In the world of lost pieces of great movies, the two I most lament are the stop-motion spider sequence from King Kong, and the ending of Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons. Of the final scene, Welles says it was why he made the movie. And almost no one ever saw it. Why didn’t even one forward-looking individual have the common decency to save the negative of what Welles shot? Why not Robert Wise, who made the changes at the studio’s insistence? He couldn’t at least have saved the real ending while making the bastardized one? It’s maddening, I tell you, maddening!

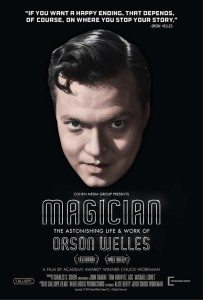

But I’ve already digressed. The new documentary by Chuck Workman on the life and films of Orson Welles, Magician, doesn’t go into the details on such matters. The film is an overview of everything Welles did in the arts; it never goes deep into any one film or play. As for his “astonishing” life, it shies away from his personal life and sticks to matters artistic.

Workman has done a nice job curating interviews, most old, some new, of Welles and the many people who knew and worked with him (well, there aren’t any new interviews with Welles. Too bad. That would have been something). Alongside copious film clips, the interviews narrate the story of the one-time boy-wonder who became, ever so briefly, a shining Hollywood star, before the town permanently turned its back on him.

Workman has done a nice job curating interviews, most old, some new, of Welles and the many people who knew and worked with him (well, there aren’t any new interviews with Welles. Too bad. That would have been something). Alongside copious film clips, the interviews narrate the story of the one-time boy-wonder who became, ever so briefly, a shining Hollywood star, before the town permanently turned its back on him.

Welles had a knack for pissing off the money-men. Magician makes the argument that Welles was the first and greatest indie filmmaker. The various directors interviewed certainly think so, from Spielberg to Scorsese to Linklater to Lucas to, of course, Bogdanovich.

For the most part, Magician is simply a love-letter to Welles, and in that it works just fine. It’s in no way a critical look at his work, never plunging deep into the reasons for his failures and myriad never-completed projects. It suffices to say that Welles went his own way, and his own way resulted in many a dead end.

Considering how beloved his work is now, it’s a shame so few of his films are available in anything close to watchable shape. Maybe if you’ve got a working VCR you can dig up an old copy of Chimes At Midnight. (Aha! A little research suggests a blu-ray restoration is coming soon. About time.) Otherwise one must be satisfied with the big ones. Which are indeed satisfying. Citizen Kane ain’t half bad, or so it has been said. And I’ll never get bored of Touch of Evil. Although there’s another case where a restoration was required. Universal screwed with the initial release after firing Welles, and it wasn’t until years after Welles’s death that Walter Murch, using Welles’s famed 58 page memo, restored Touch of Evil to what Welles wanted. Murch talks briefly about the restoration in Magician.

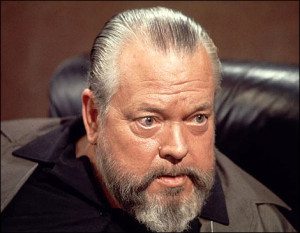

The first half of Magician is certainly more compelling than the back half. Orson’s brilliant youth as a theater impressario and master of the radio program and on through his best movies is a fun trip, but once into his later years as a lover of food and maker of partial films never completed, Magician becomes as diffuse and unfocused as its subject. Which sure, maybe that’s the point.

Welles’s companion from ’66 onwards, Oja Kodar, relates how once, toward the end of his life, she saw Welles watching The Magnificent Ambersons on TV. He was crying.

It’s hard to imagine how painful it must have been for Welles to have had so much of his work taken away from him and destroyed. He had so much to offer. For the last decade of his life he was lauded and loved, given awards and retrospectives, etc. But one must suppose there was something less than satisfying about being respected then, when he was long past producing the kind of focused work he was able to conjure up as if by magic when young.

It’s not many artists who, truly, were ahead of their time. Orson Welles was one.

I can’t believe you got through writing that without one “a workman-like job” joke.

I had to leave something for you.