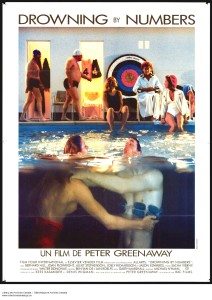

Drowning By Numbers (’88) is a fairy tale of murder and numbers. It’s a showcase of writer/director Peter Greenaway’s obsession with decay and order, with numerical games, with precision, formalism, abstraction, with earthiness, sex, and death. It’s a very weird movie. I liked it.

Drowning By Numbers (’88) is a fairy tale of murder and numbers. It’s a showcase of writer/director Peter Greenaway’s obsession with decay and order, with numerical games, with precision, formalism, abstraction, with earthiness, sex, and death. It’s a very weird movie. I liked it.

I hadn’t seen it since it first opened. I remembered nothing but the basic plot—three generations of women drown their husbands—and the numbers 1 through 100 appearing (visually or verbally) sequentially throughout the film. What I couldn’t have known then but was slapped in the face with now is how much of a debt Wes Anderson’s style owes to Greenaway. But where Anderson is twee and darling with a dollhouse aesthetic to his lovingly designed and shot sets, Greenaway, no less precise, no less fascinated by center-framed tableaux, plunges into the earthiness of sex and death and decay in a way totally alien to Anderson. Greenaway is like the lecherous old satyr to Anderson’s innocent wide-eyed child.

The film opens with counting. The Skipping Girl is jumping her neon rope and counting off the stars in the sky and naming every one. She stops at 100. Why? “Once you’ve counted to a hundred, all the other hundreds are the same.” When, toward the end, she’s hit by a car and killed, it’s funny, but only because you don’t know she’s dead yet. It’s less funny when her death inspires suicidal thoughts in young Smut, a boy obsessed with counting everything in the world, from bees to leaves on trees to roadkill to hairs on his head. To Smut, counting is a game. Everything is a game.

Smut describes many of his games, the most complicated by far being Hangman’s Cricket, a game the rules of which take players an entire day to learn. My personal favorite is Sheep And Tides, wherein a grid of nine sheep, standing in ankle deep water, are tied to chairs upon which tea cups and saucers are set. As sheep, we are told, have particular sensitivity to the tides, they will, when the waters rise, move, thus jangling the tea cups. Players each select three sheep in a row and win when their sheep are first to jangle their cups. A full game is played over twenty-four hours and three changes in the tides. Sounds like fun!

Threes, then. Very important in Drowning By Numbers. There are three women each named Cissie Colpitts, the grandmother (Joan Plowright), the daughter (Juliet Stevenson), and the niece (Joely Richardson). The first two are married, the third engaged. The movie opens with the eldest Cissie’s husband, Jake, drunkenly cavorting with a younger woman, Nancy, in a pair of metal bathtubs in a sort of gardener’s shed in back of the house. The room is decorated as is every one of Greenaway’s rooms, with a purposeful mess precisely arranged. It’s a still-life of chaos, representing the inevitable order of decay. During the couple’s fling, and during the subsequent drowning of Jake, Greenaway includes multiple cut-aways to close-ups of butterflies flapping on and snails crawling over fruit and flowers and other detritus, as though 16th Century still-lifes had come to slowly rotting life.

Once the deed is done, Cissie asks local coronor Madgett (Bernard Hill, whom you know best as King Théoden) to report the death as accidental. He’s rather torn up about it, but goes along with it in the hopes of sleeping with her.

Cissie and the other Cissies talk about the drowning and talk about their own men and generally just have a good time of it in a way you don’t often get to see women having a good time in movies. Drowning By Numbers is very female-centric. The men are either expendable or, in ways subtle and not so subtle, laughable.

The drowned Jake’s fat twin nephews arrive in town, suspicious of Cissie, and get together with Jake’s fling, Nancy, at the watertower. The Cissies realize their story is being questioned, but that doesn’t stop Cissie the second from drowning her husband in the ocean. Once again Madgett covers it up, and once again he tries to get in the pants of the killer. She puts him off as did her mother.

Once young Cissie marries her beau, Bellamy, a known non-swimmer, you know where things are heading. Their marriage lasts a mere three weeks.

Drowning By Numbers might be said to play out as one movie three times. Yet it’s weirder than that. It’s almost like a murder mystery where everyone knows the identity of the killers, with drama provided not by an investigation but by the sequentially appearing numbers. Waiting for the the next one to appear creates a kind of suspense.

The numbers are often written, sometimes spoken. Three of them appear on runner’s jerseys. Two are painted on bees. I missed some, but most are easy to spot. When 100 arrives, it’s in the last shot of the film, the scene of the final death.

Death is the prime subject of Drowning By Numbers. The murders, the lonely life of the coronor, Smut’s obsession with counting dead animals and launching a firework for every one. Death is but another part of nature. Should we be so concerned with these three murderers?

Much of the movie takes place outdoors, yet Greenaway isn’t remotely interested in featuring natural light. He lights every scene with multiple sources. Shadows spread out in every direction. Interior lit cars seem to float through darkened landscapes and mysterious fogs often loom in backgrounds. The result is something fantastical and adds to the fairy tale tone.

The pleasures of Greenaway’s best movies—of which this is one—are often not the pleasures of normal movies. In this case, the characters exist at a remove from real life. You don’t come away emotionally attached to anyone. Greenaway poses people as do painters. He is an observer of his meticulous worlds. When he does it well, his tableaux throb with life, even when his characters are thinking of nothing but death. Greenaway is like Smut with his obsessive numbering, and like Madgett, fascinated by the dead. Madgett proposes writing a book about every cricket player who’s died during a game, his research for which includes taking photos of Smut wearing only underwear, cricket bat in hand, and colored electrical tape marking points of injury. That’s Greenaway in a nutshell: meticulously arranging and photographing his obsessions for our amusement.

I think it is time for me to give Greenway another shot. I’ve seen a bunch, but never quite digested any of them. Too young, probably.

This is a good place to start. I saw it at the Roxie, not sure how readily available it is otherwise.

I think his best movie is The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. Otherwise, the earlier ones are generally more watchable. Like Belly of An Architect and The Draughtman’s Contract.