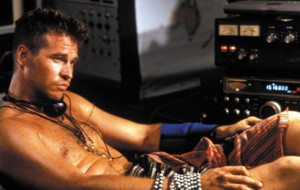

Few financially disasterous, creatively compromised clusterfucks are as entertaining as the 1996 (and third overall) version of The Island of Dr. Moreau. Watching it, there’s no doubt something went horribly, horribly wrong. What madman, you wonder immediately, cast Marlon Brando and Val Kilmer in the same movie? Brando was well known by that point as being beyond difficult and probably insane, and Kilmer, at the peak of his fame following Batman Forever and Heat, was renowned as a powermad egomaniac drunk on his own genius.

The first of half of Dr. Moreau is arguably a good movie. Or at least an incredibly entertaining bad one. The scene where the smallest man in the world (Dominican actor Nelson de la Rosa), dressed identically to Brando, plays a miniature piano on top of Brando’s grand piano is inarguably one of the greatest scenes in the history of cinema.

The second half of Dr. Moreau descends quickly into running, shooting, and blowing things up. What little attention is paid in the first half to the themes of man playing god and what it means to be human is jettisoned in favor of crazy beasts wreaking havoc. Which beasts, featuring make-up effects by essentially every artist working for Stan Winston Studios, look fantastic.

What happened? Where did this adaptation go wrong?

A new documentary from director David Gregory, Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau, endeavors to supply the answers.

Which in short may be summed up thus: Jungle madness.

Directors have a long history of losing their minds making movies in the jungle about men losing their minds in the jungle.

Directors have a long history of losing their minds making movies in the jungle about men losing their minds in the jungle.

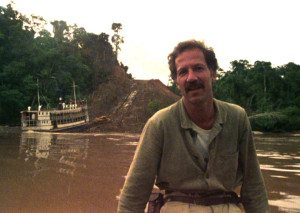

I recently rewatched two other paired jungle madness movies, Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (’82) and Les Blank’s contemporaneous making-of doc, Burden of Dreams. Fitzcarraldo tells the story of a man (played by the genuinely mad Klaus Kinski) who, during the Brazilian rubber boom of the early 1900s, is inspired to build an operahouse in the tiny village of Iquitos. To do so he needs money. Which he will earn through exploiting a field of untapped rubber trees. Untapped because the river leading there is impassible. Unless, he realizes with a burst of lunatic inspiration, he takes a neighboring river to a point one mile from the first, and, with the help of the natives who view him as their mythic white god, drags his boat over the mountain.

Burden of Dreams tells essentailly the same story, only it’s Herzog dragging the boat. Among other harships, self-imposed and otherwise, Herzog elected first to eschew models, and second to eschew an easy slope. He would drag a real boat up a 40% grade for one mile over a mountain. The engineer he hired, who designed the system of pulleys Herzog used, quit before they began, after estimating a 70% chance of failure, which failure would kill some 40 or 50 people, more or less. (His system was meant for nothing steeper than a 20% grade.) Herzog was willing to take the risk.

Unlike Herzog, who after years of setbacks and struggles finished his film to much acclaim and continued reverence, young Aussie director Richard Stanley failed to finish his dream project. Ever since he’d read H.G. Wells’s novel as a child, he’d wanted to make a movie of Dr. Moreau. After making two small films, the first an underground sci-fi hit (Hardware from ’90, derided by the mainstream as a Terminator rip-off, but loved by cult movie aficionados of the time), and the second, Dust Devil (’92), plagued by re-edits and distributor conflicts (but also gaining cult fame), Stanley convinced New Line to finance his utterly mad version of Dr. Moreau.

Four days into shooting, New Line fired him.

The final project, helmed by Hollywood vet John Frankenheimer (who gets a bad-movie lifetime pass for having made the ’60s masterpieces Seconds and The Manchurian Candidate), bears almost no resemblance (beyond monster design) to Stanley’s vision.

