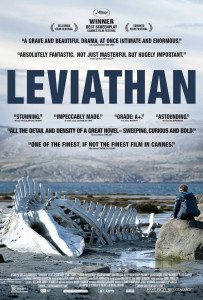

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s film Leviathan flings its impressive bulk against the seas, the stones, the sky. The world, however, doesn’t take much notice. For as big as this film is, the world is larger, and the seas, the stones, the sky do not care.

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s film Leviathan flings its impressive bulk against the seas, the stones, the sky. The world, however, doesn’t take much notice. For as big as this film is, the world is larger, and the seas, the stones, the sky do not care.

They will last and you will not. They are too big to fail. You might as well give up now.

Leviathan presents us with a Slavic variation of Job’s story, set on the northern coast of Russia. A hot-headed man is muscled off his property by the town’s boorish, intoxicated mayor — the scenario a version of eminent domain gone wrong. Our protagonist Kolya (Aleksey Serebryakov) rages against the corrupt political elements, enlisting his second wife (Lilya; Elena Lyadova), his teenaged son (Roman; Sergey Pokhodaev), and his old army buddy, now a savvy Moscovite attorney (Dmitry; Vladimir Vdovichenkov) as variously willing and reluctant support.

Alas, the mayor is the mayor. The state is the state. The world is the world. Who are you to challenge it? Have another drink, pal. Crack another bottle of vodka and forget it.

The film Leviathan tumbles in grays and whips in rainy, unwelcoming expanses. As such, it is quite beautiful, particularly as seen from a snug, velvet theater seat. Here, the fire-lit shell of an old church out-shines the faded icons that once graced its holy walls. Kolya’s modest home, built of weathered wood, gleams from the touches of uncountable fingertips — but can anything so fragile hold against the wrecking power of steel and time?

Not in Leviathan. The rolling waves, the bulldozer, and the great beasts carry unrelenting, pummeling power and before them we all shatter into dust.

Written by Zvyagintsev and Oleg Negin, Leviathan transmits substantial intellectual and emotional fodder. Its story of struggle meanders to include local law enforcement, infidelity, youthful revolt, and — with its fingers in everything — the church. Leviathan‘s characters remain ill-defined, but not in a way that telegraphs slack. They are rather too busy with themselves to bother explaining their motivations to interlopers like you.

It is, on the whole, a film I appreciated less than I might have. I gloried in some of the cinematography — the hulking skeleton of a whale contrasted with the rotting hulls of ships; the dawn that refuses to break; unending slabs of fish slopping down a conveyor belt — and I considered its themes and meaning for days, but listlessly. I did not come to care for Leviathan‘s characters or to commit to Kolya’s quest.

It felt a bit overfull with hopeless grandeur, but that’s appropriate once you sink your teeth into its opinions of organized religion. Leviathan has much to say about the church, the state, corruption, and the truth of god. I am unsure, however, how much I cared to listen.

And then there is an extra tragic turn towards the end that remains unexplained, except symbolically, perhaps, by a pig at a trough. Someone dies and we are left to wonder by whose hand? In Leviathan, are we done in by innocence or by corruption? Either explanation might be true.

Which is a neat trick, if you can pull it off as well as Andrey Zvyagintsev does.

Leviathan won Best Screenplay at last year’s Cannes film festival. It is Russia’s official selection for the 87th Academy Awards. It is not Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, but if you’re seeking penance, understanding, and acceptance you could do a lot worse than Leviathan.

Just bring along a couple bottles of vodka so you can keep up with Kolya. The film is 141-minutes long and you’ll have time to drink at least three.

I thought it was phenomenal. I think living in Poland, and with a Polish family, brings me closer to its import.

I can see how that would make a difference. Also; how not being exhausted from caring for a newborn, that too might make a difference.

Sounds intriguing, anyhow. I’ll check it out sooner or later.