If Tom Cruise were black, broke, and sliding around South Central Los Angeles in his tighty-whiteys then Rick Famuyiwa’s new film Dope might be mistaken for a remake of Risky Business. Remember that 1983 teen comedy? In it, a privileged suburban kid gets in over his head with sex professionals. He can only bail himself out — and get into Princeton — by making the best of a bad situation.

If Tom Cruise were black, broke, and sliding around South Central Los Angeles in his tighty-whiteys then Rick Famuyiwa’s new film Dope might be mistaken for a remake of Risky Business. Remember that 1983 teen comedy? In it, a privileged suburban kid gets in over his head with sex professionals. He can only bail himself out — and get into Princeton — by making the best of a bad situation.

Or, in the parlance of picture, by saying ‘what the fuck.’

‘What the fuck’ is a good question for Famuyiwa’s characters to ask, repeatedly, in Dope and also for us to ask of ourselves, after watching Dope. For while the film, which Famuyiwa both wrote and directed, lacks the devious precision of Paul Brickman’s surgical strike into 1980’s unbridled capitalism, it no less astutely impales the issues of our day. Issues, one might note depressingly, that haven’t shifted too far from those we were meant to have dealt with thirty years ago.

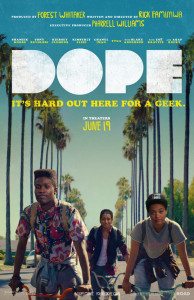

Dope focuses on Malcolm (Shameik Moore), a 1990s-era hip-hop obsessed geek doing his best to survive high school in his drug-infested, gang-ruled section of sunny L.A. Malcolm isn’t remotely close to being a stereotype, which is one of the film’s great strengths, but he also is constructed of characteristics more than he embodies character. That’s a fine distinction, but it’s an important one — and, as it turns out, a decision that wasn’t made unwittingly.

But at first, watching Dope unspool, I’m glad, for example, that Malcolm knows about technology and that he defies expectations for a man in his position. It’s just that his depiction, being so unusual, raises questions. This is a modern high school senior who dresses like Kid ‘n Play and who fronts for a pretty killer punk band? His only contact with his father came via a single greeting card and a VHS copy of Shaft? And that gun, is his timely possession of it more or less believable than the rest?

This is frequently how Dope goes; intriguingly but not so informatively — at least on a surface level. But we’ll get to that.

Malcolm runs around with Jib (Tony Revolori) and Diggy (Kiersey Clemons) — neither of whom get much chance to flash a ton of personality, but who play what they’ve got well enough that you almost don’t notice. Jib is a bit wussy and Diggy is a lesbian. That’s about it. The trio, improbably, end up at a local drug dealer’s birthday bash and even more improbably end up with a backpack full of narcotics. Thus encumbered, Malcolm attempts to dig himself out of danger, win the heart of a local girl (Zoë Kravitz, actually 27 years old), and gain admittance to Harvard.

All that should be an easy enough series of tasks for a teen comedy hero, except — if you hadn’t noticed or assumed — Malcolm is African American. And while some might avert their eyes from our country’s racial quagmire, Famuyiwa isn’t among them. So: Risky Business, but with a black lead stuck in a rough neighborhood, trying to survive not the underworld he’s stumbled into, but the underworld he’s expected to call home.

If Joel in Risky Business is the epitome of privilege, Malcolm is his far more interesting reflection. That doesn’t make Dope a better film, it just makes it worth watching. (But, then, I love Risky Business.) While much of Dope is constructed of typical coming of age, teen comedy beats, enough of it also isn’t. Famuyiwa manages to make a film about black Americans that isn’t exclusively for, or exclusively appealing to, black Americans.

This is a rarer accomplishment than it should be.

Most movies, by default, get made for the majority (read=white) audience. Either that, or they nod to multiculturalism with a few ethnic characters and/or Denzel Washington — the Fast & Furious films being notable exceptions. Most films by black directors and staring black casts are made for and marketed to black audiences. (Case in point, this is the first film of Famuyiwa’s I’ve seen.) That’s not necessarily racism, but it is a result of ingrained racism. It’s Hollywood accepting what is instead of pushing for what should be. Same, too, audiences, including me.

Dope, however, is clearly about the black American experience. It’s just that it manages to be so for everyone’s benefit and appreciation. Not in a historical, reflective way like Selma; more like a much better, less strident Dear White People. In that fashion, it is informative, and remarkably so. Malcolm’s life is one that’s as based in reality as Tom Cruise’s character’s is in Risky Business. Malcolm embodies a reality that most Americans never consider. Underneath the shenanigans and sex scenes, Dope lays this out like a line of psychoactive truth.

So why is Diggy a lesbian? Why is Jib such a lightweight? Why does Malcolm want to go to Harvard?

Those are the wrong questions. The real question, Famuyiwa suggests, is why you expect them to be some other way. If films for decades have taught you to think of black teenagers in impoverished Los Angles solely as gangsters, thugs, or potential drive-by victims, that’s not necessarily racism, it’s just most likely racism.

When, in Risky Business, Joel turns his suburban Chicago house into a brothel, he’s making the best of a bad situation. The fact that it all turns out okay is a comment on the ironies inherent in our way of life. In Dope, when Malcolm sells drugs to make the best of a bad situation — is that, or isn’t that, precisely the same thing?

Go on. Ask the American justice system. I dare you.

Rick Famuyiwa has slipped us all a mickey with his film. It looks and tastes untainted, but the dose gets drunk. He spells it all out a bit bluntly in the end, having wandered a bit in the getting there, but the message is clear. It is also one he earns the right to deliver with Dope.

If Princeton needs men like Joel, then Harvard needs men like Malcolm, Hollywood needs men like Famuyiwa, and America needs to kick itself into shape, take a long look in the mirror, and demand an answer to the question: ‘what the fuck?’