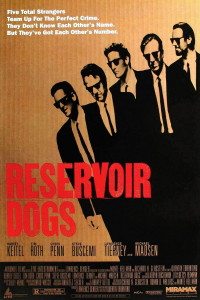

Reservoir Dogs is a punch in the gut. It’s a fierce, violent, profane, and very funny heist movie without a heist, at once a throwback to ‘40s and ‘50s film noir and a herald of things to come. It premiered at Sundance in ’92 and was instantly bought by upstart Miramax, which with Tarantino’s next film, Pulp Fiction, would join the big time. As many people hated Reservoir Dogs as loved it. It was renowned for walk-outs at every screening. The intensity of the violence didn’t sit well with people used to ‘80s Hollywood cinema. Reservoir Dogs was something new. Something dangerous.

Reservoir Dogs is a punch in the gut. It’s a fierce, violent, profane, and very funny heist movie without a heist, at once a throwback to ‘40s and ‘50s film noir and a herald of things to come. It premiered at Sundance in ’92 and was instantly bought by upstart Miramax, which with Tarantino’s next film, Pulp Fiction, would join the big time. As many people hated Reservoir Dogs as loved it. It was renowned for walk-outs at every screening. The intensity of the violence didn’t sit well with people used to ‘80s Hollywood cinema. Reservoir Dogs was something new. Something dangerous.

Inedependent cinema existed before Reservoir Dogs—indeed, it’s always existed—but there wasn’t much of it in the ‘80s outside of Jarmusch, Spike Lee, and the Coens, the latter two of whose movies, at least following their debuts, were given relatively wide distribution. What Tarantino essentially invented with Reservoir Dogs was “indie movies,” which flourished for only a few years before being turned into a genre and subsumed by specialty arms of the majors.

Prior to Reservoir Dogs, independent movies were supposed to be thoughtful, character-driven, talky, influenced by stately European films of the ‘60s, movies you could imagine John Cassavetes having directed. They weren’t supposed to punch you in the gut, they weren’t supposed to be influenced by grindhouse movies of the ‘70s and Asian action flicks of the ‘80s. (As for the noir influence, the Coens beat Tarantino to that punch with their brilliant noir debut, Blood Simple, in ‘84.) Tarantino loves movies and with Reservoir Dogs he wanted us to know it. Like everything he’s made since, his characters weren’t meant to reflect the real world, they were meant to reflect other movies. Movies with a shitload of blood and bullets.

I saw Reservoir Dogs when it opened and many, many times thereafter. It’s always been my favorite Tarantino movie. But until last night I hadn’t seen it for at least a decade, probably longer. What surprised me most watching it again is its intensity. Twenty-three years later and still it punched me in the gut! I’ve got to hand it to Tarantino, the movie is truly audacious. Not a word I use often. He’s far from the accomplished stylist he’s since become (alas, to the detriment of the films overall (to my eyes, anyway)), but his enthusiasm is palpable. In every scene you feel him saying, “Let’s just fucking do this!”, and so they do. I mean, the balls on this movie. You can’t help but stare, half laughing, half aghast, at what he pulls off.

It’s a lesson in how to make a movie on a budget: Set eighty percent of it in an empty warehouse. Budget constraints are why Tarantino originally planned not to show the jewel heist, but even after Harvey Keitel got involved and the movie, though small, had real money behind it ($1.5 million), he decided to keep it out. The heist becomes the hole in the doughnut. Two flashbacks post-robbery—Mr. Pink’s (Steve Buscemi) escape and Mr. White (Keitel) and Mr. Orange (Tim Roth) stealing a car, Orange shot in the stomach—are all we see of what went down, with the most important puzzle piece—Mr. Blonde’s (Michael Madsen) “bullet festival”—left only in the telling.

The movie is all structural oddities. It begins with a bunch of guys at a diner talking Madonna songs and the etiquette of tipping, cuts to a slow-motion cool-guys-walking shot, then credits, then bam! We’re in the car with a bleeding, gutshot Mr. Orange in the back and Mr. White in front, trying to calm him down.

After that, most of the movie is a chronological story told in the warehouse, with a handful of flashbacks to various characters signing up for the job. In one scene, Joe (noir veteren Lawrence Tierney) assigns the crooks their fake names, but there’s not a word about how the heist is to be pulled off. So it’s a heist movie with no discussion of the heist, and no heist. Which is to say, the very elements that make heist movies heist movies. Tarantino says one major influence on the movie was Kubrick’s The Killing, which it resembles not in the least. The Killing is a classic noir heist movie: The planning of it is laid out in detail, and the heist itself is the centerpiece.

So, again—audacious. Somehow Tarantino knew his movie wasn’t about the details of a crime. It was about a bunch of crooks talking and shooting each other after a crime goes awry.

The most self-consciously stylized section of the movie is Mr. Orange’s flashback to his memorization and eventual delivery of the commode story. The story is told as a progression of scenes: Orange AKA Freddie practices it alone, practices it far more smoothly in front of his fellow cop, delivers it in character to Mr. White, Joe, and Nice Guy Eddie (Chris Penn), and, finally, speaks it aloud while the story plays out in front of us—Mr. Orange, marijuana in hand, finding four state troopers and their German shepherd in a bathroom. It’s the kind of sequence that led people to compare Tarantino to Scorsese. He’d of course go on to play with structure and time even more dramatically in Pulp Fiction.

Everyone’s a bad guy in Reservoir Dogs, aside from Freddie/Mr. Orange, yet one doesn’t feel especially sympathetic toward the undercover cop, because in Tarantino’s world, the crooks are the guys you want to hang out with, they’re the cool guys, they’re who he wants to be, and therefore so do we. Freddie seems like a bit of a dope. When he’s picked up by the crooks before the robbery, we cut briefly to the unside of an unmarked police car tailing them and hear one cop say to the other, “A guy has to have rocks in his head the size of Gibralter to work undercover.”

Freddie’s so careless he’s shot, not by a crook or a cop, but by the lady in the car he and Mr. White steal. He shoots her in response. Oops.

Everyone dies in the end, and they all had it coming. (Save Mr. Pink, who runs off with the diamonds only to be nabbed instantly. “Don’t shoot!” we hear him yell.) Everyone is betrayed, everyone is a hothead, nobody trusts anyone. In every classic noir scenario, the “hero” is screwed from the start. Tarantino wastes no time in Reservoir Dogs, with Mr. Orange bleeding out from the get-go. From Orange’s perspective, the whole movie is his death scene. “I’m gonna die!” he cries at the outset, and in the end, admitting his betrayal, Mr. White kills him. His infiltration of Joe’s circle winds up succeeding in one sense—Joe and his boys won’t be robbing anyone again—but at quite a cost: his own life, and that of a lot of cops.

Tarantino’s subsequent movies are more concerned with style and banter and nods to past movies than they are with story. Reservoir Dogs is stylish in its rawness, its intensity, and its focus. There are no extraneous conversations, no extraneous characters, nothing that doesn’t drive it forward, hard. The only really “Tarantinoesque” conversation is the one that opens the movie, and it’s there for a reason, to introduce the characters as regular guys, who for all we know are regular guys. It’s to contrast the carnage to come.

His new movie, opening at the end of 2015, The Hateful Eight, appears to be another voilent story with a small cast of characters. I’m guessing it won’t have the impact of Reservoir Dogs. But who knows? Maybe it’s the Tarantino gut-punch we’ve been waiting for.