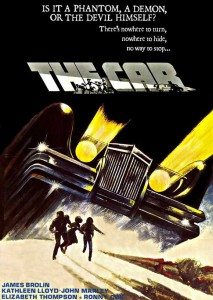

I’m not afraid to say it, despite the mysterious winds suddenly whipping, despite the distant sound of an engine revving, despite the flames on the horizon, no, I’ll say it anyway: The Car, the 1977 Jaws rip-off about a demon car on the prowl, is actually kind of great. And not in a so-bad-it’s-good way. I mean it’s actually, legitimately kind of a great movie. Which I know, I’m still hedging with the “kind of,” because no, it’s not Jaws. Few movies are. On the other hand, it’s not Duel, either, and I mean that in a good way. Duel is the other Spielberg flick inspiring The Car (not to mention inspiring Jaws itself), and I never thought much of Duel, in which a trucker—his face never seen—terrorizes a regular guy on a desert highway. As a TV movie originally, I bet it worked better broken up by commercials. Watched as a movie, it plays like a 50 minute TV show dragged out to 90 minutes. There’s 50 minutes of creepy, well-shot action in Duel, and then another 40 minutes killing time.

I’m not afraid to say it, despite the mysterious winds suddenly whipping, despite the distant sound of an engine revving, despite the flames on the horizon, no, I’ll say it anyway: The Car, the 1977 Jaws rip-off about a demon car on the prowl, is actually kind of great. And not in a so-bad-it’s-good way. I mean it’s actually, legitimately kind of a great movie. Which I know, I’m still hedging with the “kind of,” because no, it’s not Jaws. Few movies are. On the other hand, it’s not Duel, either, and I mean that in a good way. Duel is the other Spielberg flick inspiring The Car (not to mention inspiring Jaws itself), and I never thought much of Duel, in which a trucker—his face never seen—terrorizes a regular guy on a desert highway. As a TV movie originally, I bet it worked better broken up by commercials. Watched as a movie, it plays like a 50 minute TV show dragged out to 90 minutes. There’s 50 minutes of creepy, well-shot action in Duel, and then another 40 minutes killing time.

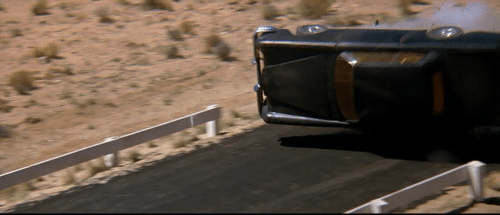

The Car is not dragged out for 97 minutes. It is almost non-stop action. Best of all, I think, and the reason, I suspect, it was easy to pan when it came out (which it was; it did not go over well in ’77), is how completely straight it’s played. There is nothing tongue-in-cheek about the seemingly driverless, black 1971 Lincoln Continental Mark III appearing one morning from the depths of the Utah desert to terrorize the small town of Santa Ynez. It just appears. And attacks. And kills.

And in so doing, it’s kind of great.

There’s no reason for the Car to be attacking this particular town, any more than there was a reason for the shark to attack Amity, beyond, simply, “food.” There is food here. And the Car is hungry.

It opens with a quote from, naturally, Anton LeVay’s The Satanic Bible: “Oh great brothers of the night who rideth upon the hot winds of Hell, who dwelleth in the Devil’s lair; move and appear.”

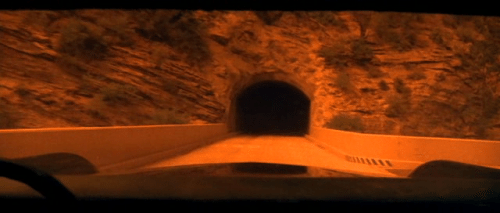

A shot of the empty desert, the sun rising. A line of dust rising in the morning light. The Car is coming. Cut to a girl and her guy riding bicycles on the highway across high desert cliffs. And then? Oh yes—cut to Car-vision! A reddish-orange POV from within the Car! You know what happens next. Biker death.

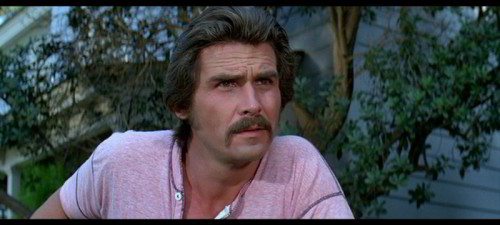

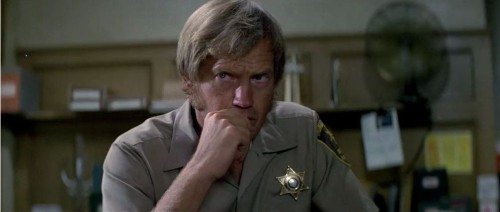

Our heroes are local cop, Wade Parent (James Brolin), and his young, schoolteacher girlfriend, Lauren (Kathleen Lloyd). What begins for them as a frolicsome day in bed turns into something from their nightmares. Well. Assuming they’ve been dreaming of death by demoncar.

