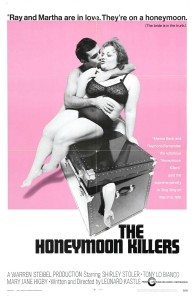

François Truffaut called The Honeymoon Killers (’69) his favorite American film, Antonioni loved it, and John Waters regularly lists it among his favorites. That’s an impressive group of fans for a low-budget, independent movie made almost entirely by cinema newcomers. The original director was Martin Scorsese, who’d at that point made one movie, but he spent so much time (and, consequently, money) shooting the first week that producer Warren Steibel fired him. Scorsese’s replacement lasted two weeks before being canned by Steibel and replaced, finally, with the film’s screenwriter, Leonard Kastle. It was Kastle’s first and last time directing a movie. He’d never written a movie before.

François Truffaut called The Honeymoon Killers (’69) his favorite American film, Antonioni loved it, and John Waters regularly lists it among his favorites. That’s an impressive group of fans for a low-budget, independent movie made almost entirely by cinema newcomers. The original director was Martin Scorsese, who’d at that point made one movie, but he spent so much time (and, consequently, money) shooting the first week that producer Warren Steibel fired him. Scorsese’s replacement lasted two weeks before being canned by Steibel and replaced, finally, with the film’s screenwriter, Leonard Kastle. It was Kastle’s first and last time directing a movie. He’d never written a movie before.

It’s based on the true story of the famed “lonely hearts killers,” a couple who from ’47 to ’49 answered personal ads from lonely ladies, met them, stole what they could, and occasionally killed them.

The movie is a completely unromantic portrait of the couple and their misdeeds, which low-budget unromanticism ends up being kind of wonderfully romantic. In a terrible serial killer kind of way.

I’d never seen it until last week (in a theater, on 35mm, hooray!), and it’s certainly no wonder why John Waters loves it. It plays like the movie that invented his mojo. As for Truffaut and Antonioni, they must have been taken by the realism. There’s nothing Hollywood about it. It stars Shirley Stoler as Martha Beck, who in the film as in real life is no waifish model, and as the suave Ray Fernandez, Tony Lo Bianco, who’d been in two prior movies and would show up a couple of years later in The French Connection. They both play terrible people, and they’re both totally committed.

It’s shot in black & white by a first time cinematographer who I swear has no idea what he’s doing. Heads float at the bottom of the screen, seemingly not attached to bodies. People lurk halfway in the frame. Close-ups are too close or not close enough. Strange pans drift here and there. And every now and then a peculiar choice—or accident—is perfect. The effect is weird and disorienting.

The entire movie is weird and disorienting. Coming from a newbie writer, the structure is completely out of whack. Which means you never know what’s coming next or when or why, even. You know it’s a movie about a murder spree, but where’s the spree? It never really arrives. Not that people aren’t murdered. They are. At weird times.

It’s a movie that takes forever to get where it’s going and ends well before you think it’s going to. It’s like it’s all beginning and ending without any middle.

The murders are as blunt as everything else. They’re ghastly. But the movie is odd enough and funny enough—not hilarious by any means, but just funny enough—that you’re not quite as appalled as you might be. And it really is strangely romantic. Martha is nothing but jealousy and rage, Ray is nothing but charm and guile, and what they see in each other remains a mystery, yet the result is a lovely, awful, doomed couple you can’t help but be fascinated by.

I liked it.

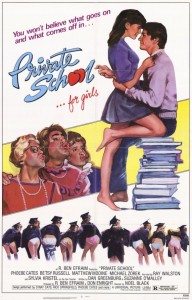

I can’t say the same for the next love story I watched (late the same night, on cable, I was awake, there was whiskey involved), a little film you may have forgotten called Private School, from the early days of the teen movie revolution, ’83, when teen movies were still R-rated. How had I missed this one at the time? I’m going to assume it was owing to its girl-centric nature. I can see myself scorning the VHS box at the video store. I mean look at that poster. Some kind of awful love story? No, when I was 12 I had a backlog of horror to catch up on, like Scanners and Basket Case.

I can’t say the same for the next love story I watched (late the same night, on cable, I was awake, there was whiskey involved), a little film you may have forgotten called Private School, from the early days of the teen movie revolution, ’83, when teen movies were still R-rated. How had I missed this one at the time? I’m going to assume it was owing to its girl-centric nature. I can see myself scorning the VHS box at the video store. I mean look at that poster. Some kind of awful love story? No, when I was 12 I had a backlog of horror to catch up on, like Scanners and Basket Case.

Speaking of that poster, all those ladies showing their asses? That’s literally the final freeze-frame shot of the movie. Which tells you almost all you need to know.

But only almost. The weird thing about Private School is that it’s two movies in one, either one of which could have been, well, maybe not “good,” but certainly better. One movie is a genuinely heartfelt love story, albeit one dripping in outrageous amounts of cheese, between dopey-in-love-nice-kids Jim and Christine, played with gee-whiz innocence by Matthew Modine and Phoebe Cates.

Jim and Christine decide early on to make like a couple of horny teenagers and have sex. But, you know, not cheap sex. Beautiful sex. In a hotel room. With candles.

Watching them mooning at one another at school sickens hot popular girl Jordan. Why should a stud like Jim be into a loser like Christine? She decides to steal him away.

