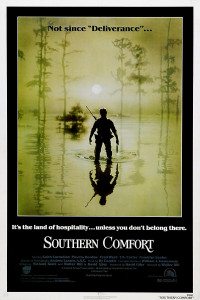

In Supreme Being’s recent run through of 48 Hours and the work of director Walter Hill, mention was made of Southern Comfort. This, beyond being the name of a sickly sweet adult beverage that escorted many a talented 60s-era musician to his or her grave, is also the moniker of a 1981 action film, directed by Hill. As the comments to SB’s post suggest, Southern Comfort is a film of debatable merit.

In Supreme Being’s recent run through of 48 Hours and the work of director Walter Hill, mention was made of Southern Comfort. This, beyond being the name of a sickly sweet adult beverage that escorted many a talented 60s-era musician to his or her grave, is also the moniker of a 1981 action film, directed by Hill. As the comments to SB’s post suggest, Southern Comfort is a film of debatable merit.

Is it just a muddy, violent, stupid excuse to pit a few redneck national guardsmen against ghostly Cajuns in the deep bayou, Deliverance style? Or, perhaps, it is a film that’s intentionally muddy; violent in a fashion that is purposefully unjustifiable; and no more stupid than any foreign martial action in the South East Asian jungle.

After concentrated study, I am here to clarify exactly how long a shrift Southern Comfort deserves.

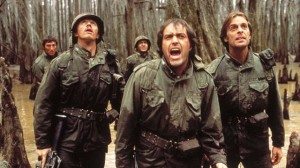

To begin, surely you must first read about Walter Hill and his odd, Peckinpah-esque oeuvre of wanton violence and lowly goals. In Southern Comfort, this pattern holds steady. Powers Boothe plays Hardin, a Texan transplant to a Louisiana national guard unit that includes an all-star cast of unassuming ass-kicking actors: Peter Coyote, Keith Carradine, Fred Ward (Tremors), T.K. Carter (The Thing), and Lewis Smith (Buckaroo Banzai). Together, these yokels set out on a patrol across the swamps. What they’re patrolling for, except practice, is to prove how rough and ready they are.

Then everything gets royally fucked, because rough and ready they are clearly not. Their roughness is pretense, especially as compared to that of those they antagonize.

To the strains of an incongruously excellent Ry Cooder score, these half soldiers avail themselves of every opportunity to dig themselves into as deep a hole as possible. Getting lost, they liberate canoes off some backwoods boys, in jest fire a fusillade of blanks at the Cajuns from a machine gun, and then — to their shock — find their Sergeant’s skull amended with an extra dose of lead.

This is what happens when you turn survival into a game: you lose.

Hunted, lost, and increasingly unmanned, the squad spirals down into the murk. Their assumed superiority gets pummeled by their own uncontrolled aggression. Their assumed intelligence gets ravaged by a complete lack of leadership. They play solider and the Cajuns — including a mostly silent Brion James — whittle them to bits.

Southern Comfort isn’t a nice film. It looks as grey and miserable as it must have been to shoot. Over its length, nary a character you might admire appears. Even Hardin, the protagonist, is just a cynical, sour prick. It is tense, and rough, and rarely beautiful, save for the work of Ry Cooder and, later, in the contrasting camaraderie of the Cajun village that some surviving guardsmen stumble into.

While the obvious comparison is to Deliverance, this is only tangentially that kind of film. More so, it is like the work of Ted Kotcheff, such as First Blood. It is a film about bringing the war home, both figuratively and literally. To watch Southern Comfort and not think of Viet Nam is impossible, and pointless.

As Hill said:

…we were very aware that people were going to see it as a metaphor for Vietnam. The day we had the cast read, before we went into the swamps, I told everybody, “People are going to say this is about Vietnam. They can say whatever they want, but I don’t want to hear another word about it.”

But since I’m fairly sure Walter Hill doesn’t read this blog (if he does: ‘hi’), let’s talk Viet Nam and Southern Comfort. Stupid and unaware: most definitely this describes the film’s characters, without disguise or subterfuge of any kind. Hardin asks Carradine’s character point blank what is happening when it could not be more obvious. Yes, all of these guardsmen, including Hardin, are culpable. They wander into a foreign land, unaware of the local customs, disinterested in courtesy. Finding themselves wrong-footed, they again and again dig in, escalating instead of accepting their inferiority.

Even those in the party who might question the wisdom of their actions have no control over those who don’t — and those who don’t are by and large insane. The squad is trimmed, in a permanent fashion, through murder, fracture, and suicidal action. Their Cajun adversaries display inhuman ability to track and trap them. As natives, their intelligence is both unrecognizable and superior.

As the situation explodes, the viewer must ask: what are these army interlopers trying to accomplish? For Powers Boothe’s Hardin, the goal is survival. Others get tangled in revenge, or duty, or the demands of ego. Making the leap to Viet Nam from here isn’t challenging.

And when our final few men struggle through, and end up in that Cajun village, the shock is how uncivilized they are — ‘they’ being the guardsmen, not the Cajuns, who dance and feast and extend hospitality.

War is something you bring with you. In Southern Comfort, violence is a response to violence. Men who open those doors, they’re more than foolish; they’re stupid. The mud and swamp that envelops them, it’s as symbolic as it is deadly. So yes. Southern Comfort is a violent, muddy, stupid film for violent, muddy, stupid men. And being so, it isn’t half bad.

Awesome… It’s on my list for sometime this week.

Know what would be an interesting exercise for a film student? (You guys were thinking of getting an intern, right?) An exploration of politics and social mores by contrasting the work of reasonably serious directors with the contemporary studio-produced trailers for their films.

The first 30 seconds of the Southern Comfort trailer are GOLD!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7V6gITreRA

I nominate you to be intern, Jason.

How bout official blog cocktail-taster? I could probably squeeze that in.

If you’re pouring: okay.

Having read this piece and watched this trailer, there is, I am happy to report, no chance I’ll be rewatching Southern Comfort anytime soon.

Just the Long Riders for you, then?