeable. This is terribly important. No matter how ghastly he becomes, we the audience are with Veronica all the way: we love the poor bastard. This is why The Fly works.

Cronenberg is right. The Fly is a metaphor, and not just the kind we can talk about as theme. It’s the kind the audience feels. Seth and Veronica are young lovers one of whom is beset by a terrible malady. Does she abandon him? Not for a second. She stands by him to the bitter end. Would we do the same? It doesn’t matter. The beauty of fiction is that it allows us to live vicariously the life of the faithful lover.

Cronenberg shot alternate codas, all involving Veronica dreaming of giving birth to a beautiful butterfly, some with her alone, some with her married to Stathis. None of them played. The story ends when she shoots the flypodbeast. Fade to black. The end. It’s devastating. No happy coda is needed. All it would do is undercut what came before.

Much as movie studio execs would have us believe audiences want happy endings, it’s simply not true in every case. Romances—counterintuitively?—work wonderfully as tragedies (I feel like Shakespeare had something to say about this), and for exactly the reason Cronenberg gives: the greatest, most loving, most perfect relationship in the world is still going to end with one—or both—lovers dying. How they deal with it makes for great drama.

What’s most impressive about The Fly, and this gets us back to where I began, with its striking similarities to every Cronenberg movie that precedes it, is that despite it being his most accessible film, it’s not in any way a softening of his aesthetic. It’s pure Cronenberg through and through. The gloopy elements are some of the most disturbing he’s ever put on film, but in the context of the tragedy, people otherwise turned off by horror accept it. Not even his recent, non-gloopy movies have met with the succes of The Fly. So I guess the lesson here is: people want someone to love, even if that someone is a giant bug. Make of that what you will.

Can you please, in this thread, rate all the cronenberg movies from gloopiest to least gloopy?

For you? Yes. Beginning with the gloopiest gloopers:

Shivers (AKA They Came From Within)

Videodrome

The Fly

Scanners

Naked Lunch

eXistenZ

Rabid

The Brood

Dead Ringers

A History of Violence

Crash

and then continuing with the non-gloopers in order of implied gloop perception, a tricky, subjective metric if ever there was one:

The Dead Zone

Eastern Promises

Fast Company

M. Butterfly

Cosmopolis

A Dangerous Method

I only saw Shivers once, about a decade ago, but it didn’t strike me as remarkably gloopy (by Cronenberg standards). I’m sure it deserves a high place on the list, but I don’t think anything is gloopier than Videodrome. I might also put Scanners below Naked Lunch and eXistenZ. Scanners has two remarkably gloopy (and all around great) scenes–one at the beginning, the other at the end–but that’s really it, isn’t it? Am I forgetting some significant gloop in the middle? In contrast, Naked Lunch and eXistenZ feel pretty gloopy throughout, as I recall. Also, where’s the gloop in Crash? Rosanna Arquette’s scar? Not sure I’d call that gloop, but okay, I won’t make a fuss.

Oh, and you forgot Spider. No gloop.

By the way, very nice article on The Fly!

Why thank you. I admit I may have written my gloop ratings hastily, possibly with the unconscious intent of inspiring vitriolic argument.

I, too, haven’t seen Shivers in many years, so maybe I was recalling subject matter–giant leechlike venereal disease monsters crawling into and out of people–more than actual amount of on-screen gloop.

Don’t know how I missed Spider. I love that weird little movie.