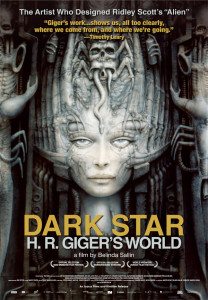

H.R. Giger, who most famously created the monster design for Alien (and less famously, prior to that, artwork for Jodorowsky’s never-made Dune adaptation), is a pleasant old man at the end of his life in the new documentary, Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World, much of which follows Giger, his wife, and friends puttering around his cluttered home of many years.

H.R. Giger, who most famously created the monster design for Alien (and less famously, prior to that, artwork for Jodorowsky’s never-made Dune adaptation), is a pleasant old man at the end of his life in the new documentary, Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World, much of which follows Giger, his wife, and friends puttering around his cluttered home of many years.

Dark Star is a nicely puttering little movie, refreshingly unlike so many modern docs, those that consist largely of talking heads speedily edited together with rapid-fire clips, so as not to bore audiences. Defensive movie-making, this is called. It’s assumed documentaries bore people, so they’re now edited as jauntily as possible, to keep things moving. Dark Star has very few people sitting down for proper interviews. There are a few, scattered throughout, but they’re not there to relate Giger’s history. Instead they talk about him as a man and as an artist, or talk about his art, or about how he and his atwork affected their lives.

No chronological story is told here. A certain amount of old footage is included of Giger as a younger man, but there’s no narration over it. It’s more that Dark Star, a Swiss production directed by Belinda Sallin, gives an impression of Giger’s life and work, and does so in a gently paced, meandering way. Which style I liked quite a bit. By its nature it was slow to grow on me, but the more I watched, the more the picture was filled in, and the more I became absorbed in it.

At one point I began wishing they’d just show more of his artwork up close, instead of showing shaky shots of it hanging on the walls of his house—and almost as if reading my mind, the movie went into a section showing off his artwork. Well played, Dark Star, well played.

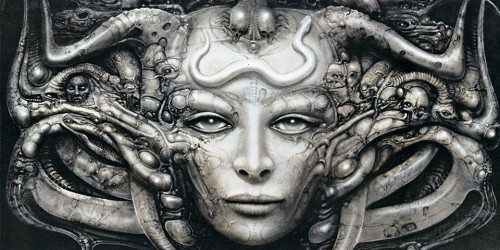

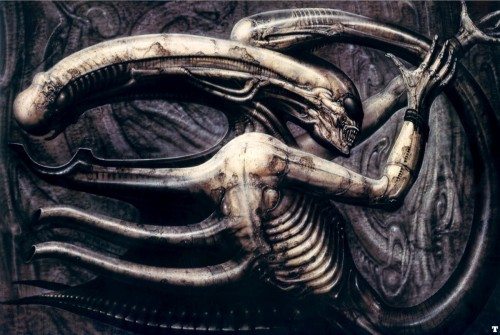

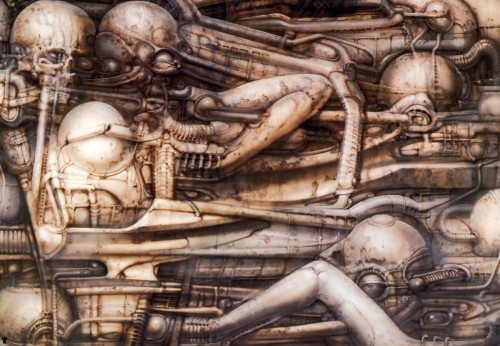

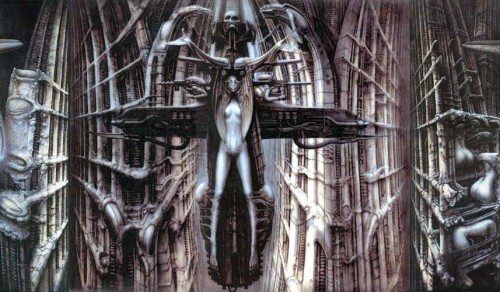

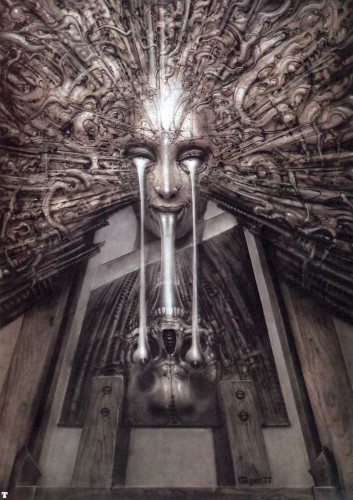

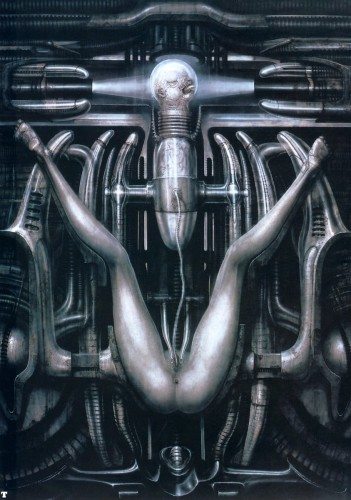

Giger’s art is generally described as being “biomechanoid,” or some other made up word like that. One thing’s for sure: it’s unique. Nobody paints like Giger. Once you’ve seen anything he’s done, and you have, because you love Alien and like me have watched it 500 times, his work, any of it, is instantly recognizeable. It’s all women and bones and machines and warped little children, birth and sex and death, all in the same painting, all happening at the same time.

Well. I’m not going to try to describe his art. Look for yourself. Whatever, exactly, it is, it sticks its fingers deep inside the human psyche and wriggles them around.

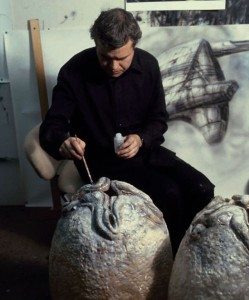

A small part of the movie focuses on Alien, with some nice footage of Giger constructing the space-jockey set, and an old interview where he explains that his original alien egg opening—a slit—looked too much like a vagina. “This movie is going to play in Catholic countries,” he was told, so he had to make it less sexual. His solution? Two crossing slits, i.e., two vaginas in the shape of a cross. Take that, Catholics!

There’s no mention of Giger’s earlier, unused work for Jodorowsky’s unrealized Dune project, but again, this isn’t a comprehensive look at Giger. It’s a meandering one. Eventually it meanders to a little Swiss town where Giger grew up. His mother, it turns out, was a huge supporter of his art, though initially Giger worried—as one might expect—about what reaction his parents would have to the things he painted.

Giger spent most the money his art brought in on still other creations. Like the kid-sized, haunted house-like train set in his backyard, which we get to ride around on. Also toward the end of his life, he participated in the creation of a Giger museum in Switzerland to house a large portion of his work, much of which he’d slowly bought back from collectors over the years. For the museum’s opening, Giger signs books and posters and body parts. One of his male fans pulls off his shirt and turns around to reveal his entire back tattooed with one of Giger’s images. “Very nice work,” mutters Giger. One tough-looking, tattooed young man has his art signed, shakes Giger’s hand, and walks away crying. Giger’s work had a profound effect on many people.

Giger died in 2014, shortly after the completion of Dark Star. He does look a bit like he’s near his end while being interviewed. He doesn’t have a lot to say. What comes across clearly is a man who’s satisfied with his work, who got to do exactly what he wanted, who didn’t feel he’d failed to accomplish anything he set out to accomplish.