The cops are stumped. Amos, an old wife-beating son-of-a-bitch, saw the Car run down a hitchhiker, but doesn’t remember what the Car looked like. Next the Car comes for the chief of police, and when it does, an old Indian lady sees the attack. She describes it to the Indian deputy, but says something he doesn’t translate. We later learn what it was she said: the Car had no driver.

Cue dramatic music. Speaking of which, woven extensively into the music is the Dies Irae, the famous eight-note Gregorian chant you know best from its extensive use as the theme in The Shining. Am I saying Kubrick ripped off The Car to score The Shining? Why not? What’s Kubrick gonna do? Sue me? [Note to Kubrick estate: please do not sue me.]

Did Stephen King rip of The Car for his novel Christine? Well, maybe. On the other hand, King is obsessed with motor vehicles, demon-haunted and otherwise, so maybe not. In terms of a double feature, you could do a lot worse in life than pairing The Car with John Carpenter’s Christine (’83).

Where were we? So the Car is killing people left and right and what’s this? Deputy Luke (Ronny Cox) forgot to tell the school not have parade practice today? Damn! An unfortunate oversight. Thing is, Luke is actually a great character, one rarely seen in any movies of this kind. He’s genuinely affected by four murders in a single day. His world has been shaken. He sneaks out to his car for a long pull of whiskey. He hangs his head, his mind faraway, barely able to talk or move. He’s a mess, in a way most of us would be if a strange car had run down four people in our small town, in a way movie characters rarely are. I liked that.

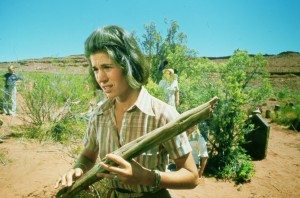

So the parade practice. Out on a wide dirt road by the stables. Best of all is there’s this high sort of platform, almost like—wait for it—a lifeguard post, up which climbs a cop, acting one supposes as a demoncar spotter. In one lovely shot, the cop is in the foreground on one side of the screen, the distant desert in the other. There’s a flash in the desert, so quick I wasn’t sure I’d seen it. Cut to the paraders. Cut back to the cop. Another flash, and another—sun glinting off an unseen windshield. It’s coming!

It’s this scene that really gets to the heart of what I liked about The Car. On the face of it, it’s absurd. It’s purposefully reminiscent of the crowded beach attack in Jaws, complete with a lifeguard perch and the Car zipping along the crest of a ridge such that only the very top of its roof is visible, rather like a shark fin. Yet it’s shot and edited and acted in every way as seriously as the kind of movie people tend to take much more seriously than this one. It sells its absurdity with sincerity.

Which brings me to the direction, by veteran TV director Elliot Silverstein (best known for the ’65 Jane Fonda/Lee Marvin comic western, Cat Ballou). He does a great job. However trashy one may decide this movie is, it’s directed with genuine style and intelligence. Not a flashy style, mind you. More in that it’s just solid all the way through, with some minor beautiful touches throughout. Like the scene where Lauren’s on the phone in her living room at night, telling Wade that the wind is up and she hears an engine. She’s to one side of the frame in the foreground. Dead-center of the frame, behind her, is her wide living room window, the dark of night outside. A tiny light appears far in the distance. The light grows larger, splits into two lights—headlights—coming right for her. But she’s facing away, talking on the phone. Turn around, you fool!

What happens next you will enjoy very much.

The Car itself is shot like it’s an animal. It has personality. It’s smart. It corners its prey, toys with them, before killing them. At times, as when Wade finds it waiting for him inside his own garage, it is totally still, waiting to strike.

How to kill a demoncar? Good question. When the cops shoot it, the bullets not only have no effect, they seem to vanish before making contact. The Car is impervious. Nevertheless, a plan, an outrageous plan, is put into effect with unlikely precision and speed, and the finale of this movie, well, it’s not one expects to see. In short, the Car’s demonic origins will be forever burned into your retinas.

I didn’t know what to expect of The Car. I figured it’d be about as high quality as Frogs, which I watched recently, a genuine piece of dopey ‘70s trash. In part enjoyable, but as trashy as trash can be. The Car is suprisingly different. I love how sincerely it takes itself. It’s a real movie, is what it is. A real movie about the devil in the form of a Lincoln Continental terrorizing humanity. What’s not to love?

I think I would rather watch The Car than work today. Is that an option?

More like a requirement.

It’s an interesting movie. As you say, it takes itself seriously and the carnage that the car inflicts feels very real because of that sincerity. The “demonic possession” seems a bit silly now, and likely did even in ’77 as it had become a bit passe’ by then. We were now all becoming entranced by Close Encounters and Galaxies Far, Far Away and the devil had had his day (except for a brief stop in Amityville a few years later).

I’d say it must have seemed sillier in ’77, hence it not faring well. It must have seemed like a particularly incomprehensible Jaws knockoff.

I watched it again a couple of months ago, and the sincerity really sells it. It works because nothing is explained. It just IS. A demon car is attacking, like they do, and by gosh it has to be stopped.

A) Yes. And the score. Wow.

B) You didn’t tell me this was a prequel to No Country for Old Men. I do believe that is double feature right there. Yep. Sure is.

SB4MCDF #110: Brolins vs. Inexplicable Evil in the American Southwest