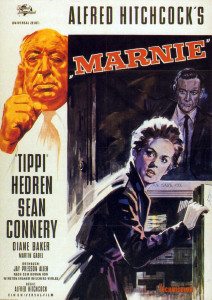

I wonder if anyone in ’64, when Marnie opened, knew it was the beginning of the end for Hitchcock? The Birds, itself not exactly the master at the top of his game, came out the year before, and it’s his last (arguably) watchable film. For whatever reason, Marnie is still looked on with fondness by some, I can’t imagine why. It’s a movie that exists for one reason only: to allow Hitchcock to film a rape scene. Or so one must surmise, so gleefully is it presented. Not only that, but the film’s original writer (Evan Hunter, writer of The Birds), begged Hitchcock not to go with rape, and wrote an alternate scene. Hitchcock fired him and hired Jay Presson Allen, who told Evan he’d made the mistake of bitching about Hitchcock’s reason for making the movie.

I wonder if anyone in ’64, when Marnie opened, knew it was the beginning of the end for Hitchcock? The Birds, itself not exactly the master at the top of his game, came out the year before, and it’s his last (arguably) watchable film. For whatever reason, Marnie is still looked on with fondness by some, I can’t imagine why. It’s a movie that exists for one reason only: to allow Hitchcock to film a rape scene. Or so one must surmise, so gleefully is it presented. Not only that, but the film’s original writer (Evan Hunter, writer of The Birds), begged Hitchcock not to go with rape, and wrote an alternate scene. Hitchcock fired him and hired Jay Presson Allen, who told Evan he’d made the mistake of bitching about Hitchcock’s reason for making the movie.

To be fair, Marnie (Tippi Hedron) needed to be raped, so she could experience, for the first time, the touch of a man. What an introduction! She’s lucky Mark Rutland (Sean Connery) took an interest in her. And not just any interest. A scientific interest. You see, Rutland is known for his ability to tame wild jungle cats. On his office desk is a photo of a jaguarundi he tamed in Africa. The close-up of the photo is priceless. Had me laughing for the rest of the movie, and lord knows the movie could have used some laughs. Marnie is presented as another wild animal in need of a firm but gentle, um, hand to tame her, and boy does she ever get it.

We meet Marnie just after she’s stolen ten grand from her office job. Rutland, a client, chats with the manager, and is mildly interested in this lowly secretery who made off with the cash. Bad luck for Marnie that the next office she hits is Rutland’s. He’s on to her in an instant. The moment she makes off with his cash, he’s there to grab her. Grab her, abduct her, blackmail her into marrying him, rape her to show her who’s boss, and, once she’s tried and failed to drown herself, forces her, at long last, to face the childhood trauma that turned her into a frigid, man-hating thief. After which they live happily ever after, one is asked to presume.

Marnie herself is shot by Hitchcock as if she were literally a jungle cat liable to scratch any who dare pet her. She backs into corners and huddles up on sofas while calm, cool Rutland inches ever close, assuring her he means her no harm. What’s a little rape between newlyweds on their honeymoon cruise?

Hitchcock’s treatment of women in his movies has long been a matter of debate. Is he a feminist or a misogynist? On the one hand, many of his female characters possess uncommon (for the era) depth and agency, while on the other hand, they’re often crooks, shrews, harpies, dishrags, or mummified and stored in the basement. Let’s agree Hitchcock’s relationship to women is complicated.

Marnie’s no pushover, I’ll give her that. She’s mean as hell. She’s also damaged. Terribly, terribly damanged. And for two long hours, Rutland, a confident manly man, teaches her how to behave. Seen in this day and age, it’s all a bit jaw-dropping. It was panned upon release, but seems to have gained cultural cachet since.

Is the love for this movie based on Marnie being so damned mean and disagreeable? Female leads are rarely if ever this unpleasant. She’s mean because she’s damaged, and she’s damaged because of a childhood incident I’d hate to spoil for you, but it won’t surprise you to learn that her old, spinster mother was once a whore. It was raining that night long ago, with thunder and lightning, and then…it happened. So much blood…so much blood! As an adult, Marnie still panics any time she sees red or a flash of lightning. Taking to thievery is merely the logical psychological result of her youthful trauma, and Rutland, by caging this wild beast and forcing her to confront her past, offers the perfect psychological solution.

Yes, psychology was simpler in those days, at least in the movies. Today we might wonder if Rutland’s cure—kidnapping, blackmail, rape, etc.—won’t have notably negative psychological effects themselves. Alas, we don’t have a Marnie 2: Jaguarundi’s Revenge to explore such matters.

Hitchcock’s oeuvre beyond The Birds sees little love, aside from the occasional attempt to claim for a movie like Marnie the mantle of “ignored masterpiece.” Maybe having been deified by Truffaut in the early ‘60s went to Hitchcock’s head. Maybe having his technique so deftly analyzed left him believing he had to explore different styles of filmmaking. After Marnie he made Torn Curtain (’66), Topaz (’69), Frenzy (’72), and Family Plot (’76). Of these I’ve seen only Frenzy, a mediocre Peeping Tom wannabe with another rather too gleeful rape scene, this one ending with death by strangulation. Hitchcock was once on the cutting edge of film, but no longer. Peeping Tom came out in ’60.

Or is the draw of Marnie Hitchcock’s style itself, still on display in how he moves the camera, edits, his focus on objects, his use of background paintings, red filters, and other simple tricks he must have learned in the silent era? His skill at telling a story visually remains on display, but it’s diluted by the absurd subject matter. I went into it hoping to be pleasantly surprised, but Marnie is impossible to swallow.

What in the film leads you to believe we’re asked to believe the characters live happily every after?

What in the film suggests to you that Rutland’s cure DOESN’T have exactly the negative psychological consequences you’d expect?

I feel like we watched different movies.

The ending is an unambiguously happy one. Marnie finally allowing herself to remember what happened that night as a child is shown as the cure to her woes. The happy couple leaves her mom’s apartment, they see the smiling happy children, and we pull back to a big wide shot. That’s a happy ending. Rutland is never presented as anything other than the firm hand Marnie needs to be cured.

Why did you feel the ending wasn’t a happy one where the problem was solved? What in the film suggests to you lasting negative consequences from Rutland’s actions?

Your conclusions are soo different. As I suspect it should be. Opinions come from peoples own experiences, perceptions and triggers. It’s like Rorschach’s blot test.