The Soviet Union was a strange place. Strange to anyone who didn’t live there, and, I’d have to expect, strange to those who did. Or maybe I’m projecting. To those who grew up in the system, it’s all they knew. Which sure, you can say that about anyone, anywhere, to some extent: you only know what you know. But for one thing, the Soviet Union existed pre-internet. Few windows onto the west were available. For another thing, few people were allowed to leave. When they did, either legally or illegally, they often would up like Robin Williams in Moscow On The Hudson—freaking out in grocery stores. How can there be so much coffee?!

The Soviet Union was a strange place. Strange to anyone who didn’t live there, and, I’d have to expect, strange to those who did. Or maybe I’m projecting. To those who grew up in the system, it’s all they knew. Which sure, you can say that about anyone, anywhere, to some extent: you only know what you know. But for one thing, the Soviet Union existed pre-internet. Few windows onto the west were available. For another thing, few people were allowed to leave. When they did, either legally or illegally, they often would up like Robin Williams in Moscow On The Hudson—freaking out in grocery stores. How can there be so much coffee?!

The rulers of the Soviet Union created an image for its citizens during the 20th century of a unique, modern country on its way up, a place in every way superior to the capitalistic west. They had work to do, yes, they hadn’t surpassed the west yet, but work was the very point: teamwork. A whole country working not for individual gain, but the betterment of all. Or so the propaganda went. Some citizens were notoriously more equal than others.

Here in the west, we knew they were evil. We knew communism was wrong. We knew our every-man-for-himself, get-rich-and-screw-the-little-guy capitalistic system was superior, both practically and morally. We knew we would win. And we did, eventually. The Soviet Union was dissolved in ’91. (And not a single problem with capitalism since. What luck!)

Here in the west, we knew they were evil. We knew communism was wrong. We knew our every-man-for-himself, get-rich-and-screw-the-little-guy capitalistic system was superior, both practically and morally. We knew we would win. And we did, eventually. The Soviet Union was dissolved in ’91. (And not a single problem with capitalism since. What luck!)

But for many years, sure as we were of our superiority, the Soviets were equally sure of theirs. They got their hands on the A-bomb. They beat us into space. And their hockey team was the best the world has ever known.

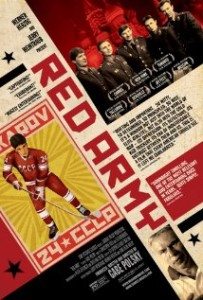

Red Army tells the story of the Soviet national hockey team, focusing on the ‘70s to the USSR’s dissolution, through the story of player and eventual team captain, Viacheslav Fetisov, one of the world’s greatest hockey badasses. Fetisov is interviewed extensively, and he’s quite a character. He’s very, in a word, Russian. Taciturn. Emotion boiling within, but not expressed verbally. So too the other players interviewed, who suffered and succeeded with him.

Suffered because we’re talking about the Soviets. Selection for potential spots on the national team began with kids under 10. Once on the team, players were taken to a training camp where they lived, apart from their families/wives/kids/etc., for eleven months of the year. Successful, in part, for the same reason. They lived and breathed hockey. It was their world, and their world contained little else.

For the Soviet leaders, hockey, and other sports, were seen as an extention of both war and politics. To win sporting events was to show the superiority of the communist system. Which is to say, they took it seriously. Very seriously. Say the wrong thing and find yourself carving ice sculptures in Siberia for the rest of your life seriously. When the team loses to a ragtag bunch of American nobodies in the 1980 Winter Olympics, you fear for their lives.

But (spoiler) they are not killed or shipped to Siberia. Or are they? Most of the veterans—players and staff—are cut from the team. No word on what became of them. Makes one wonder.

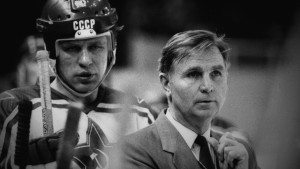

The Soviet hockey team was led for years by “the father of Russian hockey,” Anatoli Tarasov, for whom hockey was an art form. He wanted his team to move like ballet dancers, whom he studied, whose moves he taught to his players. His training methods were unique. He stressed creativity above all else. To Tarasov, the game was essentially a patriotic endeavor, stressing teamwork and comradeship.

Watching the Soviet team play, their differences from the rest of the hockey world become instantly clear. The players swirl around one another as in a dance, smooth and flowing, defenders scoring goals, forwards looping backwards, everyone passing constantly. Americans and Canadians had never seen anything like it. They had no idea how to defend against it.

In the two years leading up to the 1984 Olympics the Soviet team was unbeated. Two straight years. They won gold in ’84 and again in ’88.

Then came Gorbachev and the end of the Soviet Union. The remainder of the film chronicles the efforts of Russian players to leave the country and play for the NHL, an effort led by Fetisov, who for years was kept in-country by his politicians and his scheming coach (a man nobody on the team ever liked, who declined to be interviewed for the movie).

Under Soviet rule, defection was an act of political defiance, and worse, an example to the world of dissatisfaction with the communist system. Even after the collapse of the regime, the government was loathe to allow someone as famous as Fetisov to leave. They feared he’d never come back. But as a sign of their goodwill, they offered to let him go, so long as he sent 90% of his salary back to mother Russia.

Eventually Fetisov makes it to America, only to find new challenges in the NHL. Nobody plays like the Russians. Nobody understands what he’s trying to do on the ice. Mostly they just get in fights. Not quite the elegant game the Russians were used to.

Red Army is written and directed by Gabe Polsky. He previously made a small movie I missed, The Motel Life, and has worked as a producer for Werner Herzog (on The Bad Lieutenant), who returned the favor by co-producing Red Army. Polsky skillfully builds his story. It begins with a kind of jokey interview scene with Fetisov, goes into the history of hockey, and then, without being overbearing in the least, becomes political, and eventually something even more.

I found myself entranced with Fetisov’s journey. The way he ages. His allegiance to Russia waning and waxing. Without ever stating outright what it’s up to, the movie moves beyond sports and politics to something purely human, to the experience of growing up, growing old, of how we face the past, or fail to face it.

It’s fascinating to see where Fetisov ends up. And why. And how Russia’s history brought him there. I liked how little Red Army states outright. Instead it suggests. I found my mind branching off in many directions by the film’s end. Why did the Soviet national hockey team succeed the way it did? Cruel treatment of players? A brutal practice regime? In part, sad to say, yes. Yet something else is going on here too. The spirit of teamwork. Of achieving a collective goal. For a team sport, isn’t this the ideal? What do we lose if we focus only on personal success?

This sounds like it would make a good double-bill with Whiplash.