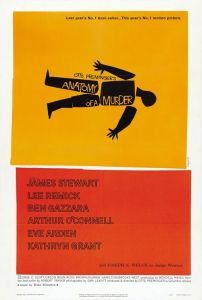

Anatomy of A Murder (’59) is far more demented, twisted, and evil than anyone gives it credit for. It’s given credit all the time for being one of the most realistic courtroom dramas ever filmed, for being morally ambiguous, for not providing easy answers, for the quality of its performances, for its black and white cinematography that borders on the noirish, for its Duke Ellington soundtrack, for its Saul Bass opening credits, and for director Otto Preminger’s non-showy, straightforward syle. As well it should be. But above all, Anatomy of A Murder is about people whose personal interests trump all else, primarily truth and justice.

Nobody in this movie is clean. They’re morally monstrous, every one.

Let’s start with the accused, Lt. Frederick Manion (Ben Gazzara). The story is that a bar owner, Barney Quill, drove home Manion’s drunken trollop of a wife, Laura (Lee Remick), but stopped off to beat and rape her. When she stumbled into her trailer and told Manion, he went to the bar with a gun and shot Quill dead. His defense, which he comes up with only after his attorney, Paul Biegler (James Stewart), spells it out for him (which we’ll be getting to), is to claim temporary insanity. Even though, as is obvious from the get-go, he fully intended to kill Quill, remembers it all just fine, and is going with the insanity plea because he’s been told it’s the only way to beat the system.

During the trial and the events surrounding it, we begin to understand a little more. Manion is violently jealous, attacking anyone who so much as flirts with Laura, and beating Laura herself. Laura is a drunk who regularly goes out nights when Manion is asleep.

By the end of the movie, one realizes that she may well not have been raped. She and Quill might have been having an affair, and learning of it, Manion might have beaten her, hence her injuries seen at the outset of the film.

But what we know for certain is that Manion was not temporarily insane. He was angry, either at an affair or a rape we don’t know, so he murdered Quill. Not exactly the standard sympathetic defendant in a courtroom drama. I kept expecting a twist to crop up at the end to further shed light on what happened or take the movie in a new direction.

No twist comes. The trial is not presented with the standard dramatic tricks we’re used to in movies, then or now. It endeavors rather to show how the process of a trial unfolds in as realistic a manner as possible.

Attorney Paul Biegler is the protagonist. We meet him after a fishing trip. He lost the job of D.A. to someone else, and hasn’t been practicing law since. Instead he sits around drinking whiskey and talking case law with elderly ex-attorney and alcoholic Parnell McCarthy (Arthur O’Connell). Out of the blue he’s phoned by Laura, begging him to take the case. Biegler knows nothing about the murder, but McCarthy does, and tells him to take it. Seems someone recommended Biegler to Laura, but who is never revealed. Did that someone know Biegler needed the attention of a big trial as much as Manion needed a lawyer? One Manion could get away without paying until he was freed?

Biegler hears out Manion as to the murder, then, on the advice of McCarthy, leads Manion to the realization that pleading insanity is his only hope. Now, Biegler doesn’t actually put the words in Manion’s mouth, but he holds his hand all the way there, until Manion figures out what he’s supposed to say.

Of course everyone should have a lawyer on their side, arguing their case, however specious that case may be. But in a movie, certainly a movie about a lawyer, our hero usually has some kind of virtuous side preventing him from freeing the killer, or at the very least being conflicted about it. They usually defend the accused killer knowing he’s innocent, or in more nuanced versions, not knowing one way or the other. Or else he thinks he knows, then finds out he’s been scammed.

Biegler knows Manion’s lying. He essentially told him to. Why? Because Biegler needs to win a big, attention-getting case. And this is it.

What’s more interesting still is the way Stewart plays him. He’s tough, he’s no softie, but he’s always a good guy. He’s very much the hero of the piece. In the courtroom, he’s all folksy language, bemusement, and outrage. He constantly asks inappropriate questions and calls out the prosecution for misconduct, even though he knows they’ll rightly object. The judge is ever telling the jurors to strike from their minds what they’ve just heard, something Biegler knows full well is impossible.

And of course, the way the movie is made, we’re rooting for him all the way, with every outburst and obviously leading question. He’s the hero! We want him to win. He never says outright that he’s taking the case for the fame. He just needs to get paid, he says jokingly time and again, and anyway Manion can’t pay him until he’s out. It’s set up that Biegler is doing the accused a favor, because…well, again, it’s never stated outright. Biegler needs this, and once Manion agrees to claim insanity—a plea Biegler knows might work—Biegler’s in.

Knowing Manion’s guilty of murder, knowing Laura is a lush and a flirt and probably lying about something, Biegler nevertheless does all he can to win the case. And he does win. And Manion and Laura skip town immediately after, leaving Biegler unpaid. But he’s in a great mood anyway. He’s going to start up his practice again, with McCarthy as his partner. It’s played as a happy ending.

Is it? It struck me as monstrous. Which I assume is the point. Which is great! I love dark, monstrous movies. I just wasn’t expecting it from Anatomy of A Murder. I remembered it being surprisingly blunt in its talk of rape and adultery, but not in the way it showed the corruption built into the system. Or is the system corrupt? Should we just be happy a lawyer took a case and did everything he could to win it? Even encourage his client to lie?

At the end, I felt like Preminger had hoodwinked me. He’d made me root for Biegler, when I should have been rooting for the smarmy D.A. and the big city trial lawyer assisting him (played with the utmost in smarm by George C. Scott). At least the prosecution has the truth on their side, though their scheming methods are no more noble than Biegler’s. Or is truth not what to root for? Is the best case all we should be concerned with? That’s a stickier wicket than I’m going to discuss here, what with the dodgy nature of “truth.”

But so anyway, the point is, Anatomy of A Murder is one dark and wicked movie. Watch it if you want to feel filthcovered and violated.

Thank you for this brilliant piece on one of my favorite films. Saw it when I was in jr. High. It wasn’t until I was an adult and saw it again, that I understood the depths of this movie. Not at all a happy ending. Nobody wins.

You are very welcome. It is indeed all about depth. Watch it on the surface, and see a courtroom drama with a heroic lawyer. Start to dig, and things get dark in a hurry.

What was the purpose of the dog show in the court?

Diogenes searching for an honest man?

I thought it was going to lead to something but I think it was just for cuteness and to show what a great guy Stewart is

Quill’s daughter brought the missing panties to court because she believed that they were evidence that a rape did in fact occur. If they were not evidence of rape, why were they ripped and why were they taken by Quill from where the alledged rape took place? He probably planned on disposing them later when he had more time. But his higher priority at the time he threw them in the laundry shoot was changing his clothes…another telling sign of guilt. Also, if the sexual encounter was part of an ongoing affair, why did Quill have his bartender sitting lookout at the window?