Does the Internet dream of itself? This tag line for Werner Herzog’s new documentary could hardly have been more alluring, and as it stared up at me from my program while waiting in the ticket line at Sundance HQ, I silently implored every person in front of me to buy passes to something else. Every few minutes a staffer came out with a dreaded red dot sticker to mark another screening as sold out, and each occasion was a source of tremendous anxiety. Kelly Reichardt’s new feature Certain Women was also atop my list, as was a German documentary on Frank Zappa, and I started wondering what the chances were of sudden illness breaking out amongst those ahead of me—or perhaps spontaneous combustion?

I arrived excited to support The Bad Kids, a feature doc I edited with Mary Lampson that took a prize in the US Documentary Competition, but was sure in the belief that I would keep my head and remain immune to the Sundance hype. Fat chance! There is something electric about a festival that offers World Premieres of every single title, and as the lights go down on a new screening and the director introduces their work, the stakes feel like they couldn’t be higher…

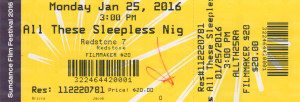

My ticket to transcendence

Why? Well, seeing the new Star Wars on opening night is fun, but there’s a limit to the power of a highly processed commercial product that is also being viewed by a zillion other people at the same time in multiplexes across the land. At Sundance each screening is the occasion for something of genuine artistic value to reach its public for the very first time, and this creates a palpable sense of connection between audience and film. Waiting in that ticket line, it really feels like each of those precious little slips of watermarked card stock may hold the key to transcendence.

I placed my lot on a half dozen films. How did they measure up to this impossible standard? Read on.

LO AND BEHOLD: REVERIES OF THE CONNECTED WORLD

Werner Herzog’s unique brand of filmmaking has always illuminated the beauty and the horror of the world in unexpected ways, and it seemed plausible that he might be the perfect person to make a film about what technology has done to our sense of our own humanity. Indeed, as he introduced the film at the Mark Theatre for the film’s World Premiere, he offered that he did not own a cell phone, and other comments suggested a deeply skeptical attitude toward the wired world.

What unspooled for the next hour and a half was, by comparison, rather tame. Far from a coherent statement, the film is a grab bag of ideas and explorations, some mildly profound, some mundane. Herzog interviews hacker legend Kevin Mitnick, who spills some details from his exploits. We learn that the electromagnetic disruption caused by solar flares has the potential to bring down all of earth’s communications equipment in one cataclysmic swoop. We hear from Elon Musk about his SpaceX endeavors.

The overall effect is not unpleasant. Lots of crazy smart people musing about the intricacies of the connected world is not a bad way to spend 90 minutes. But some of the most enjoyable moments feel accidental rather than planned, and usually come from Herzog’s talent for spewing extreme and semi-random comments on his way to a bigger idea. One of his first lines of narration—heard over shots of a sterile institutional building at UCLA—reads, “in this disgusting hallway, the history of the Internet is hidden…” Immediate laugh line! But that bold take on the aesthetics of the décor is not on offer in his dissection of future trends elsewhere in the film. Sure, he valorizes the person-to-person contact that results from living in a community with no cell phone towers or internet service, and he mildly questions the oddity of robots becoming more and more convincing as human companions, but there is nothing truly new here. Give this film two years and it will feel dated.

It’s also exceedingly conventional in terms of style. The images are blandly functional (talking head interviews mixed with moments of verité), and I can think of only one shot that was truly cinematic: an exceedingly uncomfortable tableau of the family of a girl whose fatal car crash was caught on camera and became a viral video sensation. (Herzog sets them up in a stiff, formal setting as they all look directly at the camera, an untouched brunch spread sitting awkwardly in front of them.) And it did not surprise me to learn that the film was first birthed as a series of web shorts, as its 10-part “chapter” structure mostly failed to create a sum that was greater than its individual parts.

The crowd cared about all these limitations not a whit. The film received generous applause when it concluded, and when Herzog came onstage for the Q&A he uttered a few more unscripted zingers . “Now, let’s say I hang myself from that beam up there, and then I need a second support from the side to stabilize my dead body, and a third one below wrapped around my feet,” he said at one point when making an odd analogy about the architecture of the internet. “Think about a world with no women,” he exclaimed in another riff. “It would be unbearable!” Maybe the crowd was right. Even second rate Herzog merits a second look.

