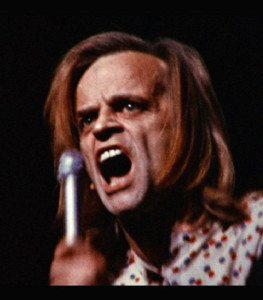

In the mind of German actor Klaus Kinski, the world has ever conspired against Klaus Kinski, full as it is with people so wretched, insipid and awful, it’s a wonder he, Klaus Kinski, has found the will to live for as long as he has. Or so one surmises reading what must be the most incredible autobiography ever written, in English translation titled Kinski Uncut.

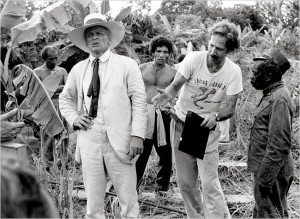

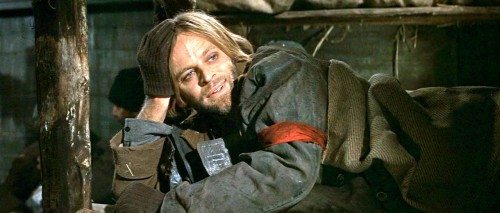

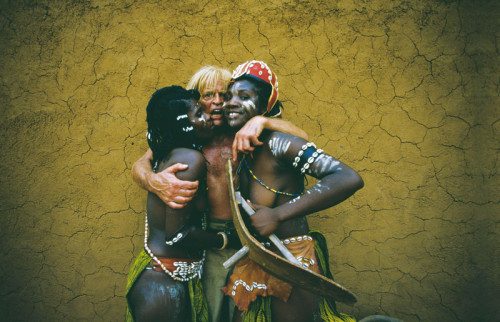

Kinski’s book is the ranting tirade of a megalomaniacal madman. It is obscene. It is pornographic. Half of it is surely lies, and just as surely the other half is pure bullshit. That he could maintain this histrionic vitriol/impassioned emotional outburst for over 300 pages is astounding only if you’ve never seen him interviewed or caught between takes of his movies, such as in Werner Herzog’s documentary My Best Fiend (’99), which documents Herzog’s working relationship with Kinski. They made five films together between ’72 and ‘87, probably the five Kinski is best remembered for: Aguirre: The Wrath of God, Nosferatu, Woyzeck, Fitzcarraldo, and Cobra Verde.

According to IMDB, Kinski acted in 136 films. According to Kinski, he acted in over 300 (and turned down over 1000). According to Herzog, the number is impossible to know, so many films did Kinski act in, in so many countries. Kinski chose roles based primarily on what they paid. Where they were to be shot and when they were to be shot also figured in to his calculations. But mostly it was about the money. Which he earned in massive amounts and spent with utter abandon. He turned down parts offered by Fellini, Pasolini, Arthur Penn, Ken Russell, and Spielberg (for a role in Raiders of The Lost Ark. Kinski writes, “But as much as I’d like to do a movie with Spielberg, the script is as moronically shitty as so many other flicks of this ilk.”).

In his book, Kinski has nothing but violent hatred and disgust for every single director he ever worked for, almost none of whom are named, aside from Herzog. He spends almost no time discussing his work in any of the hundreds of productions he was a part of. Movie-acting, as far as he was concerned, was a means to an end: money. Otherwise acting did nothing for him but suck dry his emotional well and drive him mad with rage.

