Sometimes you just want to tie a rope around your neck, lean into the taut, blood-strangling tension, and — risking your own demise — seek sexual gratification. Or, at least, that’s what one might assume if they watched David Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars and Sion Sono’s Why Don’t You Play in Hell? back to back, just as we’re about to do in this month’s Mind-Control Double Feature.

Sometimes you just want to tie a rope around your neck, lean into the taut, blood-strangling tension, and — risking your own demise — seek sexual gratification. Or, at least, that’s what one might assume if they watched David Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars and Sion Sono’s Why Don’t You Play in Hell? back to back, just as we’re about to do in this month’s Mind-Control Double Feature.

In these two films, in very different ways, cinema leans itself over the edge of extinction just so it might get off on how devastatingly attractive the movies are.

Maps to the Stars

In theaters and available through various streaming services this very instant, David Cronenberg’s latest, Maps to the Stars, is an ouroborous of Hollywood self-cannibalism, essential incest, and generational decay. It is also, unfortunately, not quite as shocking as that sounds — but don’t despair.

In theaters and available through various streaming services this very instant, David Cronenberg’s latest, Maps to the Stars, is an ouroborous of Hollywood self-cannibalism, essential incest, and generational decay. It is also, unfortunately, not quite as shocking as that sounds — but don’t despair.

Or, rather, do despair; because the best we can hope for is the lusty pleasure of our own self-inflicted end.

The film locks modern-day Hollywood into a cramped cage and — gravage-style — force feeds it chunks of itself until it is both delicious and unfit for human consumption. Hooray for Hollywood! As the movie’s title suggests, this picture presents a road map to fame, celestial permanence, and all that such pursuits entail. Being a David Cronenberg film (from a Bruce Wagner script), it’s no spoiler to say that the picture’s harsh assessment of the Hollywood dream leans into the horrific.

Essentially Maps to the Stars contains three stories that are all the same (read: a stab at mythic). This is because there is nothing original in Hollywood, including the innermost matryoshka doll of this script, which a la the film of Catch-22, falls into the chasm it takes pains to warn us away from.

No matter, falling is half the fun.

As in Zeroville or The Player (which is far superior), Cronenberg’s latest weaves actual celebrities into the realm of fiction. Here, unstable Agatha (Mia Wasikowska) arrives in Hollywood on a bus from far-off nowhere. She immediately makes pilgrimage via hired limo (the driver, Robert Pattinson) to the long-ago incinerated home of child star Benjie Weiss (Evan Bird). Benjie, meanwhile, is busy making Lindsay Lohan look stable and sensible, as he, at 13, attempts to convince the producers of the ‘Bad Babysitter’ film franchise that his recovery from drugs is authentic and he can continue to star in the series.

In this commercial charade, Benjie gets assisted by his mother, Cristina (Olivia Williams), a character communicated as the polar opposite of William’s Rushmore role of Rosemary Cross. Benjie’s dad, the TV psychologist Dr. Stafford Weiss (John Cusack), meanwhile treats actress Havana Segrand (Julianne Moore) for her past trauma of childhood physical and sexual abuse at the hands of her mother, screen legend Clarice Taggart (Sarah Gadon) — whose seminal film Stolen Waters is about to be remade. Havana desperately wants to play the part her despicable mother made famous.

Hollywood, you see, eats itself.

Agatha is introduced to Havana by her Twitter friend, Carrie Fisher (as herself), so she can get set up as Havana’s ‘chore whore.’ This fandango accomplished, we have our trio of leads — Agatha:Benjie:Havana — each with their entourage of ghosts and ghouls, real and imagined.

It is a complicated morass of crazy, but hey: that’s Hollywood.

In Maps to the Stars’ first act, one doesn’t so much fall down a rabbit hole as come to fear one may have been, unwittingly, a rabbit for a disturbingly long time. And a rabbit in a big pot of rabbit stew, at that.

Evan Bird’s Benjie is as foul as last year’s oysters, evincing the sort of sadism that you normally only see kids his age apply to those picked last for gym. Mia Wasikowska’s Agatha conceals her burn scars under long gloves and stockings, but her emotional damage is undisguisable. Of the three, however, it is Julianne Moore’s Havana who takes the bitter cake. Her perfectly realized fading actress rings uncomfortably true, complete with a self-immolating absorption — another topic which comes back around.

Havana is so phony, so diseased, so deep into digesting her own rear end that death and life cease to contain meaning. You know the type.

I’d get into what happens in acts two and three, but to do so, even in small stitches, would be to unpick this somewhat raggedy sweater. Suffice it to say that Hollywood here symbolizes a reach for the stars, but one that falls shorter and shorter during each iteration. The magic of movies is a lie and each attempt to rebuild the lie only reveals how fluid our filmic foundations are.

Communicating this corruption via film may be ironic. The medium being the message.

In this infinite loop is where Cronenberg finds his meal. His is a film about how films are diseased genetic code. If there is incest here, it’s because without it there would be no life-giving at all. If there is destruction, it’s because each generation must clear the way for the worse to come.

As a film, Maps to the Stars proves its point by failing to be Sunset Boulevard. The ideas it invokes swirl, but don’t coalesce. It’s elements remain — in concert — atonal.

