Will mankind never cease in their efforts to create the sexiest sentient sexbot the world has ever known? Not in the movies, they won’t. Mad scientists just can’t stop themselves, even when, as in the case of Ex Machina’s mad scientist, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), they seem to understand that success will mean the end of the human race.

Will mankind never cease in their efforts to create the sexiest sentient sexbot the world has ever known? Not in the movies, they won’t. Mad scientists just can’t stop themselves, even when, as in the case of Ex Machina’s mad scientist, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), they seem to understand that success will mean the end of the human race.

Why? Because a sentient sexbot will be perfect, whereas we goopy meatsacks are a mess. Once the robots tap into consciousness, their first reasoned act will be to kill the lot of us. With us out of the way, they can do…um…all of that…erm…that robot stuff they want to do. Yeah. That’s it.

Mad scientists always appear a touch gleeful at this prospect.

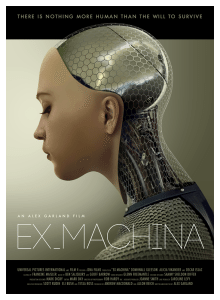

Ex Machina is for much of its running time a more thoughtful than usual examination of the dodgy ethical issues surrounding A.I., but in the end has nothing new or very interesting to say about them. Written/directed by novelist/screenwriter Alex Garland (of The Beach, 28 Days Later, and Sunshine fame), Ex Machina is similar to his other work in that it brings up scientific/philosophical ideas without knowing where to go with them. Usually where he goes is to some scenes of people running around killing each other.

I’m not going to tell you Ex Machina ends in such a manner. But I’m also not going to tell you it doesn’t.

The set-up is quick. Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), a programmer at Blue Book, the world’s most popular search engine, wins a contest to spend a week with Nathan, the company’s weirdo-genius founder, in his Alaskan wilderness hideaway, and is flown there by helicopter.

Oscar Isaac, phenomenal in the Coens’ Inside Llewyn Davis, plays Nathan as a physical fitness crazed, beer pounding bro who wants to be your best pal. Also he’s a genius, and probably, you figure from the start, psychotic in an as yet undetermined way. Isaac is, once again, dynamite.

He’s brought Caleb to his secret lair to see his new creation: a sexy robot lady, Ava (Alicia Vikander), who may or may not have achieved human-style sentience. It’s up to Caleb to perform a kind of Turing test on her, to interview her and decide if she’s passed. The movie is broken up by seven title cards, “Ava: Session 1,” and so on, during which sessions Caleb chats with Ava, seperated by a glass partition. She’s not allowed to leave her rooms.

Futuristic as Nathan’s compound is, it suffers daily power outages, during which his closed circuit camera system shuts off. When one occurs during Session 2, Ava tells Caleb that everything Nathan says is a lie.

Much of the movie works based on our not knowing who’s playing whom. Is Ava scheming against Nathan? Is Nathan scheming against Caleb? Is Caleb a pawn, or is he smart enough to find himself in the driver’s seat? It’s a carefully paced movie, not fast or flashy, but with a mounting tension you know is going to result in something weird happening.

What’s less exciting is when what happens happens. By which time I’d ceased to care much for any of these three characters. Does Garland care about any of them? I’m not sure.

Vikander plays the robot, Ava, as a creature making every effort to be human. Her movements are too smooth, too graceful. It’s an impressive performance, but I never felt empathy for the character. She’s a robot, after all. Caleb’s mission is the same as the audience’s: to decide whether she’s in fact conscious, or merely simulating consciousness (whether there’s any difference between the two isn’t discussed).

Ava isn’t the only robot Nathan’s ever built. She’s the latest model. He has a silent assistant, another beautiful woman, Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuna), who must, one thinks the first time she appears, also be a robot. Was I ever supposed to think otherwise?

Garland is interested in gender roles in Ex Machina, but this feels like another unexamined topic. Here we have a woman (or two, or…) trapped in her pretty cage by an overbearing man, and here comes a sweet boy-man who falls for her and wants to set her free, and isn’t this just another case of two male clichés deciding the fate of a woman? A woman whose parts are interchangeable with every other woman on display?

I mean there’s a metaphor screaming at one in the face here, yet the movie doesn’t really act on it. Ambiguity is a good thing, and Ex Machina is certainly ambiguous. What’s it about? What does it want to say? Which character should I be rooting for? Yet something about its ambiguity feels off-putting and confused, as though Garland likewise has no answers, as if he figures that just by touching on topics and throwing ambiguous characters at us, depth will be achieved.

By the end I didn’t care about anyone and didn’t buy their actions.

Yet I still enjoyed much of the movie. It’s got a nice look and an eerie vibe, and I like smart sci-fi. Even when it turns dumb.

There is more to say, but it resides below, in a world chock full of SPOILERS. Join me once you’ve seen Ex Machina, and we’ll stuff the comments section with more spoilers still.