So devastating was the process that Stanley essentially disappeared from movie-making, and aside from work on some recent documentaries and short subjects, has never fully returned.

Before disappearing, wracked with grief at his movie being taken away from him, he hid out in the same jungly area of Cairns in northwest Australia where Frankenheimer was shooting, and eventually found his way back to the set, despite being contractually obliged to go nowhere near it. Since the camera crew had been fired along with Stanley, no one but the actors recognized him, and none of them minded his donning an extra’s dogman mask and appearing in his own movie.

That’s right. Richard Stanley is in The Island of Dr. Moreau as a background dogman.

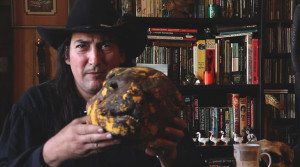

Stanley is a quite a character. He’s interviewed extensively for Lost Soul, and comes across as a somewhat wild-eyed, mystical shaman. He shows off artistic renderings of scenes as he envisioned them, the ones which convinced New Line to make the movie, and they are fucking wild. I can’t imagine any studio making anything like it, but oh man, if they had, we might be talking about Dr. Moreau in the same breath as Fitzcarraldo or even the most famous madman-in-the-jungle movie, Apocalypse Now.

Speaking of which, if you’ve ever wondered at he similarities between H.G. Wells’s Dr. Moreau novel and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, you aren’t alone. The, shall we say “borrowing,” ended the friendship between Wells and Conrad. Conrad claimed Wells’s book wasn’t an influence, but the similarities are legion.

Francis Ford Coppola is the other director who famously lost his mind making a movie about Marlon Brando playing god in the jungle, and Hearts of Darkness is another stunning documentary about an out of control jungle production. Coppola, like Herzog, finished his film and, like Herzog, paid a certain mental price for his efforts. Neither director ever mounted another movie as laboriously lunatic in scope.

All three films have another commonality: Each lost its leading man partway into production.

Coppola began filming Apocalypse with Harvey Keitel as Willard, but after a week or so of shooting, Coppola fired Keitel and hired Martin Sheen. Who would go on to have a heart-attack, yet still finish the film.

Herzog wasn’t so lucky. His leading man was Jason Robards, with Mick Jagger playing his simpleton sidekick. After finishing just under half of the film, Robards came down with some kind of jungle fever, flew back to the States, and was told by his doctor he could never return. Half a movie had to be scrapped. Death for most productions, but Herzog refused to give up. He hired Kinski to replace Robards. Jagger, who had a life in The Rolling Stones to return to, couldn’t commit to starting over. Herzog wanted no one else for the part, so he wrote it out of the script.

Stanley wasn’t supposed to be making a $35 million movie (double that, or more, in today’s money). Originally New Line approved an $8 million budget, but then Brando signed on, and then Kilmer, and suddenly it was a major motion picture. Immediately New Line booted Stanley in favor of Roman Polanski, but Stanley finagled a private meeting with Brando in which he so impressed the man that Brando refused to make the movie without Stanley directing.

Originally, James Woods was to play Moreau’s henchman, Montgomery, and Kilmer was to play the lead, Edward Douglas. For reasons unclear, Kilmer then demanded his shooting days be cut by forty percent. Without Kilmer’s fame, the movie was sunk, so Stanley fired Woods, gave Kilmer the smaller part of Montgomery, and hired Rob Morrow, then well-known for the TV show Northern Exposure, as his leading man.

When Stanley was fired, Morrow quit. Frankenheimer hired David Thewlis to replace him. Sad to say, Thewlis isn’t interviewed in Lost Soul. Not the biggest surprise, but what’s odd is that his name isn’t mentioned in the doc at all (for that matter, neither is Ron Perlman’s (Perlman plays the hyena-swine)). No one has a story about him? Thewlis, in later interviews, refers to Kilmer as a “nutjob,” and Frankenheimer as having “one of the ugliest souls.” Of his experiences making movies, Thewlis says, “Island of Dr. Moreau was the worst.”

