The catch with adapting books for film is that the only way to make your adaptation truly engaging for those who know the book is by deviating significantly from the source text. But there’s a catch to the catch. If you deviate from the source text — like say Blade Runner did — then it’s not going to satisfy those people who want to see a faithful adaptation of the book. So you have to be unflaggingly true to your source material, unless no one really knows the source material, in which case there’s a catch…

There’s only ever one catch, see, and that’s Catch-22.

There’s only ever one catch, see, and that’s Catch-22.

What Catch-22 means is you can’t win. The game is rigged from the ground up. The rules, which you can’t read, forbid you from winning.

Unsurprisingly, the catch with Catch-22 — the Mike Nichols adaptation of Joseph Heller’s novel — is one even a film about the catch itself cannot successfully navigate. This is because it is nearly impossible to navigate a Catch-22 successfully. It is as difficult as rowing a one-man inflatable raft from the Mediterranean Sea to Sweden.

Even so, the film Catch-22 is a marvelous experience, if you’ve read the book. It is not transcendent, like Blade Runner or The Shining, but for a film that hews closely to a sprawling, unfilmable novel there is much satisfaction to be found within its frames.

I first read Catch-22 in high school. Since then, I’ve read it numerous times and for a long while referred to it as my favorite book. I was one of those irritating kids who carried around a self-annotated copy so I could sit in public spaces and look bright. Except there was a catch: anyone who tries to look bright in such a pathetic way is clearly not too bright.

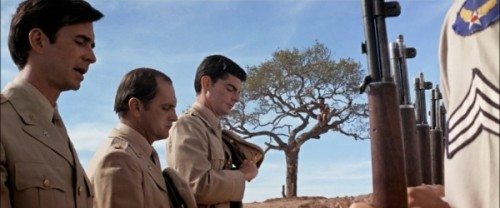

The novel spins a web around a squadron of airmen on the (fictional) Italian island of Pianosa during World War II. Primarily following the character of Yossarian, Heller weaves an expanding tale of institutionalized insanity. Or, explained succinctly: war.

Yossarian’s group commander keeps raising the numbers of missions the men must fly. Yossarain doesn’t want to fly any more missions because doing so puts his life at risk. He tries to get out of flying missions by saying he’s crazy (or by being crazy) but there’s a catch; only a sane man would try to get out of flying life-threatening missions, so if he tries to get out of flying them, he’s demonstrably not crazy. If he flies them, then he can be crazy but as soon as he asks to get out of flying them; he’s not crazy.

Or, as Heller writes:

There was only one catch and that was Catch-22, which specified that a concern for one’s safety in the face of dangers that were real and immediate was the process of a rational mind. Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he were sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle.

It is a wry, dark, funny satirical novel that picks apart the constructs of society (specifically militarized society) until everything comes pouring out of you like the intestines of a perforated radio gunner. Catch-22 is one of the modern world’s great novels, keeping company with Infinite Jest and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It did not result in, however, one of the modern world’s great films.

Catch-22 is only a fascinating film, made with deep affection. It’s filled with screwy bit performances presented by a sprawling, confusing cast that keeps you off-kilter. The script marvelously assails the insanity that stokes the core of the novel, but there’s a catch. In succeeding at skewering the insanity, it fails to find time for the suffering that makes that insanity matter. There are impressionistic sequences — some lifted right from the novel — that show us true pain, but only from a remove.

We understand why Yossarian wants out, but we don’t share his dread. It does not overtake us.

If you’ve read Catch-22, then, in the film, you might keep pace with whom Orr is (Bob Balaban) and why his maddening stove tinkering matters; or why Aarfy Aardvark (Charles Grodin) behaves so poshly and what that behavior satirizes; or even why Bob Newhart‘s Captain Major has no choice but to be promoted to Major Major and remember, from the book, that he’s actually Major Major Major Major.

You will know the chummy evil of Milo Minderbinder’s syndicate (Jon Voigt plays Milo) and, deep in your gut, taste the foulness of his chocolate-covered cotton. If you haven’t read the book, shame on you. Also, good luck getting beyond the frenetic wrongness that lacquers the topmost layers of the film of Catch-22. It is this wrongness that is the point of the film (and the novel) but wrongness demands its sacrifice of human lives to gain conquering strength.

