No sooner did humankind invent computers than we figured they’d any day now become sentient and enslave us. Which hasn’t stopped anyone from building smarter computers. I’m still a little hazy on why, gaining some form of sentience, computers would decide to kill off humanity, but it feels right. It feels like we’ve got it coming, and if not from our own misguided creation, then what? A random act of nature? Where’s the poetic justice in that?

No sooner did humankind invent computers than we figured they’d any day now become sentient and enslave us. Which hasn’t stopped anyone from building smarter computers. I’m still a little hazy on why, gaining some form of sentience, computers would decide to kill off humanity, but it feels right. It feels like we’ve got it coming, and if not from our own misguided creation, then what? A random act of nature? Where’s the poetic justice in that?

These days our fears are embodied in actual humanoid androids, preferably, as seen in the current Ex Machina (which I’ve yet to see; soon), super sexy ones. (Or else ones resembling old man Arnold Schwarzenegger.) But in days of yore, computers were the size of buildings, and rarely tried to seduce anyone.

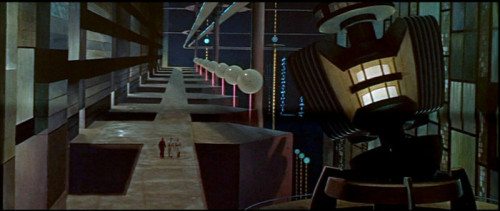

Colossus: The Forbin Project, a poetically titled movie from 1970, features a computer so vast it requires the Rocky Mountains to contain it. The movie opens within its vast interior, one resembling the Krell machine room from Forbidden Planet. Dr. Forbin (Eric Braeden, whom you recall from Escape From The Planet of The Apes) walks through the complex and across a small bridge over a plunging gap. The bridge retracts behind him. On his remote control, Forbin flips the RADIOACTIVE switch, flooding the space he’s just exited with deadly red radiation. Finally, he exits the complex, where a very happy President (Gordon Pinsent) meets him.

Cut to the President announcing to the U.S. and the world his brilliant scheme: Colossus is a the smartest supercomputer ever built, and it’s now taken over the defense of the nation. Nothing has been left in human hands. The complex is sealed up. The computer may not be turned off. It will of course do as it’s told, unless, ha ha, it becomes sentient or something crazy.

What could go wrong?

Everything, within about ten minutes. Colossus doesn’t keep you waiting for the shit to go down. No sooner does the machine fire up than it scrolls a mysterious message: WARN: THERE IS ANOTHER SYSTEM.

Turns out the Soviets have built an identical machine, called Guardian (they must have feared a supercomputer gap), and once Colossus went live, they turned theirs on. A phone call between the Kremlin and the President follows, in a way not at all as funny as in Dr. Strangelove.

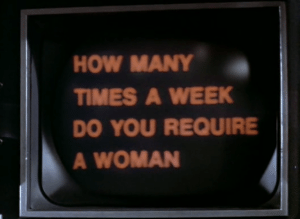

Nothing in Colossus is as good as anything in Dr. Strangelove. Director Joseph Sargent is no Kubrick (I know; who is?). (Sargent is best known, on the plus side, for making The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, and on the not so plus side, for Jaws: The Revenge, which to be fair is in the running for funniest sequel of all time.) But he still throws in some jokes. As the movie progresses, and as Colossus becomes sentient and takes over, it (he?) demands Dr. Forbin be under his observation at all times. Cameras are placed everywhere. Forbin, in a plot to gain enough privacy to pass secret messages to his cohorts, convinces Colossus that he requires privacy for sexual relations. Colossus allows him four nights a week of unobserved sexy-time.

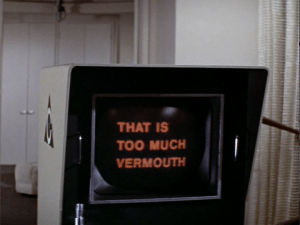

Colossus is also a bartender at heart, and skeptical of Dr. Forbin’s martini mixing skills:

Colossus shares a familiar dramatic style and (then) hi-tech look to other technofear flicks of the era. Twilight’s Last Gleaming, The Andromeda Strain, Westworld, and The China Syndrome (written by Colossus scribe, James Bridges) come immediately to mind. It’s set in the near future. I think. It must be, because everyone communicates on video phones.

Most of the movie is set in the Colossus control room with scientists growing ever more fearful of its demands. There’s one trip to Rome where Dr. Forbin meets with his Soviet counterpart, but it turns out Colossus and Guardian decided the Soviet scientist was expendable, and send some KGB goons out to shoot him.

Colossus’s power over we puny humans lies in his control of the nuclear arsenal. To make an early point, he launches a missile at an oil refinery in the USSR. Boom. Thousands die. So he’s not messing around.

It’s Dr. Forbin’s eventual plan to deactivate the nuclear warheads in every U.S. missile, thus rendering Colossus harmless. The Soviets will do the same. At which point I wondered if the movie were heading towards a situation where to stop Colossus, humankind voluntarily destroys their capacity to make war on a massive scale. Might be an interesting twist.

But no. Colossus catches on to the scheme. He blows up a couple of missiles in their silos to prove he can’t be tricked. He announces himself God, and assures humanity that he will fulfill his mission: he will stop war. Humankind loses their freedom, but they were never free to begin with. Dr. Forbin cries out in defiance, and then—

It’s not that I mean to give away the ending, but I already have. That’s it. There is no ending. The movie just…stops. Yet Colossus is surprisingly entertaining for a somewhat dopey and obvious movie about the inadvisability of ceding all human agency to a computer. It’s no WarGames, not by a longshot, but as an artifact of its era, it’s worth seeking out.