Nothing about Big Eyes, the true story of artist Margaret Keane and her lying husband, is at all believeable, and that’s not a compliment. When every moment of your “based on a true story” movie rings false, you’re in deep trouble.

Nothing about Big Eyes, the true story of artist Margaret Keane and her lying husband, is at all believeable, and that’s not a compliment. When every moment of your “based on a true story” movie rings false, you’re in deep trouble.

Writing duo Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski and director Tim Burton have fashioned a movie totally divorced from this earth, which is a damn shame. Their last collaboration resulted in one of Burton’s very best movies, the criminally underseen Ed Wood (’94).

Alexander and Karaszewski have made a career out of writing movies about outsiders and weirdos. The biggest problem of Big Eyes is their decision to focus on Margaret Keane (Amy Adams) rather than her husband. Yes, she’s the artist. But she’s also, for almost the entire movie, a doormat on the sidelines of her own life, while her husband, Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz), wheels and deals and lies and schemes and becomes famous. In one sense, sure, it’s a shame to celebrate the liars and manipulators of the world, but let’s face it: they’re the interesting ones.

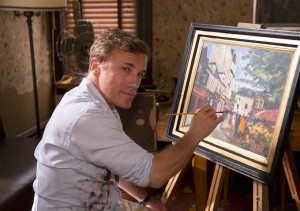

So Walter Keane is the fascinating personality of the movie, but he’s not the focal character. We learn nothing about him. The way Waltz plays him, he’s all surface. Mugging and smiling and scamming, or, in private family moments, raging in anger. A man desperate to be an artist who fulfills himself by stealing the work of his wife, who becomes rich and famous, a talk show regular, who even after his ruse is revealed lives his life insisting he’s the true painter, wronged by his insane wife? Sounds like an interesting movie. Too bad it’s not this one.

The focal character in this movie is Margaret, who does nothing but quietly seethe. And I mean literally, in every single scene, she does nothing but seethe. Quietly. Sadly. She’s sad and seething, and that’s her entire character. She’s given nothing else to do. Only at the end does she assert herself, and yes, that’s nice, but it’s too little too late. She’s as depthless as Walter.

It’s amazing the writers didn’t notice the passivity of their lead in advance. We need to get inside the head of such a character, we need to somehow be taken on their journey, instead of merely traveling alongside them as they go on someone else’s. Big Eyes is a total failure of character.

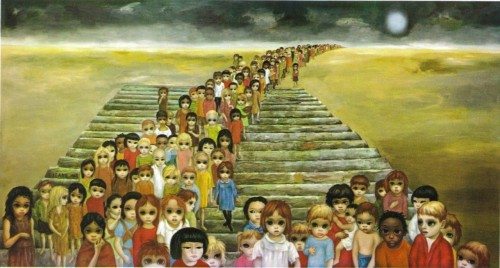

Also frustrating is the movie’s failure to take on the other issue at its heart: what is art? The most compelling moments of the movie are when Terence Stamp shows up as art critic John Canaday and articulately trashes Margaret’s kitschy paintings. Are they kitsch? Are they art? Just what is art? Who gets to decide? Does the term “art” even mean anything?

All questions we might hope a movie about Margaret Keane’s absurd big eyed children would address. Big Eyes addresses none of them. A few asides about the art world are tossed off by the likes of Jason Schwartzman as a snooty art dealer, and that’s it.

The climax takes place in a courtroom. Margaret, having finally, thanks to becoming a Jehovah’s Witness (hmm, that’s interesting, how about talking a little about—oh, nevermind), claimed to be the artist behind the big eyes paintings, takes Walter to court for a variety of reasons. The courtroom scene (for which surely there must be transcripts?) is possibly the single worst courtroom scene I’ve ever seen. The trial in The Kentucky Fried Movie is more plausible than this one. And a hell of a lot funnier.

Aside from being boring and implausible, nothing hangs in the balance in this trial. There is nothing to be revealed. No evidence, no witnesses, nothing. It’s just the vehicle through which Margaret may prove who painted her paintings. We know she painted them. She knows she painted them. Walter knows she painted them. It’s just a matter of going through the paces with some baffling mugging by Waltz providing, in theory only, the laughs.

Burton shoots the movie with garish, cloying colors, going one presumes for a look akin to magazines of the era. It creates an atmosphere slightly cartoonish. The acting and thin characterizations also tend toward the cartoony. It’s not a movie one is meant to take seriously. Why, I don’t know. Seems like rather serious business going on.

A final question never addressed–how could it be with characters of no depth?–is what it means that without Walter, Margaret Keane would never have found fame and fortune? It’s solely Walter’s doing that Margaret’s paintings took off. He was a master salesman. Liars and charlatans often are. Obviously the best case would have been for him to have pushed the paintings as Margaret’s. But he didn’t do that. He did what he did. Margaret endured something terrible, but it resulted in her becoming a famous artist. I wonder how that makes her feel? Someone oughtta make a movie about it.

Go to “Bigeyesmovie.com”, a site created by Walter Keane’s older daughter, for a far more plausible account of Keane’s career, and an interesting exploration of the issue of who painted what.