Which sort of makes up the other half of Private School, the terribly unfunny soft-core teen titty movie half, in which various boys dress up as girls and sneak into locker rooms, and various people I can barely remember have sex here and there while chauffeur Ray Walston watches (was Ray itching for more high school flicks after Fast Times?). It is in every way awful. Aside, I guess, from the nudity. The women are definitely naked. My 12-year-old self might have given it a pass on that alone, had I bothered to watch it.

The dueling halves of Private School are never really brought together, and the worst of both worlds are achieved. Focus on the love story and maybe you get a Valley Girl. Focus on the trash and maybe you get a Joysticks or a Zapped!. But half-ass them both and you get Private School.

Eventually Jordon gets Jim in her room and propositions him, but being such a swell nice guy, he declines. Only who should see him leaving her room? Christine! On noes!

Wouldn’t you just know it, though, those two sweet kids make up and hit the hotel room. Only it’s not right. Jim’s not into doing it in such a “perfect” atmosphere. And then somehow they end up on a beach at sunrise and do it on the sand. Watching which all I could think was “Sand? You’re screwing in the sand, without so much as a towel? Ouch.”

And then its graduation, everyone’s happy, and the girls shows us their freeze-frame asses.

I did not like Private School. If I want to see adorable Phoebe Cates, I’ll stick to Gremlins.

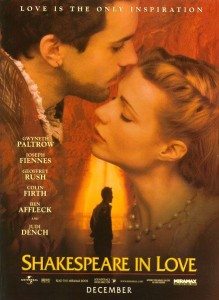

The next night I decided to upgrade budget and class to complete my love story trilogy, and went with perennial “I can’t believe it won Best Picture!” punching bag, Shakespeare In Love (’98).

Here’s the thing about Shakespeare In Love: It sets out to tell a comic/tragic love story in the style of a Shakespearean comedy, set in 1593, with Shakespeare as protagonist, using his own (fictional) doomed love affair with an unattainable daughter of a rich merchant to inspire his famous play, Romeo And Ethel, The Pirate’s Daughter, and pulls it off flawlessly.

Here’s the thing about Shakespeare In Love: It sets out to tell a comic/tragic love story in the style of a Shakespearean comedy, set in 1593, with Shakespeare as protagonist, using his own (fictional) doomed love affair with an unattainable daughter of a rich merchant to inspire his famous play, Romeo And Ethel, The Pirate’s Daughter, and pulls it off flawlessly.

Sure, it’s silly, it’s light, it lays on the weepy music awfully thick, and so on and so forth, but Shakespeare’s comedies were no different. In a word, Shakespeare In Love is deft. Originally written by Marc Norman, playwright Tom Stoppard, no stranger to screwing with Shakespeare, was brought on to rewrite it, and his way with words shows.

So why the disbelief at its winning the Best Picture Oscar? Because it beat out the favorite, Spielberg’s Important War Movie, Saving Private Ryan. World War II, Hanks, Spielberg, it seemed like a lock. Problem was that, aside from the truly stunning battle sequences, Saving Private Ryan is a fat, flopping turkey of a movie, so sappy and devoid of non-manipulated human emotion it drove famed novelist/screenwriter William Goldman to write this amazing review.

(The real best movies of 1998 are Rushmore, Babe: Pig In The City, and the other WWII flick, Malick’s The Thin Red Line, only the last of which was nominated for Best Picture. If anyone was snubbed that year, it was Malick. But that’s a discussion for another time.)

There’s something to be said for knowing what kind of movie you’re making, and making it well. Spielberg, as usual, wanted it all, and wound up flailing. Director John Madden knew exactly what he was making, and nailed it.

I don’t often go in for sappy romances, but when they’re this fun I do. They’re not often this fun. Stoppard packs it with references to Shakespeare’s plays. Dialogue, props, characters; everything seems to point to one play or another. The movie’s stuffed with anachronism jokes, too, which work in a way Mel Brooks could only dream of.

Even the performances are good. Not surprising among the surfeit of fine British actors on display, but for the we-need-to-cast-them-to-make-a-buck American actors, who would have thought Gwyneth Paltrow could be so winning? And Ben Affleck? His part is small, but he does a fine job with it. And I am not a fan of Ben Affleck.

The key to any love story is the chemistry between actors. If you don’t buy the lovers, your movie is doomed. Why else would something like The Honeymoon Killers work? You can’t make logical sense of why these two are together, but when you see them, you accept it. In Shakespeare In Love, Joseph Fiennes and Paltrow are mad for each other the second they meet. Their love animates every scene. And the only reason Private School contains anything at all worth praising is because Modine and Cates are on exactly the same page, performance-wise. They both nail dumb, innocent love.

Ah, yes. Dumb, innocent love. It’s the best kind. Who’d want knowing, wise love? Sounds terribly boring. Love ain’t about logic, it ain’t about experience, and it ain’t well and wisely decided upon. When it’s got you in its grip you’re just as likely to write a tragic play as murder strangers or, worst of all, have sex on the beach sans towel. This is what the movies have taught me this week. I hope it helps.

Yes. Shakespeare in Love. It just works. Plus Geoffrey Rush.

There are not enough good love stories. It’s hard to make love both believable and inspiring because it’s so durn squirrelly. And you can quote me on that.

“Help! Help! I gots squirrels in mah pants!” — The Evil Genius. (I think I got that right?)

Hey wait! I didn’t say I gots squirrels in my pants! Those are SECRET SQUIRRELS and now you’ve ruined the surprise.

I guess that’s love.