Herzog, the one director Kinski spends time discussing, is not spared his loathing. A few sample passages of his thoughts on Herzog when first working for him on Aguirre:

While it’s quite obvious that I’ve never in my life met anybody so dull, humorless, uptight, inhibited, mindless, depressing, boring, and swaggering, he blithely basks in the glory of the most pointless and most uninteresting punch lines of his braggadocio. Eventually he kneels before himself like a worshipper in front of his idol, and he remains in that position until somebody bends down and raises him from his humble self-worship…

Herzog is a miserable, hateful, malevolent, avaracious, money-hungry, nasty, sadistic, treacherous, cowardly creep. His so-called “talent” consists of nothing but tormenting helpless creatures and, if necessary, torturing them to death or simply murdering them. He doesn’t care about anything except his wretched career as a so-called filmmaker. Driven by a pathological addiction to sensationalism, he creates the most senseless difficulties and dangers, risking other people’s safety and even their lives—just so he can eventually say that he, Herzog, has beaten seemingly unbeateable odds…He hasn’t the foggiest inkling of how to make movies.

According to Herzog in My Best Fiend, he and Kinski collaborated on the insults in Kinski’s book in an effort to increase sales. Well. Easy for him to claim with Kinski being dead (he died in ’91). Who’s to say that Herzog isn’t just as mad as Kinski?

Of filming Fitzcarraldo, Kinski writes:

Over and over again I refuse to stick to Herzog’s hair-raisingly crappy script or take his amateurish “direction.” I have to force him to accept every camera angle I want. I have to show that dimwit of a cameraman where the camera belongs, and I have to get the lens and the distance. I never “rehearse” a single scene. I say “Roll ‘em,” and I shoot only once.

Of working on Buddy Buddy, an ’81 Billy Wilder movie starring Jack Lemon and Walter Matthau, Kinski writes:

That piece of Hollywood shit with Billy Wilder is over, thank God. No outsider can imagine the stupidity, blustering, hysteria, authoritarianism, and paralyzing boredom of shooting a flick for Billy Wilder. The so-called “actors” are simply trained poodles who sit up on their hind legs and jump through hoops. I thought the insanity would never stop. But I got a shitload of money.

Why did Kinski act, then? It’s hard to say. I think because his emotional extremes wouldn’t have been tolerated in any other profession. And they were only tolerated in the world of cinema because Kinski was an amazing actor. I don’t know if Kinski was a “great” actor. I do know that he’s riveting to watch. He holds nothing back. He gives himself completely. And his giving both allowed him to live and slowly destroyed him, or so one must surmise reading his book. He felt no glamour about movies. Mostly he thought they were garbage.

At one point the German government informed Kinski that they were bestowing upon him the supreme distinction for an actor, The Gold Film Ribbon. Writes Kinski:

What gall! Who gave those shitheads the right to award me anything? Did it never occur to them that there might be somebody who doesn’t want their shit? What filthy arrogance to award me—me, of all people!—a prize! What does this prize mean, anyway? Is it a reward? For what? For my pains, sufferings, despair, tears? A prize for every hell, every dying, every resurrection? Prizes for life and death? Prizes for passion, for hate and love? And how did you shitheads intend to hand me the prize? As a gift? As a favor, like those tasteless hosts that the pope distributes like fast food? I’ll kick you! Or do I come submissive, whimpering? I’ll kick you again! And there’s not even a check. It’s outrageous!

Yet little of Kinski Uncut is about movies. Mostly it’s about the women Kinski screws. When I say this book is pornographic, I mean that about as literally as possible. It feels like he’s relating a new conquest on every page. To his credit, despite the ubiquity of his sexual exploits, no two descriptions are alike. He is prone to writing such sentences as, “Her little pussy is firm and almost round, like a field mouse.” As least when he’s being poetic. More often he writes things like this:

I’m starved for pussy, so like a satyr I drag any cunt to bed with me and fuck and fuck and fuck. Salesgirls. Waitresses. Chambermaids. Married women. Mothers. Black women from Haiti, Mozambique, Jamaica. Frenchwomen. American tourists. Students from Russia, China, Japan, Sweden, Chile, India, Cuba. A Bedouin. Schoolgirls from Africa. The naked black women from the Paradis Latin. The sweet asses from the Crazy Horse. The seven black models from Yves Saint-Laurent, all seven of whom devour me with the fleshy sponges of their wet, heavy lips.

