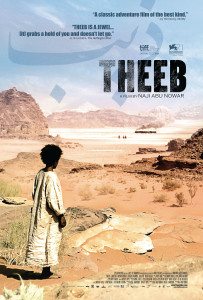

The Arabian Peninsula in 1916 is hardly the setting for Little Red Riding Hood, and that’s fine, as the film Theeb (Wolf) is a carnivore of an altogether different disguise. It is an adventure tale in Arabic and of Bedouin sensibilities.

The Arabian Peninsula in 1916 is hardly the setting for Little Red Riding Hood, and that’s fine, as the film Theeb (Wolf) is a carnivore of an altogether different disguise. It is an adventure tale in Arabic and of Bedouin sensibilities.

These are sensibilities that might not immediately come clear to non Bedu viewers. There are subtitles to Theeb, but that’s no guarantee of easy translation. Watching this quiet, deliberate, low-key adventure story presents you with a slow-burning mystery of ‘how’ and ‘why’ and ‘what now’.

These same questions motivate the film’s protagonist, a young boy saddled with the ambitious name of Theeb, which means ‘wolf’. As opening titles introduce and later dialogue illuminates, the wolf — to Beduins — is no simple slavering killer. The wolf is crafty enough to survive the merciless desert. He can navigate the society of his pack or dare to strike forth alone. The wolf lives where others surely die.

And here, the wolf is Theeb, a boy of about ten years.

Unlike you might expect of a Hollywood boy’s-own adventure, Theeb exaggerates nothing. The story and its inhabitants are people of realistic ability. They do as they’ve been raised and as their environment demands. In the beginning, this means learning to hunt, to care for livestock, and to keep your ears open.

Theeb’s older brother Hussein alerts his clan to strangers approaching. As Beduins must, they offer the travelers hospitality. The strangers — a British officer and his guide — request an escort along a disused, now dangerous trail to Mecca made obsolete by the railway. Hussein honors his recently deceased father, the Sheikh, by acquiescing. Theeb follows behind uninvited.

He follows through a desert washed of color and contrast. He joins the party, one vague of intent but still ominous. Violence comes and the decision must be made: do Hussein and Theeb let their guests continue alone or do they extend their protection farther into the endless unknown?

He follows through a desert washed of color and contrast. He joins the party, one vague of intent but still ominous. Violence comes and the decision must be made: do Hussein and Theeb let their guests continue alone or do they extend their protection farther into the endless unknown?

As Theeb pushes deeper into a world without definition, one feels increasingly lost. What is happening is quite clear. Why it occurs; this is indicated for those willing and able to follow the fading trails. As calamity spirals, Theeb must increasingly navigate for himself. It is in this expression that the film reveals the most value.

If the boy were in a J.J. Abrams film, he’d stage his own armed rebellion and that would mark him a hero. Doing so — at ten — would, however, be ridiculous. Theeb’s actions and reactions are on a scale much smaller and more human. Because this is so, Theeb is more interesting and oblique.

This is director Naji Abu Nowar’s feature film debut and it is a quietly impressive one. He has cast well, enlisting young novice Jacir Eid in the title role. Cinematographer Wolfgang Thaler opts to skip the high drama of Lawrence of Arabia‘s scalding sun in favor of haze and monochrome envelopment. His compositions, when they reach their apex, feel exactly right emotionally.

This is the desert that needs no exaggeration. It is the simple, slow threat of death. It is the gentle encroachment of understanding and adulthood.

Theeb finds its way to its end, as its wolf-boy finds his way to a new understanding of the laws of his life. What is hospitality, what is threat, and where —in between — stands a man?