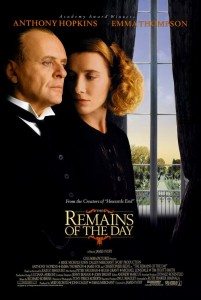

I remembered The Remains of The Day, the movie, which I saw once, when it opened back in ’93, as being a powerful, subtle, beautifully acted, emotionally subdued tale of an aging butler’s wasted life. I remember liking it a lot. I think I never read the book because how different could it be? It’s a small, highly contained story about a butler. Surely, I imagined, if any movie captured the essence of its source material, it must be this stately Merchant-Ivory production.

I remembered The Remains of The Day, the movie, which I saw once, when it opened back in ’93, as being a powerful, subtle, beautifully acted, emotionally subdued tale of an aging butler’s wasted life. I remember liking it a lot. I think I never read the book because how different could it be? It’s a small, highly contained story about a butler. Surely, I imagined, if any movie captured the essence of its source material, it must be this stately Merchant-Ivory production.

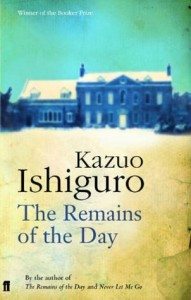

I read many other Ishiguro novels over the years (The Unconsoled is the weirdest and best; highly recommended to any serious readers out there) and always loved his writing if not the stories (Never Let Me Go didn’t click for me the way it did for many, the movie version even less so), yet the one many claimed was his masterpiece I never got around to.

Until I did. I read The Remains of The Day recently, and holy hell is that a powerful novel. Subdued in the extreme, but ultimately as sad as anything I’ve ever read. It’s narrated by Stevens, the butler, in his carefully controlled voice. He allows little emotion to affect him. But what emotion creeps in reveals a great gulf of barely acknowledged grief.

Until I did. I read The Remains of The Day recently, and holy hell is that a powerful novel. Subdued in the extreme, but ultimately as sad as anything I’ve ever read. It’s narrated by Stevens, the butler, in his carefully controlled voice. He allows little emotion to affect him. But what emotion creeps in reveals a great gulf of barely acknowledged grief.

When the story begins in the mid ‘50s, Stevens’s longtime employer, Lord Darlington, has been dead some years, his mansion bought by an American. Stevens stays on–a part of the package–with a staff of only four working under him. Not like the old days, in the years between the two great wars, when Darlington Hall saw world leaders and other men of great political influence meeting under its roof to decide the fate of the world.

Stevens receives a letter from one-time Darlington Hall housekeeper, Miss Kenton, implying, or so Stevens wishes to infer, that her marriage is ending and that she might like to return to her old job. So, offered use of the fancy old Ford by his American employer, Stevens takes a rare trip from the Hall to visit Miss Kenton.

Now, Stevens isn’t about to admit to we the readers that he ever loved Miss Kenton and wished it was he who’d married her, nor that his trip is being taken in the hope of starting a late-in-life romance. He’s not about to admit it to himself, either. But we come to understand that this is what’s driving him, even if he never does, not fully, not in a way he’s willing to consciously acknowledge. He’s tightly wound, Stevens is.

During his trip, he relates stories of his past experiences as Darlington Hall, those with Miss Kenton, and those concerning Lord Darlington’s efforts to maintain a post-WWI peace by making nice with the Germans. Most of all, Stevens ponders what it means to be a truly great butler. A great butler, he concludes, may be defined by his dignity. Dignity. What is dignity? It is being cool under pressure. It is being a butler, from the inside out. A great butler doesn’t see butlering (butlery?) as a job. It is a state of being. The only a time a great butler may allow what’s inside of himself to come out is when he’s alone. In the presence of others, he must maintain absolute control.

Furthermore, a great butler must devote himself to a great house. And once devoted, he must not ever sway in his devotion.

As the novel progresses, we come to understand the extent to which the good-hearted Lord Darlington was played by the Nazis as their most important British pawn pre-WWII.

Stevens comes to terms with this sad fact—that he served a duped Nazi-sympathizer—as much as he comes to terms with his long suppressed feelings for Miss Kenton. That is to say, barely at all. But enough for us to see the sadness within him. He is such a lonely man. At least he was a great butler. At least he has dignity. To question his years of service would be to question his very identity.

Reading the book I couldn’t help but picture Anthony Hopkins as Stevens. I assumed the movie captured Stevens’s subtlety of character, no matter how the story itself was altered. It’s the soul of the source material one wants to be loyal to. Getting hung up on creating an exact adaptation is pointless and detrimental. Movies function very differently than books.

