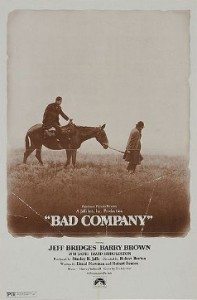

Robert Benton’s 1972 revisionist Western Bad Company is anything but. Slow and unsteady it may be, but that doesn’t keep the film from endearing itself to you like a young, delinquent Jeff Bridges — bangs a flopping and lips a flapping.

Robert Benton’s 1972 revisionist Western Bad Company is anything but. Slow and unsteady it may be, but that doesn’t keep the film from endearing itself to you like a young, delinquent Jeff Bridges — bangs a flopping and lips a flapping.

But take care for the company you keep, as it’s likely to corrupt. Unless you’re already corrupted and didn’t realize it. Which, hey, don’t let me burst your bubble.

Benton, who’s best known as the writer of Bonnie and Clyde, Superman, and Places in the Heart (most with partner David Newman), here makes his directorial debut, and it’s a beaut. The kind of beaut that will break your heart without you even realizing it.

Bad company might just be what you need and what you are. It’s also likely what you’ll get if you do something as foolish as chase your fool dreams.

Shot by Gordon Willis in lonely, collapsed monochrome, the story starts by forcibly rounding up reluctant recruits for the Union Army. Drew (Barry Brown) evades enlistment, receives $100 and his dead brother’s gold watch from his upstanding Methodist family, and flees west. In Missouri he runs into Jeff Bridges, playing Jake Rumsey. Bridges — fresh off of Fat City and The Last Picture Show — looks like a bag of wet feathers, but he’s the britches-hitched-up leader of a gang of barely pubescent ne’er-do-wells. He mugs Drew and makes off with his pocket cash.

So that we get a story, and the one we deserve, Drew and Jake quickly reunite in such a fashion that leads them to throw in together. Their plan — along with the Logan brothers, twitchy Arthur, and ten-year-old Boog — is to steal enough loot to fund their journey out West. Drew silently vows to retain his just ways, faking his share of the criminal activity, while Jake talks as big a game as he can fit from between his lips.

The whole thing, from its first moments, is a hot mess wrapped in cold, congealed chicken fat. The boys don’t know the first thing about being criminals, or survival, or even each other. For all his talk, Jake is barely more able than Boog. And when things start going wrong — which is right away — they don’t do so gently.

Far be it from me to narrate the events that befall these seemingly mismatched man-children. Some are cleverly played, others are dark and rough, and others still involve the under-sung Geoffrey Lewis and the big Lebowski himself, David Huddleston. Let us just say that Bad Company is not a film of white-hatted heroes riding off into the sunset. It is a film about the lousy lot who’ll remain by your side, regardless of how rotten you are down deep.

As Drew and Jake come to terms with who they are and aren’t, Benton and Newman’s unsparing script scrapes its filthy fingernails along the underside of your neck. Look up, it says. It could be worse. You could be this weak and willing all on your lonesome.

Bad Company will end abruptly. You’ll shrug your shoulders and decline to take a firm stand as to your opinions of it. But as you slumber its misty tendrils will cloud your mind. You’ll awake with an unshowered suspicion that you’ve seen something more, that Bad Company could be something more.

Although it might be lying.

I had never heard of this film before finding it here. I saw it three months ago and still think about it frequently.

Sometimes, it’s the quiet ones. Glad to steer you right, Pike.