George Miller is back with Mad Max: Fury Road, the first Mad Max movie in 30 years, and I can’t believe I have to wait another two days to see it, but so it goes. Word is it doesn’t suck. No doubt I will report back on the matter shortly (two days!), but in the meantime I re-watched the original trilogy in preparation. And loved it. I didn’t love all its parts equally, but as a whole it’s a magnificently bizarre trilogy of movies. It doesn’t play like typical sequels play. It’s almost like watching three movies in different genres, with one character drifting through each of them.

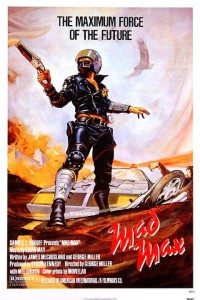

Mad Max (’79) opens with the legend “A few years from now,” and though law and order has clearly broken down, there’s little else to indicate a post-apocalyptic world as we typically imagine it. Mel Gibson, an unknown in his second movie, plays Max Rockatansky, the best of the best among a new breed of cops, the go-to man to chase down the wild lunatics taking over the roads.

Mad Max (’79) opens with the legend “A few years from now,” and though law and order has clearly broken down, there’s little else to indicate a post-apocalyptic world as we typically imagine it. Mel Gibson, an unknown in his second movie, plays Max Rockatansky, the best of the best among a new breed of cops, the go-to man to chase down the wild lunatics taking over the roads.

It’s a slow burn of a movie, at least in the emotional sense. It’s the story of Max, good cop and family man, being slowly broken down and hollowed out by the state of the world.

An evil motorcycle gang led by The Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne, who returns to the Mad Max world as the heavy in Fury Road) is out there terrorizing people, and when Toecutter’s protégé, Johnny The Boy (Tim Burns), is arrested by Max and his partner, Goose (Steve Bisley), and is then let off by the court, trouble’s in store.

Toecutter’s gang burns Goose to a crisp (wait, they cook his goose? Har har), leaving Max to wonder if he’s next. He quits the police force and goes on holiday with the family to think about his future, when who should turn up but Toecutter and the boys, who manage to track Max to the coast.

The bikers kill Max’s wife and baby son, run them down in the middle of the road. So Max seeks revenge, becoming more cruel, angry, and driven the further he plunges into the darkness of killing.

The final scene is Max, expressionless, driving away from the explosion killing Johnny, the last of the gang.

The kind of widescreen, low to the ground shots of the road Miller would perfect in Mad Max 2 (AKA The Road Warrior) are in evidence throughout Mad Max. The feeling of speed is palpable. Speed and danger. These cars are going fast. There are no special effects, outside of massive explosions and car crashes.

The movie has been described as a kind of western in terms of plot and character. A wronged man seeks revenge in a world gone cold. It’s a story as old as time (which what does that say about the state of the human-centered world? That at any given time, in every culture, it’s perceived as becoming more cruel and lonely and heartless?). Mad Max was a hit all over the world (less so in the U.S., where it was barely released, and with all the Australian actors’ voices dubbed by Americans), and Miller realized the reason was that, unintentionally, he’d hit upon a fundamental character every culture was able to fit into their story-telling heritage.

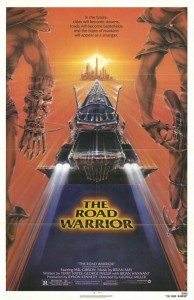

For the sequel, Miller decided to make a myth on purpose. He read Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces, an anthropological amalgamation of hero myths across time and cultures, watched movies like Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, and created The Road Warrior (so-named only in the U.S., but come on, how great a title is that? Considerably more inspiring than Mad Max 2).

Though it’s a continuation of Max’s story, The Road Warrior (’81) works as a stand-alone film. It opens with newsreel footage in a square aspect ratio showing the collapse of the world, narrated by an unidentified narrator. A brief series of shots from Mad Max are included, and finally we swoop down over the desert, the screen cuts to black, then cuts to a widescreen close-up of Max driving, essentially copying the final shot from the first film. And we’re off!

Though it’s a continuation of Max’s story, The Road Warrior (’81) works as a stand-alone film. It opens with newsreel footage in a square aspect ratio showing the collapse of the world, narrated by an unidentified narrator. A brief series of shots from Mad Max are included, and finally we swoop down over the desert, the screen cuts to black, then cuts to a widescreen close-up of Max driving, essentially copying the final shot from the first film. And we’re off!

As I wrote some time ago, The Road Warrior is the best action movie of the ‘80s. But that was for an article focusing on the ‘80s. I will here say that it’s the best action movie, period. So there. It’s also the best comic book movie, though it’s not based on a comic book. It’s told with barely any dialogue. It’s a movie in the purest sense, told though the juxtaposition of images. The editing is beautiful. There is not a single wasted frame.