But some adaptations make one wonder. If that isn’t part of your movie, one asks of the book’s very reason for being, why bother adapting it at all?

Which is perhaps a bit harsh when applied to The Remains of The Day. It is, after all, a much lauded movie. And watching it again, there’s much to appreciate. The final scene, one not in the book, is perhaps the movie’s most moving. A bird flies into a parlour. Stevens chases it, grabs it, and releases it out the window. He closes the window, locks it, and disappears inside Darlington Hall. Trapped. Forever.

Yet despite its strong performances, stately direction, and thoughtful compositions, the rest of the movie, aside from a handful of powerful scenes, didn’t do much for me. I was surprised at how much it deviated from what seemed to me the core of the novel: the character of Stevens.

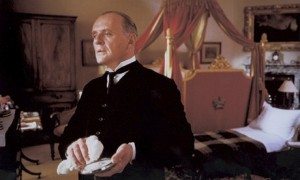

Anthony Hopkins is an incredible actor. His Stevens is a finely tuned creation. But he is surprisingly emotional. In his every interaction with Lord Darlington, Miss Kenton, and anyone else, his emotional turmoil boils beneath his not quite calm exterior. He is a picture of torment. Subdued, British torment, but obvious torment just the same. His trip to see Miss Kenton is about one thing only: romance. He knows it, wants it, openly talks of it to strangers, is hugely disappointed when it’s not to be.

What happened to the dignity of the butler? To being nothing but a butler when in the presence of others? The Stevens of the film is a man about to burst in every scene.

I know. It’s a movie. You have to communicate inner turmoil somehow. If Stevens showed nothing, we’d never understand his true self. And yet… So much of the book’s power comes from the fact that not even Stevens understands his true self, or indeed whether there’s a true self left to understand. The movie version tells us he knows exactly what’s going on, and is fighting tooth and nail against it. I wonder what the effect would have been if only in his private moments did we see the cracks in his façade.

Beyond that, the adaptation, written by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, suffers in the way almost every book-to-screen transformation does. The story feels attenuated, glossed over, presented quickly in order to squeeze in as many scenes as possible, without taking the time to dwell on the most significant ones.

The sequence during which Stevens’s father dies, in the midst of an important gathering, is the highlight of the book. It’s devastating. The movie version undercuts the intensity by allowing us to see the emotional turmoil bubbling up beneath Stevens’s not-so-very calm exterior. Again, I wonder if keeping that emotion tamped down until Stevens found himself alone wouldn’t have had a greater impact. In the book, Stevens relates the story of his father’s death during this momentous dinner as his proudest moment, the moment when he became a great butler.

His own father’s death! And he kept his emotions under wraps while performing at the height of his abilities. This is what he sees as dignity. There’s a sadness here of a depth rarely encountered.

Perhaps the scene most effectively conveyed in the movie is the one in which Miss Kenton (played by Emma Thompson), coming to Stevens in his private room, asks to see the book he’s reading. He backs away from her, holds the book to his chest. Is it shocking in some way? She comes still closer. Prises it from his fingers. But it’s only a melodrama, not shocking at all. This is, strangely, the most romantic moment they have together. It’s as powerful in the movie as in the book.

The end of the movie attempts to heighten Stevens’s emotional loss by making another change, a predictable one, but one that I think lessens the sadness. In the novel, after Stevens parts with Miss Kenton, he sits alone on a bench on a dock, watching the evening lights flicker to life, marveling at the people around him applauding. A stranger on the bench beside him says it’s because the evening is the best part of the day. One should enjoy the remains of the day, he adds. Is it too late for Stevens? He’s lost Miss Kenton. He lost her long ago. He devoted his life to a man whose foolishness aided Hitler. And now? Now he has nothing but a mostly empty mansion to return to, where he will spend the rest of his life. He thinks to himself he needs to practice his bantering. Americans like to banter. If that’s what his employer needs of him, it’s something he’ll have to work on.

In the movie, it’s hardly a surprise that it’s Miss Kenton he sits beside on the bench, and Miss Kenton who says that evening is the best part of the day. Not so lonely when your lost love is beside you.

I’ve no doubt I would’ve enjoyed the movie more had I not just read the book. Always thus. How many times must I learn this lesson to remember it? In this case, I did it for science. I did it for you! Don’t make my mistake. Pick one or the other, and stick to it.

One of my favorite movies, and one of my favorite books. I teach the novel, not the film, in my IB Language & Literature course.

