In ten, or twenty, or a hundred years, the films you think of as essential will likely be forgotten.

That’s not to diss you or your taste; It’s just to say that the world moves on. For every Passion of Joan d’Arc and Soy Cuba which improbably retains its impact and small contingent of proponents throughout the decades, there are endless blockbusters and genre pictures — their initial popularity notwithstanding — that quietly fade into memory.

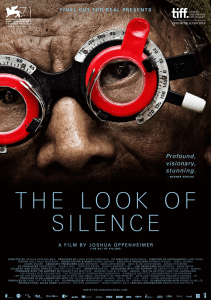

I bring this up because when you’re too elderly to remember the names of your children, people will likely still talk about and watch Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence and its precursor, The Act of Killing. These are both films that take a familiar medium and somehow — despite all earlier attempts — elevate that art form unto a higher plane of presence. They scrape the cholesterol from the hardened arteries of cinema, making its heart — and ours — beat with frightening vigor.

I bring this up because when you’re too elderly to remember the names of your children, people will likely still talk about and watch Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence and its precursor, The Act of Killing. These are both films that take a familiar medium and somehow — despite all earlier attempts — elevate that art form unto a higher plane of presence. They scrape the cholesterol from the hardened arteries of cinema, making its heart — and ours — beat with frightening vigor.

Your kids will watch these films. Their kids will watch these films. Everyone should watch these films. They are not cinema verité or documentaries; they are brain surgery and global psychotherapy. They are acceptance of hard truths and the healing that follows.

The Act of Killing takes us to Indonesia, where the perpetrators of a murderous 1965 purge of so-called communists — butcherers of hundreds of thousands of their neighbors — cheerfully remain in power. Oppenheimer and his co-directors (one anonymous and the other Christine Cynn) interview some of these men so that we might together relive and re-enact those glory days.

It does not sound like a fun film to watch, which is likely why you and most everyone else failed to see it.

Where The Act Killing escalates, however, is in the brutality not of what it describes, but in what it unveils before your very eyes. It is the brutality of long repressed emotional honesty. After two hours of hanging around with and reminiscing with mass murderers, one of them, Anwar Congo, on camera, for the first time, begins to sense that he is not a hero.

This film slowly, step by step, teaches a man who he is while you watch. It is a documentary made not for you, but for its main subject. We simply get to witness him travel through denial to doubt and then epiphany. His epiphany being that he has committed monstrous evil.

In his follow-up film, The Look of Silence, Oppenheimer continues down this road of on-camera psychological vivisection. We insinuate ourselves into the lives of a middle-aged Indonesian optometrist, purposefully unidentified with anything more than a first name, Adi. Adi’s older brother — labelled a communist — was pulled from his mother’s arms and brutally hacked apart fifty years ago. Now, as before, the perpetrators go about their lives, wealthy and esteemed and untroubled.

In his follow-up film, The Look of Silence, Oppenheimer continues down this road of on-camera psychological vivisection. We insinuate ourselves into the lives of a middle-aged Indonesian optometrist, purposefully unidentified with anything more than a first name, Adi. Adi’s older brother — labelled a communist — was pulled from his mother’s arms and brutally hacked apart fifty years ago. Now, as before, the perpetrators go about their lives, wealthy and esteemed and untroubled.

Except by this optometrist who does what most Indonesians wouldn’t dream. He, with all politeness, meets with his brother’s murderers and asks them if they have any regrets. While you watch.

It isn’t recreation or the capturing of events unfolding; it’s something else. It’s unpacking the self, in real time, in ways we are rarely challenged to do. Because we are not, I hope, men who have killed thousands, or siblings of a man who was butchered for what might be no reason at all. By those that still have the temerity to ask us for our vote and, even worse, get it.

The Look of Silence is a revelation of revelations. It is also a quiet, serene meditation. Oppenheimer doesn’t press, letting his camera rest on the drifting of cobwebs in the breeze, or on the lazy roll of light and mist. In this cricket-sung world, Adi watches footage captured earlier of his brother’s assailants as they re-enact his brother’s slaughter. The film is like a grotesquely evolved descendent of the Maysles’ documentary Gimme Shelter in that regard. Except in that earlier documentary, the Rolling Stones were little more than witnesses to tragedy and not its perpetrators or its victims.

In The Look of Silence, Adi watches with wrung emotions while monsters laugh and explain and flex their contented consciences.

Also swirling around are Adi’s parents — an elderly mother of indeterminate age and a blind and near-deaf father of 103 — who do their best to let the past be past. As if you can ever forget something like that. As if those wounds ever heal.

Also swirling around are Adi’s parents — an elderly mother of indeterminate age and a blind and near-deaf father of 103 — who do their best to let the past be past. As if you can ever forget something like that. As if those wounds ever heal.

Adi, we assume, knows they cannot and so he takes another road.

He visits with the men who killed his brother and sits with them and their families, as a guest or as a traveling doctor. He asks his hosts how they now feel about what they did. He asks not out of a desire for revenge, but out of a desire for closure and truth. They react to his unexpected and unwelcome inquiries with evasion, with threats and — lurking around the edges — the inkling of culpability and potential insanity.

No one denies that the killings took place. On the contrary, they gladly walk us through the specifics. What they won’t countenance is the idea that there was no communist threat or that the people they killed weren’t communists, or even bad people. Admitting those ideas into the world would be inextricable from admitting their inhumanity.

That they cannot do. They have drunk blood to stave off that madness. But we, and they, can watch the world around them as it begins to accept and understand what it must have always known. There is no dramatic outpouring, only a look of silence that is indelible and deafening.

For his part, Adi maintains composure. His brother died before he was born. The slaughter that filled the Snake River with bodies has washed clean long ago. And his motivation in pursuing what is clearly a dangerous line of inquiry isn’t unpacked, nor are the specifics of who his brother was or why he was included on the hit lists.

For his part, Adi maintains composure. His brother died before he was born. The slaughter that filled the Snake River with bodies has washed clean long ago. And his motivation in pursuing what is clearly a dangerous line of inquiry isn’t unpacked, nor are the specifics of who his brother was or why he was included on the hit lists.

These things do not matter. What matters in The Look of Silence is how we are in the face of what came before. Can we see and hear ourselves? Will we even ask the questions?

The Look of Silence does not contain the powerful denouement of The Act of Killing, but instead steadily pulses with smaller, additive revelations of awareness. It is, perhaps, a better film than its precursor, assuming you’ve seen them both.

And see them both is what you should do. It is what your children and their children should do. Because evil isn’t some big bad in a superhero movie; it is right here, shaking your hand, silent.

Amazing film. Just amazing.

I really need to see the first one.

Yes. It is mind-blowing and mandatory.