Martin Luther King Jr. doesn’t know beans. That’s what Ava DuVernay’s drama about the notable Civil Rights Movement march, Selma, suggests — and that’s why the film is better than 98% of most others of its kind.

Martin Luther King Jr. doesn’t know beans. That’s what Ava DuVernay’s drama about the notable Civil Rights Movement march, Selma, suggests — and that’s why the film is better than 98% of most others of its kind.

If you’ve been reading Stand By For Mind Control for any length of time, you’ll know I’m not a huge fan of biopics. Generally these treacly tales cram their subject’s life story into a handful of clunky, exaggerated, and stupid beats. Each exalted hero is formed in a dramatic gestational incident. Early success gives way to struggles with narcotics, or alcohol, or infidelity. Then, phoenix-like, the real-life protagonist overcomes and celebrates at the Oscars or the Grammys or, not frequently enough, at Roscoes.

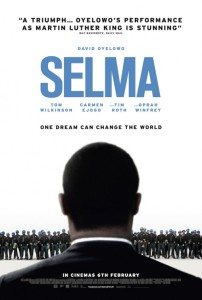

Selma is not this sort of biopic. To begin with, Paul Webb’s script doesn’t bother with a whiff of backstory for Martin Luther King, Jr. He launches the tale as Dr. King (David Oyelowo) and his wife, Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo) dress up for an evening out. King laments how phony he looks in high-falutin duds and dreams of one day being a small-town preacher, of owning their own house. If this film were 42: The Jackie Robinson Story, luck, perseverance, and talent would lead King to the ends of which he dreams.

Selma is not this sort of biopic. To begin with, Paul Webb’s script doesn’t bother with a whiff of backstory for Martin Luther King, Jr. He launches the tale as Dr. King (David Oyelowo) and his wife, Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo) dress up for an evening out. King laments how phony he looks in high-falutin duds and dreams of one day being a small-town preacher, of owning their own house. If this film were 42: The Jackie Robinson Story, luck, perseverance, and talent would lead King to the ends of which he dreams.

Selma isn’t that movie. King is getting dressed to accept the Nobel Peace Prize. That’s how the film starts: with a man at the peak of his power, but dreaming of a life as free of conflict as yours. He has a dream, yes, but it’s of being unburdened. Of being able to call it a day.

Most likely, you have some sense of what happens (and with some accuracy, happened) in Selma. Dr. King and his associates repeatedly attempt to march to secure voting rights for blacks in Alabama — rights they are entitled to by Federal law. They face violent resistance from the local police and populace and receive either lackluster support from Federal authorities like Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) or outright hostility, such as they receive from J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker).

Most likely, you have some sense of what happens (and with some accuracy, happened) in Selma. Dr. King and his associates repeatedly attempt to march to secure voting rights for blacks in Alabama — rights they are entitled to by Federal law. They face violent resistance from the local police and populace and receive either lackluster support from Federal authorities like Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) or outright hostility, such as they receive from J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker).

Those two being, in order, the President of the United States and the Director of the F.B.I, in case you’re behind on your American history or haven’t reached that chapter in your social studies textbook yet.

Today it was announced that Selma was nominated by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences for a Best Picture Oscar. That’s a shame, as it really should have been nominated for Best Actor — David Oyewolo — who brings stunning humanity and depth to a man who is more often seen carved in stone, and also a Best Director award for Ava DeVernay. Selma is not the best picture of the year, but Oyewolo may have given us our finest lead performance, after Jake Gyllenhaal’s in Nightcrawler, also un-nominated. DeVernay wouldn’t win Best Director (that should be Richard Linklater), but her powerful work here deserves recognition.

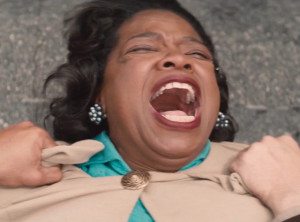

It is no easy feat to stylishly recreate iconic moments without sacrificing pathos, but that’s what she does. When young Jimmie Lee Jackson (Keith Stanfield) is shot by Alabama State Troopers, you will cry alongside his mother. When Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey) is, struggling, taken to the ground by police, you will, from your seat, lend her your own power so she can persevere. When the marchers — men, women, children — cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge to face the clubs, whips, and fists of uniformed men, DeVernay’s direction puts you there among them in the smoke and blood and pain.

It is no easy feat to stylishly recreate iconic moments without sacrificing pathos, but that’s what she does. When young Jimmie Lee Jackson (Keith Stanfield) is shot by Alabama State Troopers, you will cry alongside his mother. When Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey) is, struggling, taken to the ground by police, you will, from your seat, lend her your own power so she can persevere. When the marchers — men, women, children — cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge to face the clubs, whips, and fists of uniformed men, DeVernay’s direction puts you there among them in the smoke and blood and pain.

You will feel bludgeoned and dazed, and so you should. You, like Dr. King, will have second thoughts. You will wonder whether there is victory to be won or just suffering to be endured. Only time will tell.

This film, Selma, is historical recreation. It is no spoiler to tell you that LBJ comes around, that the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee triumph in the courts and indeed march to Montgomery, paving the way for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It also not a spoiler to tell you that despite all the progress Dr. King and those like him fought and died for, Selma doesn’t quite have a happy ending. There is, so far, no end in sight.

This film, Selma, is historical recreation. It is no spoiler to tell you that LBJ comes around, that the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee triumph in the courts and indeed march to Montgomery, paving the way for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It also not a spoiler to tell you that despite all the progress Dr. King and those like him fought and died for, Selma doesn’t quite have a happy ending. There is, so far, no end in sight.

Selma is not a film of inspiration, struggle, and victory; it is a film of burdens and conflict, and of burdens and conflict that continue, despite hard-won progress.

Selma ends with Oyewolo’s Martin Luther King Jr. addressing the crowds in Montgomery (not with King’s actual speech, mind, to which Dreamworks holds the rights, shudderingly), but I did not glory in victory. I thought about America today, and about how people protest today, and about how much simply fails to congeal without leaders like MLK.

Those being leaders who stand up not because they aspire to power, or to glory, but in spite of their distaste for it. True leadership is about sacrifice. Real heroes don’t succeed; they suffer on. That’s what Ava DuVernay’s film teaches. That’s what David Oyewolo’s performance reveals. Our heroes are real people with real flaws. The gulf between them and us exists only in our perceptions.

Those being leaders who stand up not because they aspire to power, or to glory, but in spite of their distaste for it. True leadership is about sacrifice. Real heroes don’t succeed; they suffer on. That’s what Ava DuVernay’s film teaches. That’s what David Oyewolo’s performance reveals. Our heroes are real people with real flaws. The gulf between them and us exists only in our perceptions.

In this way Selma reminds me of Steven Soderbergh’s two-part film Che, about the life of Che Guevara. That film arrays the events that brought about the Cuban revolution under Guevara’s leadership. Soderbergh’s ambitious experiment does not set out to glorify Che. He sets out to humanize him. At this he succeeds, revealing the icon’s everyday humanity.

You could be Che, the film suggests, if you tried. You could be Martin Luther King Jr. too, Selma intimates, if you are willing to suffer. You aren’t guaranteed to be as well-regarded as either man, but there is nothing you need to set forth save the spirit and the opportunity.

And if you care about how you’ll be regarded, you’re starting off on the wrong foot.