Watching Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck I often wanted to look away. It’s almost too personal, too intimate. It feels like an invasion of privacy, one committed only because the subject is famous, and one desired only because the subject is famous. But I watched it anyway. It’s fascinating. And incredibly sad.

Watching Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck I often wanted to look away. It’s almost too personal, too intimate. It feels like an invasion of privacy, one committed only because the subject is famous, and one desired only because the subject is famous. But I watched it anyway. It’s fascinating. And incredibly sad.

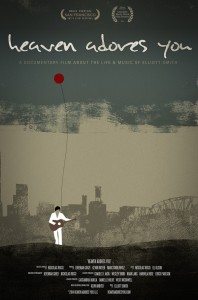

Watching Heaven Adores You, about Elliott Smith, I either wanted to fall asleep or scream at the dull talking heads on-screen to shut the fuck up so I could hear the music. Rarely have I seen a more distancing documentary. By the end I felt I knew less about Smith than when I went in.

Needless to say, these two docs couldn’t be more different. Brett Morgen, director of Montage of Heck, certainly had more access and more money to craft his tale, but money and access didn’t magically create Morgen’s artistry, imagination, and insight. Nickolas Rossi, director of Heaven Adores You, may not have been blessed with as much of a budget or as big a treasure trove of his subject’s home movies and personal notebooks, but neither was he blessed with the ability to tell a story.

Heaven Adores You is a documentary as Wikipedia entry. If you want the bullet points version of Elliott Smith’s life and career as delivered by a series of talking heads—ex-bandmates, ex-girlfriends, managers, etc.—this is the movie for you. If you want to understand anything at all about Smith, or be overwhelmed by the power of his music, you’re out of luck.

Heaven Adores You is a documentary as Wikipedia entry. If you want the bullet points version of Elliott Smith’s life and career as delivered by a series of talking heads—ex-bandmates, ex-girlfriends, managers, etc.—this is the movie for you. If you want to understand anything at all about Smith, or be overwhelmed by the power of his music, you’re out of luck.

This is a movie where talking heads tell us, at length, about the stunning, immediate power of Smith’s simple, one-man performances, without actually showing any. That’s not true. The movie shows some of these performances—there’s video—but without sound! All we hear is more tedious narration. The few times we actually get to see/hear Smith playing, it’s for no more than ten seconds before the sound is mixed down and some idiot starts bleating. It’s stunning. What were they thinking? The only songs played at any kind of length are album tracks. There’s simply no chance to sink into Smith’s music. The movie forces you out at every turn.

Morgen made Montage of Heck with the cooperation and encouragement of Cobain’s family and Courtney Love. Love gave him access to all of the old videotapes and notebooks and audio tapes Cobain made over the years, many of which no one, not even Love, had ever heard or seen.

Montage of Heck is a montage of a life. This is no historical document running through years and albums and dates. The interviewees are sparse, and include Love and Cobain’s parents and bandmates. People who knew him best. Though it’s structured from Cobain’s youth to his death, the movie doesn’t walk us through his life year by year. It glides around and inside and out, slowly painting a portrait of a kind, funny, and desperately sad man.

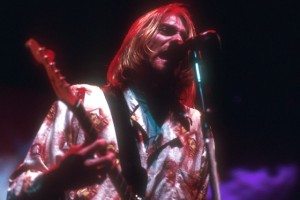

Aside from Nirvana’s Unplugged set, I’ve never been a big fan of their music, and only knew the basic media version of Cobain: a too-cool rocker who hated fame and killed himself when it got too hard to deal with. The truth is far more nuanced. It’s far more human.

Cobain yearned for fame, but not so much for the adulation or the money. He wanted to be loved. His family life as a kid was just terrible. Here was this sensitive, artistic kid pretty much pushed out of every home he had and into the arms of the underground music scene, and who, when finally he found the fame he’d sought, saw it was the last thing he needed. What he needed was a family. So he married Love and had a baby. And when he thought she’d cheated on him—she claims she never did—he tried to kill himself. A month later he tried again and succeeded. Cobain’s heroin addiction likely didn’t help his mental state any more than the fame or his shattered childhood. From an early age he wrote about suicide.

In many ways, Elliott Smith’s life charted a similar course. His childhood was marked by a broken family. As a teenager he abandoned Texas and moved to Portland where he fell into the punk scene. Unlike Cobain, Smith’s early punk bands didn’t launch him to worldwide fame. It was only later, when he began recording these sweet and sad songs by himself on acoustic guitar did he find an audience.

His audience grew slowly at first, but similar to Nirvana hitting it huge in an instant, Smith became famous overnight when his song on the Good Will Hunting soundtrack, “Miss Misery,” was nominated for an Oscar. He went on to perform it during the Oscars telecast. Unlike Cobain, Smith never yearned for fame. Nothing could have been worse for him.

Or so it seems, and so say the talking heads in the movie. But the more they talk, the less it seems they know a damn thing about him. No one seems to know Smith. One guy says Smith was incredibly giving of himself, that he could meet someone and make them feel like he was their best friend, only to vanish from their lives just as quickly. Were all of these people likewise duped?

I mean it feels like there’s a fascinating character here. An introspective, shy artist who covers up his insecurities by giving people the impression of openness and warmth. But such an interpretation is never pursued. Nothing is pursued by Rossi aside from a dull, factual narration of what Smith did and when and with whom. And more often than not, with music so quiet it’s invisible. The one interviewee who seems ready to supply something other than distanced adulation, his ex-girlfriend, is never given the chance.

Along with the footage of old performances, the wealth of home movies, the audio tapes, and the old photos, Montage of Heck uses animated sequences to tell its story, with Cobain narrating (from his tapes). Some of these sequences feel overly movie-ish, let’s say, like Morgen was trying too hard, but at least they’re directly dramatizing episodes from Cobain’s life. Smith’s life is a blank in Heaven Adores You. I am not exaggerating when I say that fifty percent of the movie consists of B-roll shots of Portland, New York, and Los Angeles, i.e. the cities in which Smith lived. Just random shots of cities. Not taken when he lived there. Modern day. Completely random shit. Half the movie—at least—is this nonsense. Another quarter is stuffed by faces of the interviewees, including, amazingly, some dude who owned a venue where Smith played sometimes. “I didn’t know him,” he says. Are you fucking kidding me? If Rossi had interviewed a cashier at the corner store where Elliott bought beer it wouldn’t have been out of place in here.

I came to Heaven Adores You a huge fan of Smith’s music. By the end of the movie I desperately wanted to listen to some. The movie never let me sink into a single song, a single performance. Montage of Heck parses out the music (early performances, practice sessions, Nirvana shows, etc.) with skill and reason, without overdoing the hits (for the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” segment, an odd, dreamy cover version is played over footage of the band shooting the video; only over the movie’s end credits is Nirvana’s version finally played).

Not to put too fine a point on it, but I hated Heaven Adores You. It feels like a fan of Smith’s wanted to make “a documentary” without the benefit of knowing how. It has no purpose, no direction, no sense of discovery. Worst of all, it’s boring.

Morgen went into Montage of Heck with a specific goal: to explore Kurt Cobain through his own words, writings, home movies, songs, and the memories of those who loved him. It’s a deeply personal, revealing portrait of a tortured soul. It’s how you go about making a movie.