And the story is perfectly simple. A lesson current movie-makers might well pay attention to. You don’t need hours of complicated plot and back-story to make a thrilling movie. You just need a compelling character doing things.

When people today think “post-apocalyptic,” they are almost certainly picturing a wasted desert landscape peopled by punky, mohawked, leather-clad biker gangs. All this we owe The Road Warrior. Miller not only tapped into myth for his character and story, but somehow in creating his desert hellscape he tapped into a shared visual representation of our collective unconscious fear of a future laid waste by nuclear war. To be fair, A Boy And His Dog (’75) got the ball rolling, but Miller added an outsized style to his desert wasteland.

The Road Warrior wastes no time. It opens with Max chased by The Humungus’s henchman, Wez (Vernon Wells), which chase ends at the site of a crashed semi-truck (a fateful truck, it turns out). In the next scene Max meets the Gyro Captain (Bruce Spence), who tells him about a group of survivors pumping gas.

Max finds a way in, encounters the Humungus, makes a deal to fetch the rig in exchance for gas, almost gets killed running away, makes it back alive, and, with nothing else left to him, signs on to drive the tanker. The tanker which, it will turn out, is only the decoy.

One moment I love is when Max first takes off with his gasoline, and the injured leader of the group, Pappagallo (Michael Preston), is asked by an underling who will drive the tanker now? Pappagallo says he’ll do it himself, but it seems such a heavy thing the way he says it. And one thinks, sure, The Humungus will attack. But won’t he attack everyone equally? Why so sad, Pappagallo? He’s sad, one learns by the end of the movie, because it’s a suicide mission; the tanker is full of sand. Too bad they weren’t able to sucker that Max guy into doing it. Best of all is how during the scene Pappagallo is idly turning over a small hourglass, watching the sand flow.

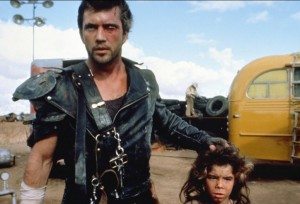

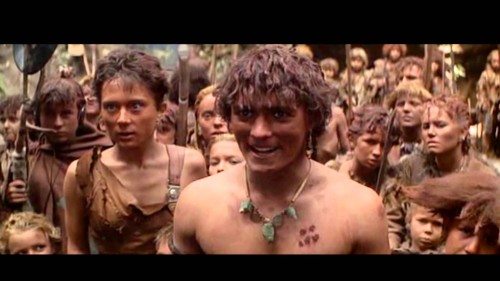

Max is the epitome of the burnt-out loner. He has no interest in going north with these people to whatever promised land they believe awaits. He almost connects with the Feral Kid (Emil Minty), gives him a little metal musicbox that plays “Happy Birthday,” but when the Kid tries to come along with Max, he won’t let him. Later, he stows away on the tanker. Max doesn’t agree to drive as a way to join these people. He doesn’t want a family. He’s got nothing left, so he might as well do something useful instead of rolling over and dying. If driving the truck kills him, so what? And if it doesn’t, well, so what again? When he succeeds and finds the truck filled with sand, he cracks his one and only smile.

In the end, the Feral Kid turns out to be the narrator. He becomes the leader of his people. But the Road Warrior doesn’t come with them. No mythic savior would. He’s cursed to roam the wastelands alone.

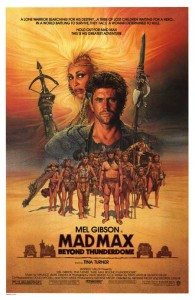

For Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (’85), Miller wanted to create some sense of hope in his world, so he brought in the children. Always a risky ploy.

I hadn’t seen Thunderdome since the ‘80s. I didn’t like it then. I liked it more this time around, but not because of the story as a whole. It’s a movie filled with wonderful pieces that don’t ever fit into a coherent whole.

It gets off to a grim start. Over the opening credits a dreadful ‘80s drumbeat starts, and all of a sudden we’re suffering through some godawful Tina Turner song. I can’t imagine what they were thinking. You don’t play the crappy end-credits pop song at the front of your movie, you bury it at the end! Oh, I see. There’s another crappy Turner song over the end credits. Egads.

But post-song we’re launched into the desert, and it looks great. Bruce Spence is back, this time flying a small plane, which actually rather confused me until I decided he couldn’t be the same character he played in The Road Warrior. And there’s Max, robbed of his car and his camels.

Only Max is no longer Max. He’s Mel Gibson. Something happened over these four years. Mel Gibson went from young actor with something to prove to, I guess, Mel Gibson. It’s something about the expression he wears, something smug and knowing. And his hair, good lord, the ‘80s, they were in their way a horrifying time to live through.

