Mongrel monster movie White God (Fehér isten) wants to have its kibble and eat it too. Part political allegory, part melodramatic coming-of-age affair, and part Rise of the Planet of the Apes with dogs, this Hungarian picture — a Cannes Un Prize du Certain Regard winner — left me with heartworm. Worms, in my heart.

Mongrel monster movie White God (Fehér isten) wants to have its kibble and eat it too. Part political allegory, part melodramatic coming-of-age affair, and part Rise of the Planet of the Apes with dogs, this Hungarian picture — a Cannes Un Prize du Certain Regard winner — left me with heartworm. Worms, in my heart.

I was also dragging my butt around on the carpet but I can’t solely blame the film for that.

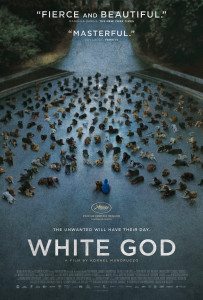

White God entices with powerful imagery and ideas at least. It is marketed as a strange fable: unwanted mutts throw off the collars of control and, along with a pubescent girl, claim the city as their own. That is, indeed, part of the film — and the political part. Writer/director Kornél Mundruczó obliquely frames his mongrels, including our mixed-breed protagonist Hagen, as the unwanted others, i.e. immigrants.

Hagen is the adored pet of Lili (Zsófia Psotta), and that makes fine sense. Dogs are loveable, particularly the mutts. I expect many people who choose to see White God will likewise love dogs and this as you’ll see proves problematic.

At the start of the film Lili’s mother heads off to Australia for three months, leaving her daughter with her ex-husband, Dániel (Sándor Zsótér). Dániel is a prick. He is the sort of father who doesn’t realize that his daughter has a dog and who is disinclined to take the animal in. Then again, Lili’s mother is also sort of a prick, as she’s the sort of mother who doesn’t bother to make any real arrangements for her daughter (or her dog) before going overseas for three months. This awkward cruelty infests the film in a way that may make fairy tale sense, but which certain doesn’t give the story heft or you incentive to invest in the characters.

Lili’s father gets reported for housing a mixed-breed dog — something vaguely criminal in the film’s unreal reality — and refuses to pay the tax for Hagen. Instead, when Lili behaves as thirteen year olds behave, Dániel grabs Hagen by his scruff and leaves him by the side of the road. The poor dog, abandoned, spends much of the rest of the film attempting to survive the viciousness of human society.

For those that love dogs — like me — watching some of this violence will be difficult. No animals were harmed in the making of White God, but that’s not how it comes across. And that’s the first challenge of the film. What non-dog lover wants to watch a film about dogs?; and what dog lover wants to watch a film about animal abuse?

It’s an infestation of heartworm, right?

What if, however, the dogs (i.e. immigrants) find themselves so traumatized by their treatment that they gain the super-canine wherewithal to form an organized mob and seek vengeance?

What if, however, the dogs (i.e. immigrants) find themselves so traumatized by their treatment that they gain the super-canine wherewithal to form an organized mob and seek vengeance?

I don’t have the answer to that question; I’m asking you. And I’ve seen White God.

As Hagen survives dog fights and dog catchers and dog pounds, Lili first tries to find her pet and then doesn’t. Spanning months, Hagen’s story is mirrored by scene after scene of Lili being a teenager. She goes to parties. She gets snotty with her teacher. She develops a relationship with her father.

She bores me to tears.

Try as I might, I cannot see any connection between Lili’s half of White God and Hagen’s. When the dogs revolt under the leadership of Hagan — and that’s the premise of the film, not a spoiler — Lili extrapolates from no data that she is the cause and object of the rebellion.

In the vague cypher of the film, Lili, perhaps representing the innocent of heart and action among us, could be correct. The violence to and of immigrants might be stemmed if we only bothered to include and respect them, as Lili does, then doesn’t, then risks her safety to once again do. If only we stepped up to our prick of a father and demanded we be allowed to keep our dog.

So, read that way, White God is a call to arms, or paws, or whatever you’ve got handy. Lili is the white god of the title and it is the power of her affection and acceptance that will save us.

Seems a bit facile to me.

Mundruczó can’t seem to quite decide whether we deserve to have our throats torn out or our faces licked and his ending makes that abundantly clear. He fails to maintain the fervor of his lack of conviction, softening our resolve with his loosey-goosey tangents with Lili, and then trying to force harsh reality into a fantastically shaped box.

In Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Caeser (Andy Serkis) gets a science-fictional solution that bestows upon him unworldly intelligence. When Caeser’s revolution kicks off, and there is suddenly an army of primates on the rampage in San Francisco, many asked: really? Where did all these apes come from? In White God there is no science-fiction and only occasional forays into parable. Hagen’s jailbreak results in hundreds of dogs overtaking the city streets, but without the science-fiction, the level of terror and the masses of animals here make as much sense as Jaws: The Revenge.

The political allegory is interesting, but unwieldy and ultimately unmoving. White God manages some fine imagery amid its excessive handheld cinematography, but mostly feels unfocused. Characters, including that of Hagen, can’t decide if they want to feel real or symbolic and so get lost in a muddy netherworld.

What would happen if immigrants — or animals — started a revolution? The thought is powerful and frightening. White God dares to ask the question and cleverly stages the scene, but then, in the end, leaves you dragging your butt across the carpet trying to rid yourself of the itch to answer.