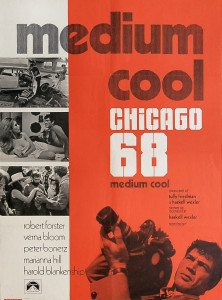

At the end of last year, cinematographer extraordinaire Haskell Wexler died. He left behind a imposing legacy that includes many SB4MC favorites. His eyes twinkled behind films from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest to Matewan. Directors including Hal Ashby, Norman Jewison, and Terrence Malick built their masterpieces upon Wexler’s clear-eyed vision. The man also, once, back in 1969, wrote and directed his own movie. That film is Medium Cool.

Medium Cool was ahead of its time and intimate to it and outside of it as well. That doesn’t make it a captivating watch, but it does make Wexler a visionary and his film a cultural artifact on the level of a smooth black monolith we might one day uncover on the moon.

Medium Cool was ahead of its time and intimate to it and outside of it as well. That doesn’t make it a captivating watch, but it does make Wexler a visionary and his film a cultural artifact on the level of a smooth black monolith we might one day uncover on the moon.

If you’ve found this piece of cinema, you might be ready to consider deeper levels of reality. Shall we trigger the alarm?

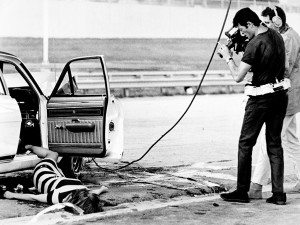

The film, Medium Cool, follows a foolishly young Robert Forster in the role of Channel 8 cameraman John Cassellis. Cassellis is callous, removed from his surroundings by layers of lens. To demonstrate this, the film starts with him and his sound man coming across a car accident. They film the wreckage, eventually panning down to the driver; a woman, dead it seems, but who’s got time to check? Once finished they call it in — mostly so a motorcyclist can be sent to fetch their fresh footage.

If you’ve seen Nightcrawler, perhaps bells will be ringing, but those bells will soon doppler out of easy recognition. Cassellis isn’t Lou Bloom and he isn’t necessarily anyone else either. This film surrounds him but isn’t about him; it’s about the lens and the layers of brittle glass between us and the world. Wexler intercuts his unfettered drama with documentary footage of national guardsmen quelling fake student riots, with verité-style scenes of conversations interrupted and unexplained, with flashbacks offering only poetic context and meaning. Sound and light travel through Medium Cool like impulses more than like a story.

It’s an art film at times. But Wexler’s aim isn’t hard to suss even if his construction is looping and pleading and less eye-opening than his work can be and has been. Beauty isn’t the point; beauty is the distance between us. So too is fear and violence.

Cassellis pushes off connection with the world as he dallies in sexual frivolities and goes about his business. His business being capturing the strife of 1968 Chicago as racial tensions simmer, Bobby Kennedy gets assassinated, and the Democratic National Convention looms. While the world tries to throw this cameraman off focus Wexler zooms in on a poor mother and son (Verna Bloom, whom you might recall as Mrs. Dean Wormer, and Harold Blankenship) whose lives intersect with Cassellis’.

Cassellis pushes off connection with the world as he dallies in sexual frivolities and goes about his business. His business being capturing the strife of 1968 Chicago as racial tensions simmer, Bobby Kennedy gets assassinated, and the Democratic National Convention looms. While the world tries to throw this cameraman off focus Wexler zooms in on a poor mother and son (Verna Bloom, whom you might recall as Mrs. Dean Wormer, and Harold Blankenship) whose lives intersect with Cassellis’.

They are the reality from whom our professional peeping tom cannot extricate himself. Wexler, however, does not bother with how or why. Things in Medium Cool just are. There is a comically typical hippie dance party (with music by The Mothers of Invention) and a complexly tense racial altercation both dropped into the film with no concern for developing narrative, only for suggesting context. Both scenes exist as if to say: here is the world, put down your camera and feel it with your own two hands.

Be alive.

Be here now.

And then in some way that makes as little sense as it needs to, our leads find themselves at the real riots that roiled the actual 1968 Democratic National Convention — riots Wexler anticipated and filmed, bringing the rawness of the real world into marriage with the conceits of his created one.

And then in some way that makes as little sense as it needs to, our leads find themselves at the real riots that roiled the actual 1968 Democratic National Convention — riots Wexler anticipated and filmed, bringing the rawness of the real world into marriage with the conceits of his created one.

This intermingling is what makes Medium Cool more.

I say this even though Haskell Wexler’s bluntly delivered thesis about the alienating power of filmed media never grows clearer or more potently delivered than it does in the film’s first few minutes. I say this because what watching Medium Cool to the end provides is the meta experience that filmmakers today still attempt to recreate. He hasn’t made a film in which real events provide a basis for story; he’s made a film in which real events envelop the story.

It is United 93 filmed on the plane as it goes down. It is The Act of Killing as it happens.

Haskell Wexler punches a hole through the glass, or tries to. Medium Cool‘s title coming, as it does, from Marshall McLuhan’s work which labels television a cool medium. By this McLuhan means that engaging with it requires more effort so as to “fill in the blanks” and connect.

In the end — to spoil it, if you haven’t watched it and plan to — our characters drive off in a news wagon only to hear on the radio of their own fatal crash. If you’d attempted even a cursory consideration of where the story was headed, you’d expect this. Since the film starts with Cassellis coldly facing life’s end in an auto accident, so it must end — although I expected the victim to be the boy. Wexler isn’t as dramatic as I am, though. In his only film, his protagonist must die because there is no growth or learning for men like this. Men removed, who increase our removal, achieve their aims.

It is Cassellis’ actions that bleed repercussions onto the boy and those like him. Innocents full of anger.

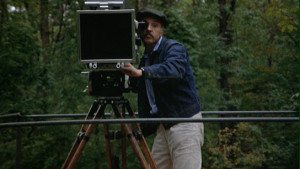

And then Wexler pans from the doppler-delayed crash to the passersby who witness without stopping and, panning on, to himself. Haskell Wexler behind his camera, filming the watchers and the wreck and then, finally, swiveling his camera to film you, the audience.

And then Wexler pans from the doppler-delayed crash to the passersby who witness without stopping and, panning on, to himself. Haskell Wexler behind his camera, filming the watchers and the wreck and then, finally, swiveling his camera to film you, the audience.

Tap the glass. See if you can get his attention. He might still be there.