It goes on. And on. If one is to believe him, he slept with every single woman ever to cross his path. It’s all a bit much in book form. Page after page after page it goes.

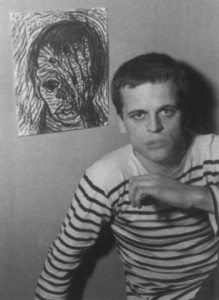

How did Kinski become Kinski? He was born pre-WWII, desperately poor. His younger years sound about as rough as can be. He was drafted into the army at the age of 16 as the war raged, and fought for maybe a week before being taken prisoner by the British. His parents died during the war. After it ended, he took up with theatrical types, and a career was born.

He would eventually tour the world in a one-man show in which he delivered, in costume, in character, famous soliloquies from Shakespeare and other writers. These shows were wildly popular. He writes:

My debut runs for six hours. The tumult of the jubilant and shrieking audience rages for over an hour, and after the performance they keep begging for encores and absolutely refuse to go home. This tour is the hardest I’ve ever done, but it’s also my greatest triumph.

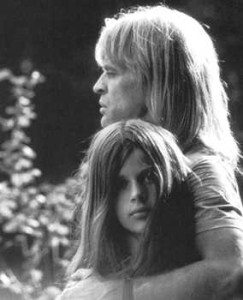

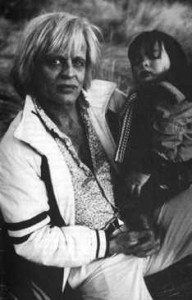

Kinski married early in life, a union from which his daughter Nastassja Kinski was born. He didn’t have much to do with Nastassja’s childhood. He left her mother and only saw them occassionally. Later on he met a Vietnamese woman, Minhoï, over whom he obsessed wildly for the rest of his life. Theirs was a tumultuous relationship, to say the least. They had a son, Ninhoï, who becomes the focus of the last part of the book.

Kinski simply can’t express the love he feels for his son enough. Again, page after page until it’s too much. Apparently his daughters were less inspiring, earning scant mention.

The thing about this book, though, is that it’s suprisingly well written for an insane actor. Not only that, but fighting through the pornographic sexism, the angry rants, and the spew of extreme emotional madness, one finally comes at the end to feel a kind of understanding and sorrow for the man. What demons must have possessed him! He never sounds happy. Never sounds satisfied. His was a life spent raging and fighting and fucking and never finding peace.

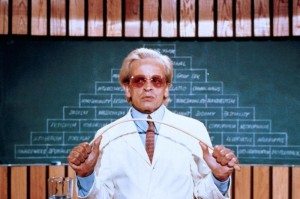

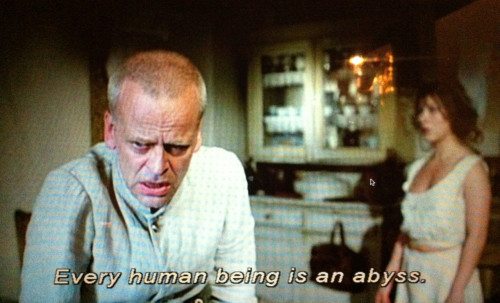

Referring to Woyzeck, one of the movies he made with Herzog, he writes about what acting does to him:

I find the totality of the metamorphosis most terrifying when I’m Woyzeck. Woyzeck, who murders his wife, the person he loves most in the world, and who then goes insane and drowns himself, orphaning their little boy. Suffering through that had as devastating an impact on me as if I hadn’t only always suffered as Woyzeck but continue to do so over and over. Malaria of the soul, recurring again and again. My total being is one large breeding ground for the shocks of the world past, present, and future. All living and dying, all vibrations pass through me. The entire universe pours into me, rages in me, rampages through me and over me. Annihilates me…I’m torn apart by the most conflicting feelings, the most conflicting thoughts—often at the same time, with no concern as to whether I can endure it…I don’t know how this will end…Now, today, I’d rather be poor, but without the nightmares and without the torture…I don’t want to be an actor! I wish I’d never been an actor! I wish I’d never had success! I’d rather have been a streetwalker, selling my body, than selling my tears and my laughter, my grief and my joy.

