The new documentary Point and Shoot is recursive, reflexive, and a bit wrong. I do not trust it—not because it feels fabricated in the slightest—but because it makes me wary.

The new documentary Point and Shoot is recursive, reflexive, and a bit wrong. I do not trust it—not because it feels fabricated in the slightest—but because it makes me wary.

I do not trust Point and Shoot in the way you do not trust someone who stares for hours at your midsection, and then feigns only a fascination with your belt buckle. Although I suppose what I’m really saying is that I do not trust the film’s subject, Matt VanDyke, because he does not appear to trust himself.

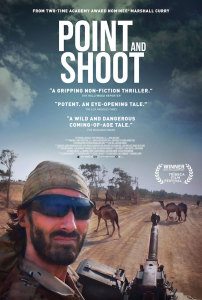

Directed by Marshall Curry, Point and Shoot relates the extremely odd story of a young man from Baltimore who, struggling with OCD and a cocoon of protective privilege, sets off to become a Hollywood-style action hero. You know, one of those men who doesn’t really exist.

His is a boyhood dream enacted by a man, maybe.

VanDyke is an odd duck, that’s for sure. Somehow he has the money to buy a motorcycle and ship it, and himself, to Africa, so that he might film himself riding around the Arab world doing wheelies.

As he travels, VanDyke learns and grows, but he mostly grows insanely brazen. He hangs about with soldiers in Afghanistan. He motors around Iraq alone. He remakes himself into a caricature of manliness, changing his name to Max Power or something equally ridiculous which I cannot quite remember. He gets punched in the face by policemen, and buys guns, and continues to panic if he believes he’s been touched by the corrupting influence of sugar—part of his OCD—or if he goes over a bump on his motorcycle — what if that was a human he’s run over without noticing?

Better go back and check the helmet cam footage.

The first half of Point and Shoot follows the transformation of Matt from sheltered, obsessive, and fearful to sheltered, obsessive, and fearful but all that hidden under a veneer of dubious machismo. Then he meets some Libyans, who invite him to Libya. He bribes his way into the country and there, amazingly, finds himself.

The first half of Point and Shoot follows the transformation of Matt from sheltered, obsessive, and fearful to sheltered, obsessive, and fearful but all that hidden under a veneer of dubious machismo. Then he meets some Libyans, who invite him to Libya. He bribes his way into the country and there, amazingly, finds himself.

After all his derring-do and ill-fitting manliness, Matt VanDyke makes friends. He isn’t firing sawn-off shotguns; he’s laughing and caring. He goes home to his girlfriend a changed man — not because he’s done or seen or recorded (and he’s recorded most everything) — but because he’s identified himself in the swirling noise of the world. If you’ve traveled like Matt has, maybe you can relate.

He wants to be one thing, and he acts that part on camera, but he cannot deny who he is. Discovering himself, his trip is successful and over.

Then the Arab Spring takes hold in Libya. In less than a day, Matt tells his girlfriend and mother goodbye and jumps a plane to Cairo. He races back to Libya. He feels he must help his friends by becoming, alongside them, an armed revolutionary. This is what men do.

And that’s why I don’t trust Point and Shoot and Matt VanDyke. VanDyke is clearly fixated on how he appears on camera; that’s the subtext of the entire film: if you pose a certain way, are broadcast doing certain things, then you are such a person. This is the nature of media and celebrity and human idiocy.

And that’s why I don’t trust Point and Shoot and Matt VanDyke. VanDyke is clearly fixated on how he appears on camera; that’s the subtext of the entire film: if you pose a certain way, are broadcast doing certain things, then you are such a person. This is the nature of media and celebrity and human idiocy.

For its part, Point and Shoot wields its own illusory power over its subject, certainly aware of its corrupting effect. Matt wants to be seen a certain way; here is an entire documentary about him behaving a certain way. It does not fabricate what does not exist, or shy from his OCD oddness, but it does feel manipulative of this human being — Matt thinks he’s telling his story, but his story ends up being about how telling your story is essentially dishonest.

Considering these insights in light of the nutsy-cuckoo things Matt VanDyke does isn’t a bad way to spend an hour and a half. If you’ve got a rambunctious teen who likes to play bang-bang, this tale might open their eyes, as long as it doesn’t go over their head.

Alas, it appears to have gone over Matt’s head. And that is also why I feel a bit dubious of Point and Shoot. Matt VanDyke isn’t a bad guy; he’s just an odd duck. He does what he does out of misplaced enthusiasm and media-fed dreams and misconceptions of manhood. His heart is good even if I’m unimpressed by his thinking.

I can’t help but feel the film holds him up as a fool.

A brave fool, but a fool.

By the time Point and Shoot closes, Matt VanDyke has fought his rebellion, faced death, and done what he can to become a man. If I had the chance to meet him, I’d tell him that he’d more than achieved his aims halfway through.

All that stuff with guns — that’s not manhood, that’s just the military.