Few writers display a humor as dry as Charles Portis’s. If you’re not paying attention, it’ll fly right over you. In his later novels, like Masters of Atlantis, about a sort of low-rent Scientology-like religion, you can’t help but laugh, straight as the jokes are delivered, but in Portis’s second novel, True Grit, published to great acclaim in ’68, the humor is so sly it’s easy not to notice. Look harder. It’s all over the place.

Few writers display a humor as dry as Charles Portis’s. If you’re not paying attention, it’ll fly right over you. In his later novels, like Masters of Atlantis, about a sort of low-rent Scientology-like religion, you can’t help but laugh, straight as the jokes are delivered, but in Portis’s second novel, True Grit, published to great acclaim in ’68, the humor is so sly it’s easy not to notice. Look harder. It’s all over the place.

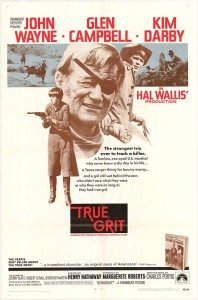

Watching the first film adaptation of True Grit, from ’69, one wonders if director Henry Hathaway is familiar with the concept of “humor.” His True Grit, scripted by Marguerite Roberts, is devoid of anything but the most obvious jokes. It’s a serious albeit uplifting movie likely to bore to death any but the most devoted John Wayne fans, of which I am not one. To be fair, it’s not Roberts’s fault. She’s so faithful to the novel, especially the dialogue, one might accuse her of sleeping on the job. The problem is in Hathaway’s direction. He has no idea which lines are funny. The movie is thus shot and edited to avoid anyone else having any idea, either. I watched amazed at how many lines taken directly from the book fell flat.

The entire movie falls flat. Though made in ’69, it’s a throwback to westerns of the ‘50s. There’s a reason I never liked westerns as a kid, and this is it. John Wayne is John Wayne, which isn’t the worst thing, but it’s a far cry from the best. Young Mattie Ross, whose story this is, is played by Kim Darby, who I know best from one of my least favorite Star Trek episodes, “Miri.” She’s just fine as the hard-headed seeker of revenge, but because this is an uplifting revenge flick in the hands of Hathaway, she lacks the uncompromising, unemotional affect of Mattie in the novel.

Given that the Coens’ ‘10 version of True Grit was billed as being more “true” to the novel, I was expecting the ’69 version to be a typical example of Hollywood tossing out the source material. But it’s the opposite. It’s an almost exact recreation of the novel, scene for scene. Dialogue is cut down, little bits and pieces are excised, various non-essential details are changed, but until the ending, it’s remarkably faithful, at least in terms of incident and dialogue.

Where the ’69 version fails is in tone. The lack of sly humor is one thing, but worse is the likeability of the characters. In Portis’s novel, nobody is likeable. They’re not necessarily unlikeable either. They’re straightforward in the extreme. They do what they do and that’s all they do and there’s something very appealing about it. Portis’s story is simple and direct in a way not easy to achieve. The movie takes his story and tries to fit it into a familiar cinematic language of the “old western,” resulting in a lot of flat lines and dull scenes, as though no one bothered to ask what anything they were doing meant. The less said about the loud, jaunty music, the better.

The few scenes original to the ’69 movie come at the end, in which young Mattie, her snakebit arm in a sling instead of amputated, reunites with Rooster Cogburn. Chatting with him in her family’s graveyard, she says there’s a spot for him too, when he dies. Aww. You just want to give these swell people a big hug. These swell murdering fools.

Portis isn’t about to say or even imply what one should read into his characters’ actions. They do what they do. The reader is left to decide what any of it might mean. His Mattie is a peculiarly hard-headed, so much so one must wonder at her wisdom. It’s fun to see this 14-year-old girl get the best of every man she meets, but she is in every way unreasonable, and dead-set on one thing: finding and killing Tom Chaney, the man who murdered her father. The result of her quest is his death, yes, but also the loss of her arm. She shoots him, but the gun’s recoil knocks her into a cavern, in which a snake bites her hand. She narrates the story as an adult. She never married and has seemingly no interests outside of her religious devotion and her bank. Did her quest for revenge ruin her life? Did her religious belief steer her wrong? Is she driven only by her love of money? I think one must at least entertain theses questions.

The ’69 movie has no interest in any such thoughts. It is the tale of a tough girl exacting a rightful revenge with the help of a cantakerous but friendly old U.S. Marshall and a Texas Ranger, with a happy ending.