The movie almost lost another star in Fairuza Balk, who when Stanley was fired fled 500 miles to Sydney to fly home. The production brought her back. She’d signed a contract. She could not escape.

At least Herzog and Coppola had their personal mad visions to compel them and their casts and crews. Few people aside from Herzog believed he’d ever haul his boat over the mountain. But he believed. And he did it. Coppola, of course, is Coppola. His brain melted by the heat of the Philippines sun or not, the man could sell ice cubes to Eskimos; not for five seconds did he stop selling his movie to those making it.

Frankenheimer, on the other hand, was loathed by everyone, and apparently loathed them back. Of Kilmer he said, “If I was making The Val Kilmer Story, I wouldn’t cast that prick!” Or so the story goes.

When Stanley was directing, and after Brando and Kilmer were hired, the studio brought on Michael Herr to rewrite the script. Herr, a novelist, didn’t work much for Hollywood. Most famously, he wrote the voice-over narration for Apocalypse Now (and co-wrote Full Metal Jacket). Stanley was thrilled to have him. The studio didn’t stop there. For the next rewrite they brought on Walon Green, famed for writing The Wild Bunch, and still Stanley was thrilled. You’d almost think the script was fantastic by then.

Frankenheimer hated it. He threw it out and brought on writer Ron Hutchinson, a scripter of TV movies. I’m going to go out on a limb and say the prior script, which I haven’t read, is better. It couldn’t possibly be worse.

Lost Soul isn’t even close to being as powerful a documentary as Burden of Dreams of Hearts of Darkness, but because of its subject matter it’s non-stop entertaining, filled with Aussie crew-members and actors describing the outrageous antics of stars and directors. Certainly it would have been magnificent to hear Val Kilmer talk about it, but he declined. Not terribly surprising. According to everyone interviewed, he was much despised, and appears to have been a large part of why Stanley was fired.

Kilmer seemed intent on fucking with the young director, telling him his scenes wouldn’t cut together, donning a random blue armband, refusing to speak lines as written or audibly or sanely, such that once the first dailes made it back to New Line, the company figured Stanley had completely lost control.

Even with Frankenheimer in charge, it was a mad production. Brando being Brando, he never showed up on time, never learned his lines, painted his face white, demanded to wear an ice bucket on his head for one scene, and befriended the smallest man in the world, insisting he be in every scene with him, dressed identically, thus screwing over actor Marco Hofschneider, whose character, M’Ling, the loyal dog, was Moreau’s sidekick in the script.

As far as New Line was concerned, there was no question of finishing the movie. Even if it bombed, they’d make out better than scrapping it. Would the whole thing have truly fallen apart had they kept Stanley on? Well, probably, yes. Stanley did not seem temperamentally prepared to handle a big-budget production that required he manage egos the size of Brando’s and Kilmer’s. He may well have been doomed the moment he set foot in the jungle.

Historically, jungles have long attracted the half-mad and megalomaniacal. It’s no surprise, then, that in modern times it’s film directors who’ve been seduced by their primordial charms. Lured by the idea of the jungle, by the idea of an outcast pursuing his dreams unsullied by the norms of modern society, they take on the persona of their subject, and maybe not by accident. They yearn to be consumed by the jungle, however much they fight against it. They yearn to go mad. In the context of these stories, madness is freedom.

I saw Lost Soul at the SF IndieFest. Richard Stanley spoke after the screening, rebutting some of the claims made about him in the film, and further explaining his ideas for what his movie could have been. He concluded by saying that, owing to Lost Soul, there was renewed interest in his original script for Dr. Moreau. One can only hope another production is mounted. With or without Stanley directing, it’s sure to drive someone out of their skull. Let’s hope a documentary crew is on hand to film it.

Sleep-deprived, I watched the first half-hour of The Saint with Val Kilmer; it is beyond words. His disguises are Dadaist masterpieces of insanity.