In the film, those human lives are lost but the men and women remain sketchy — such as that of Hungry Joe, or half of him at least. When sacrifices get fed into the maw of war, it’s hard to miss them as anything but symbolic signposts.

So Catch-22 is a fascinating but flawed adaptation of Catch-22 if you’ve read Catch-22, but if you haven’t read Catch-22, than Catch-22 is an ambitious but largely impenetrable film exploring a book you haven’t read. Catch-22, I guess.

Perhaps, also, this catch partly explains why I’d resisted watching the film until now. I feared I could not win, because winning is against the rules.

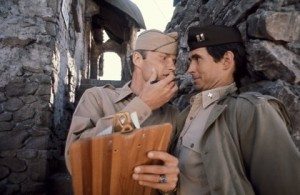

But a lack of hope is not a lack of ambition, albeit insane ambition. Mike Nichols, best known for The Graduate, does a beautiful job here creating and stoking the sane frenzy that drives Yossarian (Alan Arkin). The temporal fluidity of the novel gets reduced in Buck Henry’s script (Henry also plays Lt. Colonel Korn), but survives recognizably. David Watkin’s cinematography is in turns lovely and macabre. The performances, which also include roles by Martin Sheen, Art Garfunkel, Martin Balsam, Anthony Perkins, and Orson Wells, build into a Scylla of terrible power but limited range.

I’ve read the book and, so, I greatly enjoyed being somewhat disappointed by the film, which made me want to read the book again, and even to re-watch the film (with commentary by Mike Nichols and Steven Soderbergh) which was only disappointing in a satisfying way. I’m guessing that if you haven’t read the book, you’d probably be confused, or bored, or — like much of American in 1970, when it was released — disinterested and unimpressed. Audiences and critics at the time compared Catch-22 unfavorably to M*A*S*H, another anti-war film that applied black humor to expose the insanity of military action. That film, one of my all time favorites, goes deeper, reaches farther, and feels more insane for the sickness corrupting its soul.

Turns out that Catch-22 came out a day late, and a dollar short, and no one much wanted to watch another assault against our aggressive natures. It’s too bad, I think, but I am unsure.

I might be crazy, but I really enjoyed Catch-22 despite its shortcomings. I suppose you’d have to be crazy to like it, but then if you’re crazy, who cares what you think?

I guess that’s the catch.

Well. I am intrigued. Maybe I’ll give it another shot. I tried watching it once, at least twenty years ago, and found it so unfunny and awful I turned it off after about 45 minutes. So who knows? Maybe I was crazy then. Or maybe I was not crazy then, but am now. I mean certainly I’m crazy now. So I’d probably better watch it.

I encourage you to do so. It’s a very handsomely mounted production with a lot of heart, just sort of… too much on its plate. The book has too many characters that all need to be known and loved and understood — there’s no way to do that without conglomerating them (awful idea), trimming them (vastly problematic) or doing what nichols/henry did: just throwing them all out there with excellent (and recognizable) actors and hoping people kept up.

I had to stop it and start it a billion times because: baby. But really wanted to rewatch it immediately after. Some great sequences and more insane than funny.

Oh how fun! That makes already two stir crazy people in this room, for I too love the book and felt sort of positively befuddled by the film. I guess in times of so much easy digestible book and film fare, our mind invariably hungers and lusts for more complicated, intriguing, mind-bogging or plain crazy matters. This might be the one endearing quality about humans, who knows?! I might try to get my hands on a copy once more and re-watch the film to see if I was crazy by then and am plain sane now :O

Yes Trinity. You need to watch it again 55 times, but then I’ll raise the number of times to 65. Then 75. Be careful, though, those bastards are trying to kill you.

… only if they can CATCH me!

Also my favorite book. Definitely a flawed movie, but beautifully cast, at least. The scene with Orson Welles is worth the price of admission. And there is no one but Alan Arkin to ever play Yossarian. No one.

Indeed. It’s stunt casting that hits almost every mark. Charles Grodin is sublime as Aarfy. Newhart kills as Major Major. Jon Voigt though… meh. He’s too naturally slimy. They should have got Robert Redford and played it straight. Made it so much harder to hate Milo Minderbinder, the all-American asshole.

I never read the book. I love the movie. So sue me.

Huh. Go figure. You’ll hear from my lawyer.