What about the ’10 version? Is it more true to the vibe of the book? I’m not sure that it is. Both movies are true to the novel in different ways, but neither one captures the novel’s spirit.

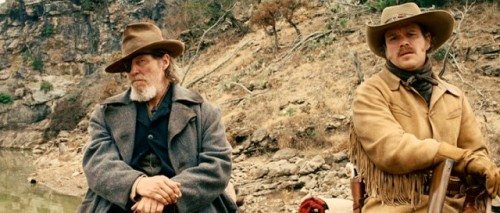

The Coens, of course, are the Coens. Their True Grit is a lovingly shot movie with some stellar performances. But it too shies away from the blunt and simple directness of Portis’s novel. The Coens invent scenes left and right in their version. They cut scenes and re-structure others. The Texas Ranger, LaBoeuf (Matt Damon), is given a brand-new dramatic arc, and toward the end, just prior to Mattie meeting Chaney (Josh Brolin) in the river, a classic “end of act two” scene is inserted in which Cogburn (Jeff Bridges) angrily tells Mattie he’s done with her and with Chaney and will be leaving them in the morning. LaBoeuf, too, rides off, claiming the trail is cold. Oh no! The team has split up! Is all lost? Will they never succeed?

Coming from the Coens, this kind of jazzed up faux drama feels especially galling. Roberts and Hathaway trusted Portis without understanding him, whereas the Coens understand him but figure his dramatics need a goose. They can’t help heightening the emotions. It’s natural in a movie, yet the lack of underlined emotions is the key to the novel. It’s the very source of the novel’s power. Portis conjures up emotional resonance by excising all emotion. This is no easy trick.

The Coens try to capture this at the end of the movie, which unlike the ’69 version adheres to the novel. Mattie’s shy one arm, and 25 years after losing it makes a trip to a traveling old west show in which Cogburn is performing. She just missed him, she’s told. He died three days prior. She has his body buried in her family plot.

The violence in the novel is blunt, and the Coens include more of it than does the ’69 version. But not much more. I was surprised to see Moon’s fingers lopped off in the earlier film. Moon, by the by, being played by Dennis Hopper to far greater effect than Domhnall Gleeson in the later version.

But despite a slight increase in blood, the Coens bathe their old west in gold and orange. The score by Carter Burwell is soft and elegiac. It’s a warm movie about cold characters never allowed to appear as cold as their actions belie.

Even forgetting the book comparison, the Coens’ version, which I watched again for the first time since it came out, has an odd feel to it, tonally. It’s pleasant enough, with a lot of delicious, old-timey dialogue, but not especially involving. Bridges is great as Cogburn, and so is young actress Hailee Steinfeld as Mattie. Damon isn’t bad, and Brolin is fun as the dim-witted Chaney. It’s an improvement over the earlier version, and still it’s lacking.

The book was written in ’68, a prime period for revisionist and acid westerns. If any director was born to make a movie of True Grit, it was Monte Hellman. Imagine if he’d worked with this material around the time he made Two-Lane Blacktop. Nothing underlined, no overwrought characters, no juiced up drama. Just straightforward people doing what they do. It’s why the story works. Hathaway and the Coens mean well, and that’s just the problem. They mean too well.

I am a huge fan of Westerns and John Wayne and I never liked either film of True Grit. I thought the Coen’s remake was pointless when I saw it and the Wayne version some odd cross between an episode of the Waltons and another, worse, episode of the Waltons.

Yep, that about sums it up. Good book, though.

I read this book and re-watched the ’69 film recently as well, but have yet to re-watch the Coen Bros. film. I couldn’t make it all the way through the original movie in one sitting. I watched in bits and pieces, out of curiosity. I thought that John Wayne was actually a good choice for Cogburn – he played an unlikable lead in The Searchers, so I think he could have had a similar effect here, but yeah, his character winds up being just kind of a shmalzy curmudgeon.

The main difficulty in adapting this book might be the narrative voice of Mattie. Reading it from her perspective, it’s easier to believe, admire, and yet, as a detached reader, still question her hard-hearted precociousness. Without being able to see the story through her eyes, capturing the tone is all the more difficult. European filmmakers capture this tone more often. The folks who made A Pigeon Sat on a Branch should take a stab at it.

Now that is a surreal notion. And so I am in love with it. “The Grit, Truly,” they could call it.