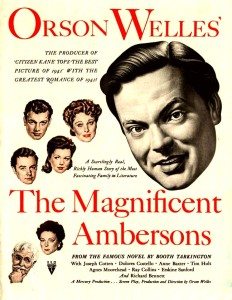

There is always, continually, that one film that you’ve always meant to see but somehow never got around to. Up until last night, for me, that film was Orson Welles‘ tragically disemboweled 1942 semi-masterpiece The Magnificent Ambersons. Now it will have to be something else. Maybe Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler?

There is always, continually, that one film that you’ve always meant to see but somehow never got around to. Up until last night, for me, that film was Orson Welles‘ tragically disemboweled 1942 semi-masterpiece The Magnificent Ambersons. Now it will have to be something else. Maybe Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler?

In any case: The Magnificent Ambersons. Seen it. And, despite its tragic disemboweling by studio hacks at RKO, I liked it quite a bit.

Welles’ take on the Booth Tarkington novel tracks the decline of one wealthy family as the automobile reshapes the landscape of America. It’s a film that manages to be grand and sweeping while never leaving home. Welles regulars Joseph Cotten and Agnes Moorehead join a cast including Anne Baxter (All About Eve) and Tim Holt (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre). The film centers on Holt’s George Minafer, a spoiled louse and heir to the Amberson fortune, whose entitlement slowly but surely spells his ruin.

Good stuff, that. Welles’ film is about comeuppance and — in a strange, nearly satisfying way — how seeing it dished out is not quite as delicious as one might dream. I say only ‘nearly satisfying’ because Welles’ original edit was snaked away by RKO while he was overseas and eviscerated. More than 40 minutes of his film was either cut or re-shot, mostly softening the ending and, in many cases, making the new ending dopey and inexplicable.

It is one of the great tragedies of cinema. One might fantasize, like with The Passion of Joan of Arc, somewhere in some forgotten niche hides Welles’ original edit — prints of which existed, for preview screenings, and another of which was sent to Welles in Brazil. So far, however, no luck — but forgotten niches remain unsearched. Please check yours now.

Writing about The Magnificent Ambersons, having only just seen it for the first time, feels a bit like describing the Grand Canyon or a particularly nice sunset. What can I say that hasn’t already been said, at far greater length, by scholars who are not currently covered in baby drool? All that is left for me to add is my personal reactions, which are by and large wistful.

Tim Holt as George is now one of my favorite villains of cinema. Like Popeye Doyle, he is his own problem. There is little tragedy in The Magnificent Ambersons that couldn’t have been avoided with just a smidgen of humanity and empathy osmosing out of Georgie boy — even if both were only faked, and faked poorly. Our hero cannot even manage that. He is, without a doubt, a louse and the worst kind of louse at that: the kind that thinks he’s the acme of civilized gentility.

You want to punch him in the neck repeatedly. It’s a lovely performance.

In George’s wake fall characters less central, but due to the construction of the allegory, also paradoxically more central. As the audience, we are not George — never George — but instead those who enable him, or cater to him, or endure him. You will note there are no characters in The Magnificent Ambersons who are able to rein in George effectively. As Anne Baxter’s Lucy suggests, late in the film, to her father, in a scene that feels orphaned, sometimes there are ‘braves’ who are cruel and uncontrollable, but who also cannot ever be replaced.

This lament is the heart of The Magnificent Ambersons but that does not make its telling resonate. In the version of the film that’s available, Lucy’s affection for George is curious and only acceptable allegorically. Lucy’s father — Joseph Cotten’s Eugene — is kept from his true love, George’s mother (Dolores Costello) by George’s domineering egoism. So this scene, in which Lucy lamely attempts to justify George’s compelling power to the person he has most harmed? Well, it’s damned weird. It springs from nowhere, lost in time as George drags his mother around the world to keep her from Eugene, while who knows what happens to the Ambersons.

Except, at least in Welles’ edit, one would know that this stretch of time marks when the Ambersons unwisely invested in a headlight company, to lose the fortune upon which George depends. But since those scenes were cut in the RKO release, you’ll just have to figure out for yourself why all of sudden George is penniless, orphaned, and faced with a nice steaming bowl of comeuppance.

A line of dialogue here and there tries to retrofit new scenes into an old story, but it’s lame at best and mostly little better than frustrating.

Some of Welles technically brilliant direction remains, drawing you through scenes of length with focus that reveals and suggests and impends. Other scenes, such as a long take that drew you through three floors of Amberson mansion to join a ball, do not. Because history hates you and doesn’t want you to have nice things. Like Bernard Herrmann’s score, also butchered in the process.

Have you checked all of your forgotten niches yet?

Made directly following Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons may well have usurped that film’s status as ‘best ever’ if only studio executives had thought audiences possessed some appetite for stories that ended without an upswell of positive emotion. Stories like The Third Man or Double Indemnity or I don’t know — maybe I should just forget it (it’s Chinatown)?

More’s the pity because the content of The Magnificent Ambersons, much like that of Citizen Kane, counsels us against that which plagues us still: losing one’s humanity in ravenous pursuit of social acclaim.

If you agree, please like this post on Facebook.