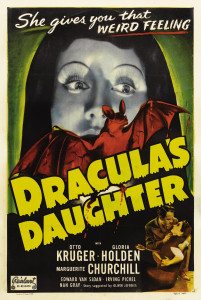

Dracula’s Daughter has a rep for being the first vampiric lesbian flick, but having emerged from the tomb in 1936, you’re going to have to dig awfully deep to find anything transgressive about it. Yes, it features an arguably manly woman dressed in hipster black cruising the streets of London in seach of victims, and a scene in which she makes a young woman take off some of her clothing in order to “pose” for a painting, but that’s it for suggestions of lesbianism. Contemporaneous reviews noted it or, in some cases, didn’t. Universal was worried enough about any such implications that they toned down the script again and again to ensure nothing untoward made it to the screen, and not much did. (Though the tagline on the poster is “She gives you that weird feeling.” Hm.)

Dracula’s Daughter has a rep for being the first vampiric lesbian flick, but having emerged from the tomb in 1936, you’re going to have to dig awfully deep to find anything transgressive about it. Yes, it features an arguably manly woman dressed in hipster black cruising the streets of London in seach of victims, and a scene in which she makes a young woman take off some of her clothing in order to “pose” for a painting, but that’s it for suggestions of lesbianism. Contemporaneous reviews noted it or, in some cases, didn’t. Universal was worried enough about any such implications that they toned down the script again and again to ensure nothing untoward made it to the screen, and not much did. (Though the tagline on the poster is “She gives you that weird feeling.” Hm.)

I’d say not much of anything made it to the screen. At 70 minutes, Dracula’s Daughter is one of the longest movies I’ve ever sat through. I’ve watched Tarkovsky films that felt shorter. Old horror movie sometimes have their charms, but more often than not, whatever might have felt shocking in the ‘30s is long past startling anyone today. The ones that still work—the original Dracula, for example—work because they’re made well. Dracula’s Daughter is not made well.

One can imagine way back then any suggestion of, as in this case, a woman possessed by evil searching out victims to suck dry being enough to scare the pants off of people. Where else to encounter such a story? Some books here and there? Maybe? Going to the movies and seeing these kinds of stories on screen must have been a thrill, no matter the minimal horrors on display. Merely the idea of such happenings would be enough to unnerve anyone.

Today you can’t get out of bed in the morning without tripping over a zombie. The mere idea of the undead arriving in all their many forms to feast on the living is about as scary as curdled milk. (Less scary, even. Have you ever found you’ve poured bad milk on your cereal flakes? You’ll have nightmares for weeks.) So when all an old horror flick has going for it is a woman out for blood, you’re in grave trouble.

The story barely exists. It picks up immediately where Dracula ends, with Von Helsing having just staked Dracula. He’s arrested by Scotland Yard, but wait, he says—Dracula’s been dead for 500 years; I can’t have killed him!

They arrest him anyway. Meanwhile, Dracula’s daughter, Countess Zaleska, arrives with her hulking man-servant, Sandor, steals Dracula’s body, burns it up in the hopes his curse on her will be lifted, fails to find herself uncursed, so asks a psychiatrist, Dr. Garth, on hand to defend Von Helsing, to rid her of her urges. It doesn’t work. In the end, she gets an arrow through the heart.

The script is wretched from start to finish. Reading about the production, it might as well have been made today. Draft after draft, writer after writer, rights to Bram Stoker’s works bought and sold and passed between studios and producers, hot directors courted, etc. and so on, all in order to crank out a money-maker like its beloved predecessor. Which money it failed to make. As it turned out, Dracula’s Daughter was the last of Universal’s famed run of horror movies of the era. Three years went by before they returned with Son of Frankenstein, a big hit.

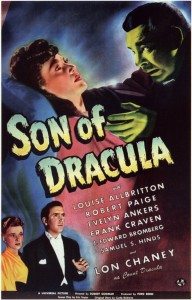

“Son of Frankenstein? Why not Son of Dracula?”—said surely everyone working for Universal. And so Son of Dracula was born in 1943. It’s quite a bit better than Dracula’s Daughter, thanks in part to its director, Robert Siodmak, a German director just beginning his Hollywood career, who’d become best known for his film noir work (The Suspect, The Killers, Criss Cross, etc.). It looks nice, and includes a number of the sort of shadowy shots soon to blossom in film noir.

“Son of Frankenstein? Why not Son of Dracula?”—said surely everyone working for Universal. And so Son of Dracula was born in 1943. It’s quite a bit better than Dracula’s Daughter, thanks in part to its director, Robert Siodmak, a German director just beginning his Hollywood career, who’d become best known for his film noir work (The Suspect, The Killers, Criss Cross, etc.). It looks nice, and includes a number of the sort of shadowy shots soon to blossom in film noir.

Also new—wild special effects! Including a bat flapping around, landing on prone victims, and biting their necks. Well, the biting is implied. Can’t go around showing that kind of thing, now can we? The vampire in question, known as Count Alucard (get it?), is also seen both turning into and disappearing from a cloud of fog. Fancy!

The story is absurdly convoluted. A seemingly nice lady, Katherine, is in love with Frank, yet she’s invited this mysterious Count Alucard to stay at their mansion. She then absconds with Alucard and marries him, is mistakenly shot dead by Frank in a failed attempt to kill Alucard (the bullets go right through him!), is then brought back to vampiric life by Alucard, and then, stay with me here, goes to Frank, explains she’s still in love with him, and only married Alucard in order to gain eternal life which she can now pass on to Frank by turning him into a vampire!

Sure, it sounds like a foolproof plan, but for whatever unexplained reason, Frank doesn’t want to live the eternal life of the undead, and torches her coffin with her in it.

Alucard is played by Lon Chaney, Jr., famous for starring in Universal’s The Wolf Man in ’41 (and The Ghost of Frankenstein and The Mummy’s Tomb in ’42). For an actor who’s been in as many movies as he has, it’s impressive to see what a godawful performance he gives in Son of Dracula. He’s like a piece of plywood, but less expressive, and not nearly as terrifying.

And still it’s a better movie than Dracula’s Daughter. Though on reflection, not by much. I mean yes, there’s the bat flapping around, eerie mist, burning coffins, a crazy old witch, and the inklings of a film noir look, but in the end it’s still a boring slog.

I’d expected a little more pizazz from these movies, old-timey as they are. Alas. They’re a far cry from the best horror the era has to offer. Which are what, you ask? For starters, try Dracula. And Dreyer’s Vampyr. And Lewton’s Cat People. And Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. And of course the never boring Island of Lost Souls.