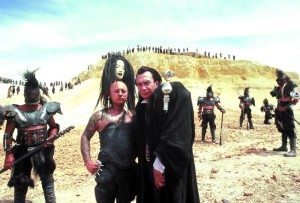

Max wanders into Bartertown, and already we’ve been brought into a world far removed from parts 1 and 2. The style of dress is the same as in the previous movie, but now there’s a whole town full of weirdos wearing it, each with their own flair. The details are what sell it. Nobody looks like a movie star. Everything is just strange enough to be plausible, or at least comic book plausible. My favorite character is Auntie Entity’s henchman, Ironbar Bassey (played by Angry Anderson, almost as brilliant a name as Emil Minty), a very short fellow who wears a pole strapped to his back atop which, above his head, is a scary doll’s face.

The look and feel of Bartertown reminded me of Miller’s other genius movie, Babe: Pig In The City, and so too the humor, a new element in the Mad Max series. There are some little funny moments in the earlier films—The Feral Kid’s boomerang slicing off The Toadie’s fingers comes to mind—but there’s a kind of gleeful humor underlying the entire Bartertown sequence. Sometimes it works, sometimes it’s just—odd .

Like Master Blaster, the dwarf on the back of the giant. I didn’t exactly like the character, but the imagination behind it is appealing. It fits in this world.

Thunderdome seems to be any number of movies jammed together. The Bartertown sequence is a long one. Plotwise, it functions to get Max banished to the desert to die, where he instead encounters a group of children living in peace at the site of a crashed jumbo jet. Their parents went to get help. They haven’t come back. They believe Max is the Pilot, returned to rescue them. Thematically, Bartertown exists to show one possible type of society, a violent, unforgiving one. The contrasting society comes at the end of the movie, with the children relocated to the ruins of Sydney and starting anew.

Max needs to be the thread tying everything together, but I found his character kind of blank and confused. His motivations are muddled. Half of the time he’s just doing a retread of what he did in The Road Warrior, and the other half he’s a selfless nice guy looking out for the wee ones. Thunderdome is set something like 15 years later than The Road Warrior, yet it feels like little thought was given to what Max was up to in the interim, or how it would have affected him. Worst of all, he’s strangely loquacious. He speaks more in the first 15 minutes than he does in all of The Road Warrior. A chatty Max is a bit jarring.

There’s one chase sequence in Thunderdome, which doesn’t play well compared to its predecessor, and then the movie ends with everyone off to start a new life and Max staying behind, having helped them on their way. Just like last time.

So in the case of Max’s character, Thunderdome functions exactly as a standard sequel—Max does exactly what he did before. But he does it in a very different kind of movie. Which makes it all the more a shame. There’s a fun, weird, imaginative movie in Thunderdome that’s killed by an emptiness at its core. Max needs to undergo a different change here. Or if the point is for Max never to change, he needs at least to do something different, or to have his actions result in a different outcome.

Tina Turner was Miller’s first choice to play Aunty Entity. He wrote the role with her in mind. She’s fine, I guess, though she’s not really an actor, is she? Mostly she sneers a lot. Also, she’s not evil. There is no real villian in the movie. Entity and her minions play the role of antagonists, especially once Max messes up Bartertown, but it’s never the case that Max is actively against them, as such. Which is another way in which the movie feels unfocused.

Part of the problem may well lie outside the bounds of the film. Byron Kennedy, producer of the first two films, and longtime friend of Miller’s, died in a helicopter crash in ’83. Miller considered not going ahead with Thunderdome, but eventually took it on, co-directing it with George Ogilvie. This may have led to the energy and focus of the first two films being dissipated.

The Thunderdome itself is a great movie invention. Like everything else in here, it’s almost too goofy to believe, but not quite. “Two men enter, one man leaves.” You can’t deny words of wisdom like those.

So what do we have here? We have, on the whole, a unique trilogy that defined the look of an imagined, doomed future, one imitated to this day. In its parts, we’ve got a well-made low-budget revenge flick, a timeless action masterpiece, and an imaginatively overstuffed yet emotionally empty curiosity. I can’t wait to see what’s next. I mean literally, I can’t wait. Two days? TWO DAYS?!? Sigh.

I followed your lead and had a back to back viewing of all three Mad Max films last night at home and tonight I am going to watch the new one at the cinema. Thanks for the great idea!

There are lots of things I realized when watching all three installments one after the other, but my observations will have to wait until I am back from the cinema tonight. Hope you had the chance in the meantime and are readying a review of Number Four for all of us! And now off to the Wastelands …