There are two ways to present supernatural terrors in movies. The most common way is to present the terrors as real, and act accordingly. The less common way, generally seen in smaller, artier, more thoughtful movies, is to have the reality of the terrors open to debate, and thus focus on the madness of believers.

There are two ways to present supernatural terrors in movies. The most common way is to present the terrors as real, and act accordingly. The less common way, generally seen in smaller, artier, more thoughtful movies, is to have the reality of the terrors open to debate, and thus focus on the madness of believers.

Poltergeist is an example of the first kind. There are in fact bodies buried under the housing development, and there are in fact any number of disgruntled spirits ensorceling meat, clowns, and trees. The family’s reactions to the supernatural are therefore perfectly sensible. They are not freaking out over the imagined. Poltergeist is not a tale of madness. It’s an object lesson in why never to move only the headstones.

The Shining is an example of the second kind. Whether or not the hotel is possessed with the freaky spirits of those who’ve died within its walls is open to debate. Is Jack driven to murder by ghosts? Or by his own addled brain? Stephen King thinks it’s ghosts, but Kubrick has other ideas. Ambiguity is what makes The Shining as powerful as it is. Nothing is explained. You’re forced to make sense of it, or fail to, on your own.

The Witch, a new movie by first time writer/director Robert Eggers, wants it both ways, and suffers for it.

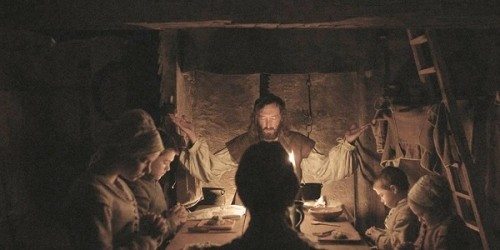

Set in the New England of the 1600s, The Witch features an excellent sense of time and place, with sets made using tools and materials actual settlers would have had access to, and dialogue taken in part from diaries of the era. Eggers admits to being obsessed with details. His witches are inspired by real accounts of the era, as well as, notably, the 1922 Danish silent sort-of documentary, Häxan: Witchcraft Through The Ages, a dispassionate account of Satanic superstitions full of wild visuals (check it out sometime, the depiction of Satan alone is worth it).

As the movie opens, we’re thrown into the woods when self-appointed Puritan preacher William (Ralph Ineson) and his family are booted out of the settlement to fend for themselves. No sooner do they set up house than their new baby is whisked away under the eyes of teen daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy). Lest we wonder at what happened, we catch up with a witch in her woodsy hovel, where she dices up the baby into a bloody mush she smears over her naked body and her broomstick, upon which she rises slowly into the night.

So in the first five minutes we learn that the witch is real in The Witch. We don’t see her through the eyes of one of the characters. There’s no ambiguity here. Eggers intends to bring us back to a time when witches were real. There’s nothing postmodern going on, no examinion of oppressive religions doing what they will to women, no suggestion of wheat ergot causing mass hallucinations. There is a witch in the woods, and she stole and killed a baby.

In supernatual movies where the supernatural is real, one expects to experience a healthy dose of the supernatural. The Witch is, curiously, uninterested in showing us witchcraft after its intial witchy murder. The witch appears once mid-movie, red-caped and seductive, and again in a very witchy final scene. But the rest of the movie plays out as though the reality of witches is up for debate. The family—their crops cursed, their baby stolen, and other indignities to come—fractures. William maintains (or loses?) his sanity by obsessively chopping wood, his wife, Katherine (Kate Dickie), is inconsolate over her vanished child, the young boy, Caleb (Harvery Scrimshaw), sneaks off to the woods with Thomasin and encounters a demonic bunny, and the young twins run around taunting the goats and creeping everyone the fuck out.

Are they going crazy, or is there really a witch out there? we might expect to be asking of a movie playing out thus. But, no, there’s definitely a witch out there. So while plenty of slow-paced eerie scenes play out, they key word is slow. We know more than the characters do. The Witch is not at all a scary movie. Creepy, yes, with atmosphere to spare and a little blood now and again, but mostly it’s a noose slowly tightening.

It’s a very literal movie. Nothing is unknown. To me, the unknown is the scary part. Once I know there’s a witch in the woods, the only way to freak me out is to see the witch in action. The Witch isn’t interested in this. It’s interested in the family falling apart, which, again, would be considerably more powerful if they didn’t have a perfectly good reason for falling apart.

“Faced with a horrifying demonic monster out to destroy them, the family fell apart,” while not a bad story to tell, has much less to say about the human condition than “Faced with the possibility of a horrifying demonic monster out to destroy them, the family fell apart.”

Another way to look at witchcraft is through the lens of female empowerment. Maybe, in this long ago era, given the “reality” of witches, the only way for a woman to control her destiny is to embrace witchcraft. Perhaps the movie wants to suggest this with Thomasin’s fate. Yet this is again hampered by the movie’s strict adherence to the beliefs of the times. Because witches, as seen then, do not act of their own will. They are controlled—created, even—by Satan, a male demon. So it is in The Witch.

We’re back to the simple and the literal. This is what The Witch offers. It’s shot with utterly flat light. Nothing pops. The woods, the Puritans’ home, the people, everyone blends together in a kind of ominous colorlessness. Not a cinematic look I’m fond of, but it seems to be the style these days, and at least in this case it fits the mood of the piece.

Despite it never really connecting with me, The Witch is an impressive debut by Eggers. I’ll be interested to see what he comes up with next. Maybe it’ll get under my skin more than The Witch.

I am glad I read this review instead of seeing The Witch. It will join the ranks of other well-received horror films I mean to see but yet somehow never do.

Maybe next year.

It’s no Babadook, that’s for sure. But yeah, it’d be reasonably diverting some future night on your TV.