In My Best Fiend, his Woyzeck co-star Eva Mattes is interviewed by Herzog. She remembers Kinski fondly as a kind man, and, as an actor, always prepared and professional. Kinski must have had his good side. He was beyond magnetic, at any rate. Reading his autobiography, you’re not going to like him. But you will get a look into the mind of a man uniquely deranged.

I have watched many of Kinski’s films, at least all he did with Herzog plus some others. I also had the chance to watch some of his TV appearances in Germany, where the setup reminded me of “sensationalist” exhibitions of Victorian explorers, where wild animals were presented to a public which entertained the delusional notion of being educated and open-minded, when all they did was torturing the creatures and basking in their own superiority or normality. Such TV shows or debates would all end up infallibly with Kinski being enraged by moronic questions from the public and the moderators deepening his grieve by parading his temper and pulling at the right strings to provoke total outrage and display a rampaging Kinski on stage. I always wondered who was more insane and I realised it WAS Kinski by allowing them to do this over and over again, when his intelligence should have told him clearly what they were after.

I am still uncertain whether Kinski’s outbursts on whatever stage or medium were the result of his uncontrollable urge to vent disillusion and fury that seemed to burn in his inner furnace, or whether he was an endlessly narcissist person needing to build up myths about himself to satisfy his needs to be in the limelight.

Most of the time I am inclined to believe that there was some kind of genial, creative madness within him, which made him play his roles like nobody else would have done. Other times I believe to glimpse an incredibly intelligent pretender who is giving the world what they want to see while laughing himself silly inside, until he finally succumbed to his own myth with played madness becoming indistinguishable from involuntary one. Who knows?! Fact seems that whatever it was that drove him, it pushed him to leave some completely memorable acting heritage, with or without madness. If I need to endure such behavior to get glimpses of acting like his, hell I take it all the way. He was insufferable as a private person it would appear, but I do not care, for I only want to see the Kinski who acted like no “normal” person could have done. What he did or claimed in his private life … it does not effect his work in my eyes.

I believe that Herzog had a similar approach and endured Kinski with the clear vision that he needed to suffer the one Kinski in order to tickle the screen Kinski out of him. Sometimes that endurance was tested to the very limit and Herzog admittedly wanted to shoot Kinski at one point. (And who would blame him?!). But next day he knew that he would play with that fire again and again to obtain the performances he wanted from him. This is some sort of madness at Herzog’s end, I agree, but one that was calculated as a professional gamble and risk as I believe.

“I am still uncertain whether Kinski’s outbursts on whatever stage or medium were the result of his uncontrollable urge to vent disillusion and fury that seemed to burn in his inner furnace, or whether he was an endlessly narcissist person needing to build up myths about himself to satisfy his needs to be in the limelight.”

Both, I would say. Almost certainly. I think without question he was a terribly, horribly tormented man, who raged at everyone and everything around him. In the book, he clearly recognizes that he can’t control himself, but still–he can’t control himself.

I think you are right on this. And probably one urge fueled the other and viceversa.

How can you say he couldn’t express his love for his son? Nicolai was very precious to him. Have you not read his letter to him at the end of his book? You certainly didn’t mention it. I slogged through the whole sordid thing but that letter at the end showed Kinski to be a whole other person inside of that raging exterior.

Here’s the thing about reading: it is, as they say, fundamental. “Kinski simply can’t express the love he feels for his son enough.” What this sentence means is that he expresses his love overly. As in, a lot. It’s a figure of speech.

Didn’t Herzog plan to firebomb him? Only Kinski’s vigilant dog kept that from happening.