CERTAIN WOMEN

Kelly Reichardt’s slow, patient films are arguably just what a world overrun with high octane distraction needs, and this latest offering did not disappoint. Laura Dern, Michelle Williams and Kristin Stewart all play Montana women navigating the everyday challenges of their lives, and though the three stories only intersect in cursory ways the film feels completely of a piece as a wonderfully subtle piece of feminist filmmaking. In Reichardt’s vision, the wind and the skies are nearly as important as the narrative itself, as its mildly desaturated tones convey something unmistakable about the limitations that the characters face.

Certain Women may have made Herzog’s intended point about the perils of the internet better than Herzog himself, and it was fascinating to see Reichardt navigate the room in the post-screening Q&A as she repeatedly pleaded with the crowd to put down their cell phone cameras and “just have a conversation, right here.” (Stewart’s presence on the stage may have had something to do with the number of attendees hoping to snap a pic.) This is a film of subtle pleasures that makes you appreciate the contours of the physical and social spaces that each of us inhabit in our daily lives. Recommended!

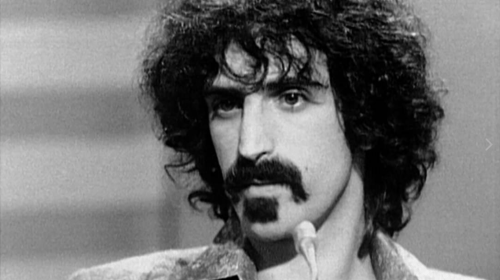

EAT THAT QUESTION: FRANK ZAPPA IN HIS OWN WORDS

Emphatically not a feminist, Frank Zappa was a musician perpetually at war with his own image. A longhaired troublemaker who famously scorned drink and drugs, and who referred to himself as a “conservative,” his music was uncategorizable. Was he a jazz musician? An experimental New Classical composer? A lazy songwriter whose most famous hit was the novelty song “Valley Girl”?

German filmmaker Thorsten Schütte spent years sifting through a trove of archival material made available with the cooperation of the Zappa family trust, and this goes a long way toward showing the logic behind Zappa’s seemingly contradictory actions.

Opening with a clip of a mild-mannered Zappa in suit and tie appearing on the Steve Allen Show in 1963 sets him up as an intelligent man hoping to open his audience’s mind to new sonic adventures. Is he an “icon” or an “iconoclast”? No, he’s a serious individual who uses a bicycle as an instrument.

Many of Zappa’s rants about the rapaciousness of the music industry and the utter stupidity of the American political establishment are legendary, but in this film one gets a new sense of the source of the man’s outrage. Zappa wanted to challenge his audience and to create art that was unique and difficult. He saw America’s unwillingness to properly fund public art as a catastrophe, and looked at the music business as a rapacious beast intent on dumbing down the tastes of the public to an easily exploitable common denominator. (More than one televised debate shows him chewing apart adversaries.) What made him most mad, it seems, was that public figures in American life did not ask more out of those who they represented.

His personal life is touched on here in only cursory ways and Schütte’s point of view is openly adoring, so Zappa’s tendency to wave the First Amendment flag when people objected to casual lyrics about rape is not given serious scrutiny. Given Moon Zappa’s characterization of her father on Marc Maron’s WTF interview, I had assumed that Frank wasn’t much of a father, either. But Moon and two of her siblings were there for the screening (Dweezl, on tour playing Frank’s music, could not make it) and they clearly relished the serious attention given to their father. Son Ahmet chatted afterward about how his dad asked him to think for himself and to follow his own muse.

A real treat for fans and possibly others, this one was picked up by Sony Classics and will be out later this year.

