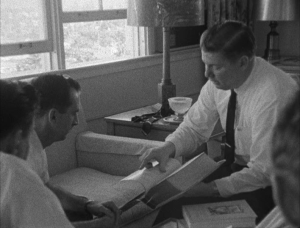

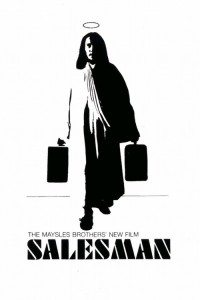

Salesman is one bleak documentary. Shot in ’68 by the Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin, it was intended to be the first “nonfiction feature film.” I can’t say exactly what they thought that meant, but surely it had something very much to do with telling a narrative using the tools of documentary filmmaking. “Direct cinema,” this sort of thing was called, or the more well-known term, cinema vérité. In Salesman, a number of Bible salesman are followed as they coldcall houses, attend sales meetings at headquarters, and hang around in motel rooms.

Salesman is one bleak documentary. Shot in ’68 by the Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin, it was intended to be the first “nonfiction feature film.” I can’t say exactly what they thought that meant, but surely it had something very much to do with telling a narrative using the tools of documentary filmmaking. “Direct cinema,” this sort of thing was called, or the more well-known term, cinema vérité. In Salesman, a number of Bible salesman are followed as they coldcall houses, attend sales meetings at headquarters, and hang around in motel rooms.

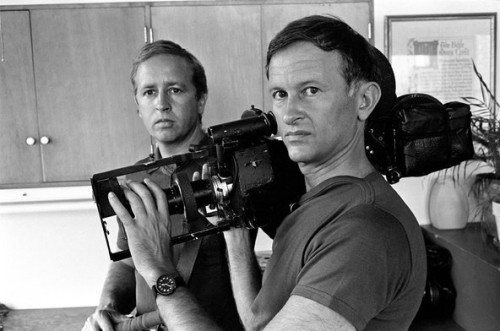

Of the two brothers, Albert Maysles was the cinematographer. “Was,” because he died last week, having outlived his younger brother, David, by almost thirty years. They’re best known for Grey Gardens and Gimme Shelter, their movie following a Rolling Stones tour that culminated with the murder at Altamont. Albert had a way with the camera. He knew how to stay out his subjects’ way while capturing their essence.

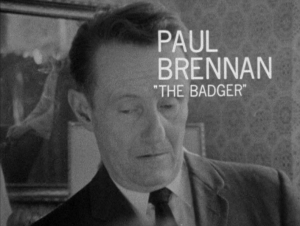

Though Salesman begins with a number of Bible salesmen as its subjects, one of them, Paul “The Badger” Brennan, becomes the focus. Paul’s lost his mojo. He can’t seem to make sales. We watch him try and fail over the course of the movie. What starts as frustrating becomes heartbreaking by the end. Not movie-style, emotional heartbreak; there are no tears. It’s heartbreak of a cold and bleak variety. The final salescall we see him on, accompanied by one of the other salesmen, is to see a man fold up and collapse in on himself. He attempts to sell his fancy, expensive Bible not to the typical family struggling with money, but to a well-off couple, and his frustration at not being able to convince even them, people with money, to buy what they admit is a beautiful Bible, is too much. He comes so close to yelling at them I’d almost say he yelled at them. The worst way possible for a salesman to break character.

Though Salesman begins with a number of Bible salesmen as its subjects, one of them, Paul “The Badger” Brennan, becomes the focus. Paul’s lost his mojo. He can’t seem to make sales. We watch him try and fail over the course of the movie. What starts as frustrating becomes heartbreaking by the end. Not movie-style, emotional heartbreak; there are no tears. It’s heartbreak of a cold and bleak variety. The final salescall we see him on, accompanied by one of the other salesmen, is to see a man fold up and collapse in on himself. He attempts to sell his fancy, expensive Bible not to the typical family struggling with money, but to a well-off couple, and his frustration at not being able to convince even them, people with money, to buy what they admit is a beautiful Bible, is too much. He comes so close to yelling at them I’d almost say he yelled at them. The worst way possible for a salesman to break character.

He stands, then. Hangs his head. Doesn’t move at all while his partner explains that he, Paul, has been having a hard time of it. And Paul remains motionless. Finally he looks up, smiles, thanks the couple, shakes their hands, leaves.

Earlier salescalls are no less enervating. One woman seems completely torn up inside considering her options. She doesn’t have the money, or at any rate says she doesn’t. Not even one dollar a week for this beautiful, full-color, $50 Bible? Not even one dollar a week. But she takes an agonizingly long time to make her decision final. Paul tries every argument he knows. Maybe it’s her husband’s birthday coming up? Nope. Nothing he says sways her. Nothing to do but pack up and leave.

The other salesmen have more luck. We see them make what seem like easy, friendly sales. All of them are perfect salesmen stereotypes. Which makes me wonder, how many fiction films about salesmen (Glengarry Glen Ross and Tin Men come immediately to mind) were influenced by Salesman? Maybe I’m giving it too much credit. The American salesman is a storied character. Maybe the most American of them all. Maybe the saddest, too. Poor, poor Willy Loman.

Everything these Bible salesmen do is tinged with sadness and fakery. Their patter with potential customers sounds exactly like patter, and I’m left wondering in every case whether or not the people being sold to recognize it as patter, and if they do, do they care? Do they like being sold to? I suppose they do, to some degree. It’s a relationship voluntarily entered into. Yes, come into my house and attempt to sell me what you’re selling. Do those who can’t buy let the salesmen in out of friendliness? So as not to feel rude turning them away without even hearing their pitch? Would the people who eventually buy have bought no matter the skill of the salesman? Do they just want to chat with someone? Are they lonely?

I also wondered what potential buyers were told about Albert and David Maysles. No one ever addresses the camera of the men behind it. So I had to read up on the movie afterwards. Turns out the Maysles were in a sense a part of the pitch. They told people they’d be part of a “human interest story” if they allowed themselves to be filmed while talking to the salesmen. This must have appealed to some. One can see how it may have helped sales. On the other hand, maybe people were content being of human interest, and not so interested in a new Bible.

The sales conferences are sad, too. As the salesmen pitch to their customers, their supervisors pitch to them. They’re pitched on the viability of their product, the usefulness of it, the goodness of it. These men aren’t selling junk, they’re selling something important. As the founder of their Bible company tells them, they’re doing God’s work.

Are the salesmen buying this line? They listen, impassive. And discuss it not at all later.

In one meeting, they have to suffer men among them standing up and announcing how very much money they expect to make in the coming year. Salesmen. They’re always selling. If not to a mark, they’re busy selling to themselves.

They all seem to drive big, American convertibles. A large part of the movie features them in Opa-Locka, Florida. Sunny and beautiful and poor and hopeless. They drive past streets named Ali Baba, Sharazad, Harem, Sultan.

Salesman works subtley. It’s not long, but it’s slow. Nothing exciting happens. It builds its story piece by heartbreaking piece until, in some cold little way, it empties you out and leaves you pining for an American dream long ago lost.