I think you’re missing something. In the novel, Stevens is not able to hide his emotions in the course of carrying out his duties. While he does manage to serve drinks after learning his father has died, he is noticeably in tears. I think the film did a great job of showing his struggle to remain “fully clothed,” and that he was not always able to do so. Stevens did not always act the professional: his early interactions with Miss Kenton attest to that, in both the book and film. To remain fully clothed except when entirely alone was Stevens’ ideal, but we must judge how well he achieved it.

You’re right in that he didn’t always achieve his ideal. He recounts others asking him at times, “are you all right, Stevens?”, to show that they could see something going on within him that he wasn’t able to hide. I think I was just reacting to Hopkins’ portrayal overall, and it struck me as so different from the Stevens I’d just read narrating his story. Perhaps I am being a little unfair.

As for scenes being rushed, or having less impact, I suppose it’s the same thing. Having just been so affected reading the book, the same scenes in the movie didn’t hit with anything near the same power. Stevens and Miss Kenton watching his father out the window, retracing the steps from his fall, is such a central moment in the book, yet in the movie it didn’t seem especially moving.

But again, if one hadn’t just read the book, these issues would probably not be there.

Yeah, I think you might’ve just been too high off the book. That scene has always worked perfectly for me. The whole treatment of his father is handled extremely well, imo.

I do think the ending of the book is more powerful, but I’m not sure the book’s ending would have worked as well in the movie. There are some differences between the book and movie that slightly annoy me. While I don’t show the film to my students, I do recommend it to them–and warn them not to get it confused with the novel.

Oh, and I wouldn’t say the movie glosses over important scenes. I think it handles the weight of each scene extremely well. Though I confess, I haven’t watched it in some years.

Intelligent discussion, much appreciated. I will have to watch this film as I’ve never seen it.

So glad I found your post! I am having the opposite problem where I recently saw the movie and was excited to start the book. Except once I began, I instantly recognized the use of the delusional narrator, very much like Humbert Humbert in Lolita. I know you’re supposed to work through the lies and delusions to find the untold ‘truth,’ but I already know that he’s sadly mistaken about everything he values (having seen the movie) and now I just don’t feel like finishing the book. And I’m the type of person who usually finishes a book, especially a really great one like this one.

I thought Hopkins’ performance very well captured the character’s rigid adherence to misplaced values, and knowing that, I find it difficult to continue “listening to” (reading) Stevens’ voice rattle on and on about the ‘great butler’ and dignity.

Clearly, the book is brilliant and far superior to the movie, but because I watched the movie, my relationship to the narrator is tainted from the beginning. Instead of first finding him charming, perhaps eccentric, and giving him a chance and then realizing he’s pathetic and crazy would have been much more satisfying. I feel like my ‘journey’ with regard to experiencing this book has been ruined.

I think that with Lolita, even if you know the guy is a pedophile before opening the book, you still let Nabokov’s virtuosity with language toy with you. Here, it’s not happening. Stevens is crazy. That is all.

So I thought I would ask whether you think finishing the book would be worth it. Is there more to discover than the sad fact that this character has spent his entire life loyally serving a man who stupidly helped a hateful political group bent on exterminating an entire race of people, as well as intellectuals, artists and others?

Going in, I was hopeful that the book would explore how good people rigidly following convention and behaving the way they thought they were supposed to, ended up helping or working for the Nazis. That issue has been a preoccupation of many Germans in art, literature and film since WWII and I thought perhaps this book would explore that from a Japanese perspective. Except it doesnt quite work when the narrator is crazy, which is what I have to call Stevens going on and on for multiple pages about dignity and great butlers.

If I continue reading, will I find more than just pity and contempt for Stevens? I find myself repeatedly in disbelief at his utter lack of a clue!

Please excuse (delete) the comma between “to” and “ended” in 2nd to last paragraph. Sorry about that!

Given your take on the character, perhaps reading onwards is not called for. But I wonder if you’re being rather too harsh towards Stevens? Calling him crazy feels unnecessarily cruel. He devoted his life to serving others, and so forgot to learn how to take care of himself. This isn’t insanity. Or if it is, we’re certainly all of us insane.

I see the closing scene of the film differently to how you describe. It’s a beautiful scene, Stevens releasing the bird, and the camera flies upwards with it, soaring above the house and estate with the emotional closing soundtrack – I see this as him releasing Miss Kenton and his love for her, accepting that he should now finally let her go.

I guess the thought of him continuing to suffer his lost opportunity is just to much for me to contemplate!

This is such a lovely film, a real favourite.

I came looking for your opinion because i felt , upon just reading RoD, that some of the subtleties of the two characters were, in the film, almost right but not quite.

I thought the film was excellent and the actors more capable than any of expressing those nuances, but of course they are being directed for a visual medium. With a novel of we have no interference.

I say do look at both but recognise the difference.