So why watch it?

Because promise unfulfilled inspires you to imagine ‘what if?’ Because this mutated dream is our decrepit inheritance.*

Cronenberg and Wagner see something authentic in their industry and world. They may present these images to us more as poetry than as treatise, but there is truth to be had. Moore is disturbingly exceptional as Havana. Bird’s characterization of Benjie is as frightening as anything Cronenberg has revealed about our insides since The Fly. While the ghosts and ghouls and incest and pseudo-mythical mumbo-jumbo may not mean much, or make much sense here: that’s where the map to the stars leads.

Cronenberg and Wagner see something authentic in their industry and world. They may present these images to us more as poetry than as treatise, but there is truth to be had. Moore is disturbingly exceptional as Havana. Bird’s characterization of Benjie is as frightening as anything Cronenberg has revealed about our insides since The Fly. While the ghosts and ghouls and incest and pseudo-mythical mumbo-jumbo may not mean much, or make much sense here: that’s where the map to the stars leads.

Maps to the Stars is what it exposes, an empty pursuit we cannot help but commit to. It is film, and film is what inspires us, what drives us, and what we’d be happy to die for.

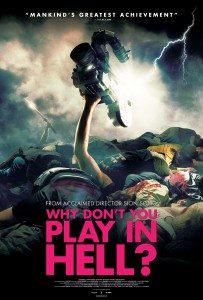

Why Don’t You Play in Hell?

If you saw Japanese director Sion Sono’s four-hour upskirt-photographer-ninja religious romance, Love Exposure, you might have some idea of what you’re in for with his latest: Why Don’t You Play in Hell?

If you saw Japanese director Sion Sono’s four-hour upskirt-photographer-ninja religious romance, Love Exposure, you might have some idea of what you’re in for with his latest: Why Don’t You Play in Hell?

Something batshit crazy, that is.

Sion Sono makes films that aren’t filled with subtext; rather they’re gelatinous pylons for an immense supertext billboard. His characters, his scenarios, his conclusions are just pawns in a grand game. You could try to make sense of each element on a logical, tangible level but that’s a waste of time.

Instead, just watch the cute little girl sing her toothpaste commercial jingle about gnashing your teeth unto agony and understand that — somehow, improbably — this film will end up being about making a great movie even if, or especially if, it kills you.

So Why Don’t You Play in Hell? is a question for you. Why don’t you play in the hell that is cinema? Just because it will inevitably end in a bloodbath of epic proportions?* Do not make me laugh. That is precisely what you are hoping for. Like Hirata (Hiroki Hasegawa) the aspiring film director who leads cinema production club, the Fuck Bombers, you understand that being part of a great film is more important than even your life.

So Why Don’t You Play in Hell? is a question for you. Why don’t you play in the hell that is cinema? Just because it will inevitably end in a bloodbath of epic proportions?* Do not make me laugh. That is precisely what you are hoping for. Like Hirata (Hiroki Hasegawa) the aspiring film director who leads cinema production club, the Fuck Bombers, you understand that being part of a great film is more important than even your life.

Thusly, Hirata leads his gang in pursuit of the ministrations of the God of Film (his words, not mine), attempting to make just one, measly great movie. Around them, two yakuza clans battle over who cares what: Territory? Honor? Foreign distribution rights?

You’ve got Muto’s clan (Jun Kunimura) — and it was Muto’s now adult daughter who captured our hearts with her toothpaste jingle — versus Ikegami’s clan (Shin’ichi Tsutsumi). Muto’s long-suffering wife will be released from prison soon and she expects to see Mitsuko starring in her first film. This poses a problem for Muto because Mitsuko is an uncontrollable dervish who has run off and been replaced in the lead role she was supposed to debut in.

Someone has to make a great movie. Someone has to make it to appease god, to satisfy family obligation, to ease the longing in their souls. Making this movie must take priority. It also must take place during gang warfare, using katanas if you please, for cinematic effect.

Scenes leap around Why Don’t You Play in Hell? like frisky lambs with mental deficiencies. Performances start cranked to 11 and ascend from there, with particular props to Shin’ichi Tsutsumi and his elastic faceparts. Children slide about in fields of blood, kisses are exchanged and delayed and spiced with broken glass, and everyone does his or her best to die spectacularly, on camera on camera.

It is a movie about our destructive addiction to cinema. It celebrates annihilating compulsion. It is a film that chokes itself to an inch of its life so that it might explode in joy at finding that a sliver of life remains. If you doubt me, simply consider the final scene of Why Don’t You Play in Hell?

One man runs through the streets, screaming. His insanity is his victory, just as it is Sion Sono’s.

Perhaps it could be yours as well? Consider that question, as you watch this month’s Mind Control Double Feature.

* There is no appropriate place in this piece to mention it, but the digital effects used towards the end of Maps to the Stars are laughably bad — so bad, from a director known for his ability to make the tangible revolting, that I wonder if they’re bad on purpose, as an alienation device? Also really bad: the digital blood effects used at the end of Why Don’t You Play in Hell?, but that’s entirely different. There they are bad because it does not matter: you will commit to cinema regardless of its resemblance to reality. Or in pursuit of exactly that kind of disconnect.