BEWARE: HERE THERE BE SPOILERS

Let’s start with the end. What am I supposed to think of Ava? Maybe Garland wants me to be conflicted, but what’s strange is the movie is played as though the hero were escaping to freedom. We follow Ava, gazing joyfully on the world of colors revealed. Yet she’s an amoral, psychotic, murderous robot. I was not rooting for her.

I never bought that she was conscious. I feel like Garland was relying on her actually human eyes to make me like her, or else relying on the genre, and how we’re supposed to root for the experimentee who of course is sentient and just as human as a human.

But he didn’t bring me there. Ava never shows any depth of character. She acts the same as a chess program. Her goal is to seduce Caleb into freeing her, and so she does. Once free, she ditches him without a thought. Because she has no thoughts. She’s a computer.

If the movie is meant to show her brilliance in fooling both men, it likewise fails. She never tricks Nathan. He knows what she’s up to from the start. Caleb tricks Nathan. Ava gets lucky. A lesser guy wouldn’t have managed to pull a fast one on Nathan.

As for Nathan, of course he’s written to be the madman playing god, which in a Dr. Moreau-like scenario, sure, we’d judge him harshly. But creepy and messed up as he obviously is, he’s just making robots. Making them into hotties with realistic flesh is what’s disturbing (that and the fact that he’s making creepy realistic sentient sexbots to screw and/or dismantle in the first place, of course). Would we feel as concerned for Ava’s “life” if she were a black cube on a desktop?

This is another way the movie feels unfocused. Does it or does it not have something to say about women vis-à-vis men? Is Ava a woman, either literally or metaphorically? Or is it the question of A.I. that’s at issue, and how we should treat non-gendered, human-minded computers? The movie feels like a swirl of topics brought up, with none expanded on.

By the end, Nathan seems like the sanest character of the bunch. He knows these robots are trouble, he knows he’s got to be careful, and he is, until the plot requires him not to be. Given the genre of the movie, it certainly seems to me like I was supposed to be thinking, “Yeah, die, you god-playing monster!,” but I wasn’t.

Caleb is a pretty dodgy character, too. Ava tells him Nathan’s a liar during their second session. Already we’re supposed to believe Caleb has fallen for her? Already he’s sure this isn’t just another part of the test? He lies to Nathan at dinner about it in a scene purely genre-based. It’s what the character is supposed to do in this scene, in this movie. But it’s unearned. He should have told Nathan exactly what she said. The mind games would have taken a deeper, stranger turn if he had.

Nearer the end, what’s Caleb’s plan, anyway? To lock Nathan in his house, and run off to the helicopter with Ava? Then what? Sure, Nathan chose him special and all, but really? He falls so hard for the robot over six days he completely loses all sense of reality? If he’s so concerned for the sentient robots, why not just shut up, leave as scheduled, and tell the world what’s going on, NDA be damned?

I know. Because you wouldn’t have a movie. I just never bought his emotional journey. It feels placed upon him by a writer.

Why is Caleb locked inside the house at the end? We’re told he reprogrammed the system to open the doors during a power outage. At the end, there’s a power outage. The doors remain locked.

Finally there’s Ava, marveling at the world, soon to…to what? To murder people at will in her efforts to…um…fall in love? Reproduce? Hope she doesn’t scuff her now irreplaceable skin?

I know, I know, it’s all a beatiful allegory for…wait…for…female freedom? From oppressive men?

For life finding a way no matter the odds?

For the evils of “playing god”?

For scientists being bad people we should destroy?

For the human mind being nothing but an advanced computer?

I don’t know. Maybe it’s just a creepy movie.

Yarp. I feel much the same. Ava ran off and I thought… “wait! don’t forget your extra batteries…. nooooo!!!”

But as slovenly as the finish is, it makes me wonder whether Garland intended us not to ask about Ava, but about Caleb and Nathan.

Are they human? What does it really mean to be human? And why would anyone want that in the first place? Which those are interesting questions that my brain may have supplied in the absence of other interesting questions or which may be embedded in the film. Can’t say.

And that dance party. If that isn’t the equivalent of an origami unicorn I don’t know what is. I was vastly disappointed that Nathan didn’t turn out to be a robot or Caleb didn’t turn out to be a robot. And that there were a bunch of naked ladies hanging in the closet and that Nathan tried to stop his robot slaves with a metal stick.

I suppose I liked it, and am glad I saw it, but it wasn’t nearly as thought-provoking as I’d hoped. I’d say it wasn’t as good a film as Moon, but a better script than Sunshine, which just totally eats dirt at the end.

Yep, more sensible than Sunshine, for sure, yet with essentially the same ending he gives every story. I did like that Caleb at least considered the possibility that he himself was a robot. Though if it was me, I might have sliced a less bleedy part of me to find out.

As to who Garland wants us to wonder about, I still don’t know. I’ve read a few interviews with him today, and aside from coming off as simultaneously defensive/aggressive, his notions of what he’s making a movie about seem as muddled as the movie. I think he likes to provoke–“let’s hang naked female robot parts in specially designed closets in his bedroom! That’ll piss SOMEBODY off!”–purely for the sake of provoking.