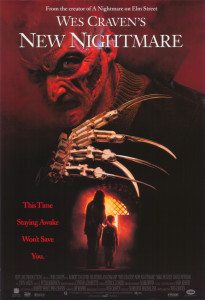

Ten years after making A Nightmare On Elm Street, creator Wes Craven returned to the series with a kind of meta-sequel titled, rather laboriously, Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (’94), that tells the story of actress Heather Langenkamp, star of the first film, being terrorized but what seems to be a real life Freddy Krueger. It wound up being the least successful film in the series, but the best reviewed of the sequels. Which suggests it’s a movie too smart for its own good. Or worse, not smart enough.

Ten years after making A Nightmare On Elm Street, creator Wes Craven returned to the series with a kind of meta-sequel titled, rather laboriously, Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (’94), that tells the story of actress Heather Langenkamp, star of the first film, being terrorized but what seems to be a real life Freddy Krueger. It wound up being the least successful film in the series, but the best reviewed of the sequels. Which suggests it’s a movie too smart for its own good. Or worse, not smart enough.

Without credits, the movie opens with a shot of Freddy’s metal claws being built by someone off-screen. The claws wriggle on their own when finished and caress the hand of their builder—which hand the builder hacks off with a cleaver. Blood splatters the crew filming the scene. Wes Craven appears in the background, directing. Heather Langenkamp is there with her husband, Chase (David Newsom), and a couple of special effects guys. They toy with the claw—and it comes to life and attacks.

But surprise! It’s all a terrible dream. Heather wakes up in the midst of an earthquake with her hubby. Later, she notes his hand is cut in the same spot where the claw cut him in her dream. So, yeah. Not really a surprise.

Heather has of late been tormented not only by dreams of Freddy but by phone calls from him. Or, you know, some crazy fan pretending to be him.

And there’s your movie. Freddy’s on his way into the real world, and Heather has to protect herself and her young son, Dylan (the seriously fucking creepy Miko Hughes, who played the seriously fucking creepy kid in Pet Sematary), and her husb—oops, no, poor Chase gets offed pretty quick, which troubles Heather for like five minutes of screentime. But it’s cool. He was pretty lame.

What’s going on, it turns out, is that, unbeknownst to Heather, Wes Craven has been writing a new Nightmare script, and wants her to star in it. You see, it’s a movie about Freddy breaking into the real world, and yes, of course it’s the very movie we’re watching. What Craven is writing is playing out for real. How’s he going to end the story?

Heather meets with Craven and he explains what he’s writing. He explains it at length, in a way one generally would want to avoid in a horror movie. What he explains is the very reason horror exists in a way a smart man who’s been working in horror all his life would explain it. Freddy isn’t really Freddy, he’s an evil entity, he’s the evil entity, the one who in its infinite forms inhabits all stories. And the thing is, says Craven, when a certain form becomes too well known, too over-exposed, too comedic (for all you dunderheads out there, he’s talking about all the other Nightmare sequels, and Freddy’s fame), when the form becomes tired and stale, the evil thing will try to break into the real world. The only way to stop him is to trap him in another genuinely scary story. Like this one Craven is writing, and we are watching.

Which is all well and good and true. But by explaining what he’s doing, he winds up robbing the movie of anything genuinely frightening. Freddy becomes less a character and more a representation of the fear of death—and yes, of course that’s exactly what he is, horror stories exist to allow us to safely live out our fear of death—but stating it outright turns Freddy from a terrifying monster into an intellectual exercise.

More problematic still is that nothing surprising or transgressive unfolds in the telling of this tale. What Craven says comes exactly true. Freddy is trying to bust his way into reality, and Heather is to him the gatekeeper he must kill to succeed. The only way to defeat him is to make the movie we’re watching and to have Heather beat him at the end. Guess what? She beats him at the end.

I don’t understand why Craven didn’t have Freddy outsmart everyone, at least for part of the time, at least enough to keep us off-balance. Why doesn’t Freddy kill Craven? Or New Line exec Bob Shaye, who also appears as himself? Or Robert Englund, for that matter? If Englund is being presented as himself and not the Freddy causing the trouble, why not have Freddy kill him in some wild way? (Even in the credits, Freddy is listed as “himself.”)

In all of these scenarios, what’s real and what’s a dream would be in play, whereas the actual movie has none of that. We’re never unsure of where we are. The only dreamer is Heather’s son Dylan. His traumas just aren’t very compelling.

Craven knows how to make every scene, even every beat in every scene, build and release tension as we wait for something horrible to happen, but he doesn’t vary his attack. The creeping tension rises and falls like a lulling heartbeat. In the end there’s the final battle between Heather and Freddy, but nothing about it is scary. It’s fine we know she’s going to live, but no one else is around to be hacked up, at least no one we care about.

Craven’s intention with New Nightmare was to make Freddy scary again. He succeeds in giving us a Freddy who isn’t a comic figure with funny lines we cheer on to further acts of creative violence, but fails in the larger goal of turning him into a figure of dread. It’s as though by saying he’s now “real,” he’s less threatening than when he lived only in nightmares.

Craven also made the decision to change Freddy’s makeup into what to me looks especially fake and masklike. He’s meant to be taken more seriously, but he looks more like a cartoon than ever. Aside from that, the movie looks good, and some truly creepy moments crop up, like a scene early on where Heather is surprised on a talk show by Englund dressed as Freddy bursting onto the set, high-fiving kids in the audience wearing Freddy masks, and glowing ominously in the stage lights. But overall, Craven is hampered by his too intellectual, too sedate take on the story.

I was reminded of last year’s far superior The Babadook, another movie about a single mom whose child is obsessed by visions of a monster. Aside from being terrifying, The Babadook is clearly a metaphor for motherhood, or at least one angle of it. New Nightmare has a similar focus on Heather and her young son (and an almost identical scene on a playground), but has nothing to do with the horrors of motherhood. It’s about the horrors of horror movies. It’s about Craven reflecting on what creating a famous monster does to its creators.

It’s an interesting premise. It’s not dumb. It’s a genuinely thoughtful movie. It’s just not scary.