Yann Demange’s freshman feature ’71 seems straight-forward, but that’s a sly deceit. The picture isn’t simple by any means. It’s actually as complex as any desperate scramble for survival must be — and frequently as heart-stopping.

Yann Demange’s freshman feature ’71 seems straight-forward, but that’s a sly deceit. The picture isn’t simple by any means. It’s actually as complex as any desperate scramble for survival must be — and frequently as heart-stopping.

Like a hunted individual, ’71 remains, of necessity, ignorant of everything beyond its immediate requirements for life. The periphery here doesn’t cease to exist, only our momentary consideration of it. In the film ’71, as in reality, the intricacies of politics, the recognition of our neighbors’ equality in fear and fury — things such as these play soft second fiddle to keeping the blood flowing to our brains. The complexities of life get pushed aside. They remain a luxury that those who feel safe can find time to assess.

If you’re lucky, come morning light, that might be you. Or the complexities might kill you first. Either way, you will not feel safe when watching ’71.

In marshy greens and French Connection gritty greys, this film opens upon a young British soldier, Private Gary Hook (Jack O’Connell*), training for his unit’s deployment to Germany. We see his competence, but little more. We watch him visit his young son in a government home, a place with which it is intimated he is more familiar than most. And there you have it: the entirety of Private Hook in ’71. Simple. Stripped down. He is a man like any of us. There is no origin story. You don’t need one to want to live until morning.

In marshy greens and French Connection gritty greys, this film opens upon a young British soldier, Private Gary Hook (Jack O’Connell*), training for his unit’s deployment to Germany. We see his competence, but little more. We watch him visit his young son in a government home, a place with which it is intimated he is more familiar than most. And there you have it: the entirety of Private Hook in ’71. Simple. Stripped down. He is a man like any of us. There is no origin story. You don’t need one to want to live until morning.

Hook’s unit doesn’t go to Germany. They get sent to North Ireland at the height of the Troubles instead. A scant briefing conveys half a minute’s worth of establishing information to the untested soldiers and to us: the Protestant Loyalists live in these blocks; the Catholic Nationalists live over here; the Nationalists are split between the IRA and the Provisional IRA. Watch out. It isn’t safe. Here’s your gun. Go forth.

That’s slim data with which to navigate 1971 Belfast’s animosities and alliances, and that’s the point: to this day, no one with an unlimited amount of time or access could accurately explain that chaos. Complexity requires room to breathe, and that was in short supply then, and also here in this film.

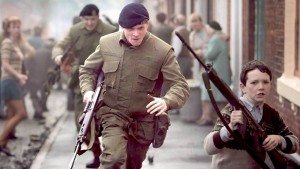

Hook’s unit backs up the local police during a neighborhood weapons search. Their novice left-tenant sends them in under-equipped. Very quickly, in a sequence of shocking, overwhelming anger, they are over-run. Hook gets separated, beaten, and barely escapes alone into the morass of a Belfast night, 1971.

Hook’s unit backs up the local police during a neighborhood weapons search. Their novice left-tenant sends them in under-equipped. Very quickly, in a sequence of shocking, overwhelming anger, they are over-run. Hook gets separated, beaten, and barely escapes alone into the morass of a Belfast night, 1971.

Like the Indonesian film The Raid, this set-up serves as enough to open the curtains on a non-stop thundering through one seriously fierce night. Unlike The Raid, ’71 abandons both genre conventions and dramatic subterfuge in favor of startling simplicity. Simplicity based in reality, not martial arts expedience or Hollywood tropes. One man tries to live through the night. That’s the whole story told in ’71. The rest — the complexity — that’s for you to collect and assemble and puzzle over from your safe theater seat, if you get through the night with Gary Hook. It is left peripheral not because it is unimportant, but — conversely — because we are too often unable to consider the details and choices that have put our lives in danger in the first place.

We do not truly get to know anyone during the course of the film, including Private Hook, but this is far from a flaw in the script. We understand less of Northern Irish politics, the aims of the players, or the daily sacrifices of the besieged civilians. ’71 lives and breathes basic survival. That is all it has time for, which is just so. What we see hidden around the edges, however; this content travels farther than what we’re told — a brave thing for a screenwriter to trust to put into practice.

We do not truly get to know anyone during the course of the film, including Private Hook, but this is far from a flaw in the script. We understand less of Northern Irish politics, the aims of the players, or the daily sacrifices of the besieged civilians. ’71 lives and breathes basic survival. That is all it has time for, which is just so. What we see hidden around the edges, however; this content travels farther than what we’re told — a brave thing for a screenwriter to trust to put into practice.

Demange uses Gregory Burke’s sparse, excellent script to tell you as little as possible and to explain almost nothing at all. If this world is complicated, what of it? All you need to do is live though this block or this moment. All anyone needs to do is survive. Ignore the complications and get by, or — once your life falls back into your hands, if it ever does — try to consider further. Ask yourself what is important.

O’Connell’s Gary Hook says little to stay alive, but the performance bleeds life. He does what he must, and that’s never what John McClane or Snake Plissken might. He is not trying to save the hostages, or negotiate a fragile peace between factions. There is no mano-a-mano final confrontation because life contains few heroes and no villains. All Hook wants is to get home. The fact that this simple request is near impossible to grant, that’s the misfortune of life in Belfast, both for our protagonist and those he encounters.

And notice what happens to most of them.

Damange does a clever job of wielding a quick camera and applying confrontational sound and score to keep tensions high without sacrificing authenticity. This is how handheld cinematography is supposed to feel, and when it’s supposed to feel it. You will not be requested to suspend your disbelief by ’71. You will, in fact, only notice how often other films have tricked you into doing so in comparison.

Damange does a clever job of wielding a quick camera and applying confrontational sound and score to keep tensions high without sacrificing authenticity. This is how handheld cinematography is supposed to feel, and when it’s supposed to feel it. You will not be requested to suspend your disbelief by ’71. You will, in fact, only notice how often other films have tricked you into doing so in comparison.

This is an action film that makes you wish there was less action. A film that makes you loathe the thought of sequels; let it be done, this madness. Let these children — so many children, so old so fast — grow at least as wizened as young Private Hook.

In response to the army’s arrival, Demange gives us grandmothers slamming rubbish bin lids against the pavement, over and over like wind-up monkeys. We get boys bullying their way through lines of men, so they can threaten and kill. We receive smoke and ruin and blood and — over it all like a sheet of black ice — confusion, suffering, pain.

How can we live like this? How can we survive? How did we do so then and how do we do so now? What is it there, on the periphery, we cannot get the space to see?

’71 looks and sounds just right. It is not the story of a hero’s victory or a villain’s defeat. It is a story about the stunning strain of survival. That is more than enough.

* O’Connell is making a big name for himself lately with a starring role in this film, Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken (which I haven’t seen) and the British prison film Starred Up, which is brutal and good. If you haven’t noticed him yet as an actor, you will soon. He’s like Sam Worthington but with the opposite amount of talent.