HOLY HELL

Craziest film I saw at Sundance. Not the best made, not the most original, but the one with the raw material that packed the most punch. Long story short, director Will Allen joined a secretive cult 20 years ago when he was fresh out of college, and quickly became the group’s resident filmmaker. As the years wore on and Allen’s ties to his biological family diminished, the cult’s leader “Michal” became more and more strange. Holy Hell is Allen’s memoir, and his attempt to understand what happened to him and his fellow followers as they bought in to the leader’s BS and then later tried to get out. What you see in this film is one of the more creepy and bizarre megalomaniacs you will ever encounter on camera, and one comes close to understanding why his devoted followers wanted so badly to believe that they put up with mental, physical, and sexual abuse from him on a regular basis.

When Allen brought out many of his compatriots as the lights went up, the crowd roared in an outpouring of sympathy. Many had extracted themselves from the group only recently, and others had just seen the film for the first time. It was incredible to see their reactions to the material, and to have them re-engage with “reality” as if before our eyes. It was an intensely moving experience, because these people were not “crazy” at all—they were normal human beings who found such meaning in the sense of community that the group offered that they spent decades being willfully blind to the deeds of its leader.

The sheer shock value in this film is enough to get you in the door, but it also has something unique to offer about the nature of belief and the very human desire for love and connection.

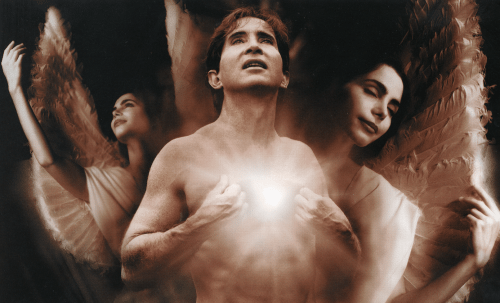

ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS

If there’s one film I saw at Sundance that really took me somewhere, it was this one. It was full of flaws, and I spent the first 15 minutes trying to decide whether or not I despised the main character, but before I knew it the end credits were rolling and I was very sad to be sitting in a movie theatre again rather than floating through the streets of Warsaw.

Polish director Michal Marczak devised his own Steadicam-style camera rig to follow Kris and Michal, a pair of young 20-somethings exploring life, love, and the nascent rave subculture in Warsaw over a long summer. What results is a dreamy, sensuous, unapologetically hedonistic film that spends a lot of time just watching its subjects move from place to place. On paper it may sound insufferable—and to some audiences that will surely be the case—but I found it electrifying. Do you remember what it was like to be 23 and hungry for life? This film will take you back there.

The plot involves a couple of love triangles that develop and break apart, but this is completely beside the point. More relevant is the floating, languid camera work that documents the increasingly intuitive way that protagonist Michal is able to move to the irresistible mid-tempo EDM beats that flow through the film. In the early scenes the music feels like it’s external to him, and he’s intrigued but misunderstands it. As the film goes on and he discovers his body, the music gets inside of him.

Do these words make any sense at all? They might if you were on the drugs that these kids are taking, but short of that the next best thing would be to find a way to see this film.

DAZED AND CONFUSED WITH LIVE COMMENTARY BY RICHARD LINKLATER

Linklater introducing Dazed and Confused

As I made my way back to Headquarters on a cold Park City morning a couple days later, the line was already snaking around the corridors of the Marriot ahead of its 8am opening. I knew I had come too late, and I feared the worst: by the time I made my way to spitting distance of the counter, passes to Dazed and Confused with live commentary by Richard Linklater would be gone. This was rumored to be the second-hottest ticket of the festival (the first being Nate Parker’s Birth Of A Nation), and I was surprised that the red dot lady hadn’t yet blotted it out on the schedule. I waited, anticipation high.

And then it happened: the lady appeared, nudged by me apologetically, and slowly peeled the little red sticker off of its backing and onto… Dazed and Confused. Thus, dear reader, I cannot report on it for you here. (Check out Mashable’s report if you

please.)

I had already been lucky. Lucky to be here, lucky to be seeing films with other lovers of film, lucky to have tasted traces of the transcendence I had come for. I tried to keep things in perspective as I sidled up to the counter and picked out a handful of fresh yellow tickets, eager to see what the next couple of days would bring.

Og usually goes by the name Jacob Bricca. He teaches filmmaking at the University of Arizona and also directs and edits documentaries. You have seen his work if you’ve watched Lost in La Mancha or stumbled upon his ode to action movie clichés, Pure. His latest film Finding Tatanka will be released on DVD soon.