Have you ever sat around an untidy living room, endlessly swapping movie quotes with your friends? (Me too.) Here’s the thing, though; imagine how that sort of scenario might play out if the only people you had to talk to were your immediate family members, and if your range of motion was limited to the interior of a run-down, four bedroom, Lower East Side apartment. That surreal reality is the subject of The Wolfpack, a documentary about the Angulo brothers, their confinement, and their escape. First they escape into a fantasy world of film and then they physically escape into the real world of New York City.

Have you ever sat around an untidy living room, endlessly swapping movie quotes with your friends? (Me too.) Here’s the thing, though; imagine how that sort of scenario might play out if the only people you had to talk to were your immediate family members, and if your range of motion was limited to the interior of a run-down, four bedroom, Lower East Side apartment. That surreal reality is the subject of The Wolfpack, a documentary about the Angulo brothers, their confinement, and their escape. First they escape into a fantasy world of film and then they physically escape into the real world of New York City.

Somehow documentary director Crystal Moselle gained access to this forbidden and forbidding kingdom — for it really exists, even now — and to these real-life characters. To some degree, in The Wolfpack, she shares her backstage pass with all of us.

The Angulo brothers — who have names, but who do not quite take shape as individuals in this documentary — grew up locked in their apartment by their father, Oscar. Their brainwashed mother, Susanne, for reasons uninvestigated, allowed Oscar to keep her in thrall to his listless impersonation of a cult leader. She let herself be cut off from the entire world — including her own mother — for decades.

As the film relates, the Angulo family only got out of this grim apartment a handful of times a year, and then only as unit. Daddy Oscar held the door’s only key. The boys compensated for their forced seclusion by re-enacting scenes from their favorite films.

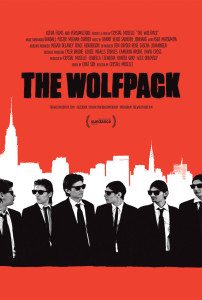

Their amateur productions (The Dark Knight, Reservoir Dogs, etc.) — seen performed for Moselle’s camera and via warped home video footage — are uncanny. The boys mimic each actor’s inflection, each movement, and do so in a manner that seems just shy of religious. Their costumes, constructed from cardboard boxes and yoga mats, shame every Halloween you’ve ever seen.

Their amateur productions (The Dark Knight, Reservoir Dogs, etc.) — seen performed for Moselle’s camera and via warped home video footage — are uncanny. The boys mimic each actor’s inflection, each movement, and do so in a manner that seems just shy of religious. Their costumes, constructed from cardboard boxes and yoga mats, shame every Halloween you’ve ever seen.

But who are they? What is happening here? What manner of creature is Oscar? These questions are barely asked and never answered.

In The Wolfpack, we open the wrong door in the wrong housing project and end up in a bizarro sideshow. These aren’t freaks, though; they’re smart, tender kids who can’t stay cooped up forever. The eldest Angulo brother, Mukunda, at age fifteen — five years before filming, if my math is correct — slipped out on his own. He wore his homemade Friday the 13th hockey mask and cruised the neighborhood, finally cracking Oscar’s wall of control.

And then?

Mukunda, not knowing any better — having been locked in a dingy apartment for the vast majority of his life — walked into a bank dressed as a supernatural serial killer. The cops took him away for psychiatric evaluation. He was assigned a therapist and returned home. Thus initiated to the world, Mukunda proceeded to stiff arm his strange father and lead his brothers out on further forays. Somewhere in there there’s a SWAT raid on the apartment, but like everything else, why or to what end isn’t unveiled.

Mukunda, not knowing any better — having been locked in a dingy apartment for the vast majority of his life — walked into a bank dressed as a supernatural serial killer. The cops took him away for psychiatric evaluation. He was assigned a therapist and returned home. Thus initiated to the world, Mukunda proceeded to stiff arm his strange father and lead his brothers out on further forays. Somewhere in there there’s a SWAT raid on the apartment, but like everything else, why or to what end isn’t unveiled.

In The Wolfpack, the story comes out through raw interviews. Moselle’s camera is frequently, literally unfocused, her subjects half lit and/or in motion. The boys talk of their father. They offer hand-me-down explanations for who he is and why. Their mother comes into frame, too. She offers little clarity or data, shrugging and rationalizing her way through a lifestyle not far off from Nell or The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. Only smack dab in the middle of Manhattan.

Oscar does not submit to interviews, but he is there. He drinks copiously and speaks a little and sprawls across the film. He’s the largest mystery around and he’s left totally unexamined. If Moselle ever asked him what he thought he was doing, she didn’t include the footage. If he ever told Moselle she wasn’t welcome in his fief, or tried to keep her from his sons, that too is utterly absent.

Oscar does not submit to interviews, but he is there. He drinks copiously and speaks a little and sprawls across the film. He’s the largest mystery around and he’s left totally unexamined. If Moselle ever asked him what he thought he was doing, she didn’t include the footage. If he ever told Moselle she wasn’t welcome in his fief, or tried to keep her from his sons, that too is utterly absent.

And so we’re left knowing something odd exists but knowing little of why. The Angulo boys (fine: Mukunda, Narayana, Govinda, Bhagavan, Krisna, Jagadesh, plus their either shy or ensorceled sister Visnu) make fascinating subjects for a documentary. They are engaging boys who have made the most of a raw deal. In The Wolfpack, we get to watch them take wing, leaving the nest too late and too soon. But this film is a monster movie that never gets around to showing the monster.

There, on the couch, drinking wine, is the Joker, or at least Mr. Blonde, and of him we know nothing. Jaws never leaps from the water to make a snack of Quint and show off his choppers; Nurse Ratched passes out her pills but she never emerges from the nurse’s station to slay McMurphy with an icy smile.

I’m glad the Angulo boys — and Susanne and Visnu — have brokered some escape from their physical and psychological prison. I’m glad they did so creatively and with a minimum of malice. The Wolfpack is fascinating for opening them to the world and the world to them, but it’s not much of a documentary.

I suspect the Angulo brothers would construct a better film left to their own devices, and hope they do.