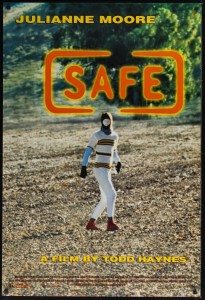

My recollection of Safe, Todd Haynes’s 1995 film about a woman suffering a mysterious environmental illness, from when I saw it once twenty years ago, is that I liked the creepy, unsettling first half, and didn’t like the slow, healing second half. At the time, I shrugged the movie off as interesting but unsuccessful.

My recollection of Safe, Todd Haynes’s 1995 film about a woman suffering a mysterious environmental illness, from when I saw it once twenty years ago, is that I liked the creepy, unsettling first half, and didn’t like the slow, healing second half. At the time, I shrugged the movie off as interesting but unsuccessful.

Upon finally watching it again, I realize I made the same boneheaded error many (but certainly not all) viewers did at the time: I read the ending as a positive one. Not quite upbeat, but one full of bland hope.

Safe does not have a hopeful ending. Rather its ending is exactly like its beginning: empty, lonely, bleak, and hopeless. The ending brings the character of Carol (Julianne Moore, at her best) full circle to where she began.

Carol begins the film trapped in her life of relative luxury in L.A.’s San Fernando Valley. The opening scene is shot from within her car, driving the evening streets of her wealthy neighborhood. The next scene is her on her back, her husband humping away furiously. Carol is not connected to anyone or anything, with the possible exception of the furniture.

Haynes said the look of the film was inspired by Kubrick, specifically 2001, with its clean, precise interiors. The people in Safe are often shot at a distance, with few close-ups. Carol herself is framed as a piece of the background—a lamp, a sofa, a Carol.

No information is provided us about her. She exists. And for Carol herself, this is all she does. But something is creeping into her life. Something is making her pay attention. At first it’s hard to put her finger on. She feels tired out, weak. She coughs, sneezes, appears wan. She goes to her doctor. Her tells her he can find nothing wrong. Must be stress. She agrees that she’s been pushing herself too hard lately.

Only what, exactly, does she do? Go to the cleaners? Have lunch with a friend? She has no job. She has a ten-year-old stepson she has no interaction with. Her husband, Greg (Xander Berkeley), works all the time, and when he wants to have sex, she’s too tired and vaguely ill. Her life is full of nice objects, but is otherwise empty, as empty as Carol herself. She is connected to no one, least of all herself.

She grows worse. Her doctor is stumped. He suggests seeing a “specialist,” handing a business card to—Greg. This is something between the menfolk. “A psychiatrist?” asks Greg. Carol listens, silent.

She sees the psychiatrist, in an office cold, vast, inhuman. The man says little. Carol says little. Finally he asks her what’s going on inside. Carol stares, blank.

Haynes’s other major influence here is Douglas Sirk (whose films he paid more direct homage to in ’02 with Far From Heaven, also starring Moore). Colors are everywhere vibrant and lovingly lit. Everything is carefully arranged in every shot. Carol’s world is antiseptic. At least the interiors of it are. Outside, the world is choking on chemicals.

Carol sees a flyer at the hospital: “Are you allergic to the 20th century?” She goes to a meeting, where others like her are afflicted with ailments no one believes in. She goes to great lengths to protect herself. Eating carefully, eschewing makeup, wearing a mask when outside the house. It doesn’t help. She gets worse, winding up in the hospital. Yet her doctor continues to tell her he can find nothing wrong with her.

“It’s the chemicals!” cries Carol.

And it really is. Carol is actually sick in Safe. It’s the one thing she’s learned about herself. She is really and truly ill. And no one believes it’s real.

The first half of Safe is shot something like a horror movie. “Suburban horror,” it’s been called. Haynes may have been more inspired by The Shining than 2001. Long, static shots of rooms, close-ups of hair-dryers, eerie subtle music in the background. It all screams, “Something is coming to get you!”

The other genre Haynes riffs on is the disease-of-the-week movie. A character is happy, gets ill, faces terrible hardship, but in the end, overcomes it. This is Safe’s structure, yet the happy ending never arrives.

Carol sees an ad for a religious retreat in New Mexico called Wrenwood, founded by Peter (Peter Friedman), himself a sufferer not only of EI (“environmental illness”), but of AIDS as well.

Haynes set Safe in ’87 specifically to comment on the AIDS epidemic and the manner in which some popular writers urged those afflicted to essentially blame themselves for their weakened immune systems. But the movie might work even better now than it did in ’95, when AIDS was still a hot topic, in that the sickness faced by Carol and others isn’t a stand-in for anything specific. The movie ends up making a more general statement about affliction and the way it forces sufferers to come to terms with the connection between mind and body. In an oblique way, Haynes is getting at themes Cronenberg has spent his career exploring far more graphically.

Carol decides to spend a month in the healing, chemical-free zone of the Wrenwood retreat. This section of the movie is at first confusing. Soon-to-be-Mrs. The Supreme Being had me pause the movie to ask how we were supposed to be interpreting scenes of patients explaining to Carol how good Wrenwood will be for her. At face value? As sly mockery? I said I’d been thinking exactly the same thing: that I couldn’t tell. Which struck me as good. It’s easy to make fun of new-age healers. Here was a movie showing them subtly enough to be unsure of the filmmaker’s intent.

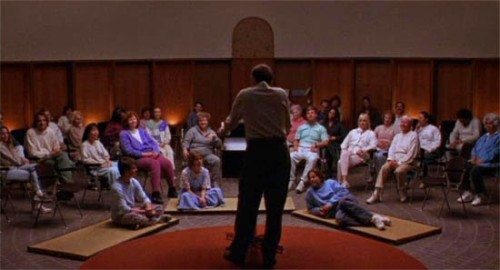

But soon the intent becomes clear. A shot of Peter’s giant house on the hillside overlooking the retreat tips Haynes’s hand. Followed by a telling scene in which Peter asks a number of patients to share what was going on in their lives when they first became sick. Peter explains to each of them that it’s what’s inside of them that’s causing their illness. They sob in gratitude. Yes, of course, it’s their own weaknesses destroying them.

And so Carol has come full circle. Her doctor and husband and friends think her sickness is all in her mind. The people at Wrenwood think it’s real, but that’s it her fault. Carol goes from one trap to another.

One patient’s husband built a small, domed safehouse with ceramic walls to keep everything out. He lived in it for years. Then he dies. What to do with his protective igloo? Maybe Carol, growing steadily worse, would like to live inside of it?

Carol’s journey takes her from lonely, disconnected isolation to lonely, disconnected isolation. Greg visits Wrenwood once, just before Carol moves in to the safehouse. She can’t hug him, maybe because of something he washed his shirt with? And away he goes.

I felt exceptionally unsettled by the end of Safe, so too did soon-to-be-Mrs. The Supreme Being. We had a hard time wrapping our heads around what the movie meant to say about illness and healing and self-blame. Took us a day of thinking and talking to come to terms with it. Reading a few old interviews with Haynes shed some light on it, too, in terms of where he was coming from in making it. But once my brain had settled some, Safe seemed to make a very precise kind of sense.

The strangest image in Safe is that of a man dressed protectively at Wrenwood. He appears far away in just two scenes, walking as if he were some kind of mutant deer, skittish at the sight of humans. He’s like a vision from our future, one to which we’re all allergic.