Melbourne, 1983. An ordinary sort of bloke — one possessing an intellect untested — runs into a spot of bother. He gets coerced into smuggling a kilo of heroin, from Thailand back into Australia, within his digestive tract. He gets nabbed by the coppers at the border as inexorably as food turns to waste inside our intestines. Imprisoned, nature is left to take its course. The expectation being that the foul evidence eventually must be revealed.

Melbourne, 1983. An ordinary sort of bloke — one possessing an intellect untested — runs into a spot of bother. He gets coerced into smuggling a kilo of heroin, from Thailand back into Australia, within his digestive tract. He gets nabbed by the coppers at the border as inexorably as food turns to waste inside our intestines. Imprisoned, nature is left to take its course. The expectation being that the foul evidence eventually must be revealed.

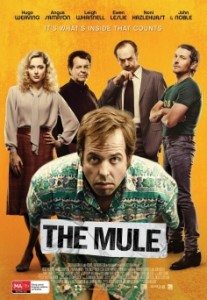

This is the story of The Mule, a 2014 film by first-time Aussie directors Tony Mahony and Angus Sampson. It is a film about compacted shit. It is about how if one can only retain and (sorry) reprocess one’s waste with enough force of will, in the end all that crap might end up gold. Or at least heroin, which is probably more valuable, at least dramatically.

Co-director Angus Sampson plays Ray, a television repairman, momma’s boy, footy player, and simpleton. His life of crime gets foisted upon him by those he loves, presumably because he’s naive enough to not say no. Sampson has a face and a (hopefully) affected demeanor that makes this acquiescence sadly believable. Less believable is why those of less virginal intellect would choose to involve Ray in such a delicate criminal enterprise. Or in anything more complicated that downing a beer.

And that’s more or less what there is in The Mule, a film I enjoyed in spurts. Ray finds himself guarded for an ever-increasing length of time by policemen played by Hugo Weaving and Ewan Leslie. They lock him in a hotel room with a colander bolted over the dunny and impatiently wait for him to void himself.

Ray does not comply, as compliance in this matter would equate to a confession.

Ray’s lawyer, played by the too fetching Georgina Haig, protects him from the rough justice the cops enjoy meting out. It is implied that she also feels more than platonic affection for him. This despite the fact that the man we’re speaking of is so full of shit he ought to explode. Other characters weave in and out in subplots of varying feasibility, interest, and humor.

So whether or not you will find something in The Mule to appreciate and enjoy depends largely on what you’re willing to swallow. And then how long you’ll hold onto it before relaxing your sphincter.

What charm the film possesses often gets sullied by scenes involving faeces. And then there is the question of whether you can sympathize or empathize with Ray and his predicament. The filmmakers add to this challenge by escalating the impact of Ray’s impacted state — not content with a poor bloke committed to staying corked up, they add police corruption, familial tragedy, and some light racism. The misogyny is limited to that evidenced, quite believably, by Weaving’s character.

The Mule is a film in which the hero’s journey is shorter than the number of steps from the bed to the toilet. His task is one we’re likely loathe to contemplate, let alone witness. It is a film about holding onto your shit, in every definition of the phrase. It is, in this regard, not un-clever. It is also, in this regard, limited in its appeal.

The Mule is a film in which the hero’s journey is shorter than the number of steps from the bed to the toilet. His task is one we’re likely loathe to contemplate, let alone witness. It is a film about holding onto your shit, in every definition of the phrase. It is, in this regard, not un-clever. It is also, in this regard, limited in its appeal.

There are sharp performances, and sly scenes, and moments of arch comedy. There are also plot twists that are hard to swallow, particularly after what you’ve watched people swallow on screen. Characters make an impression, but the world of the film remains erratic.

If The Mule had stuck to dark comedy, or committed to being a crime drama, it might have proved more compelling. Not doing so, it ends up leaving you with a pile of shit that might be worth something but only if you’re content to end up with your hands dirty.