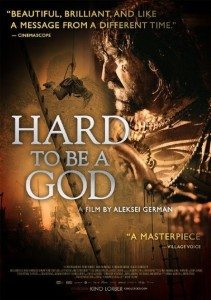

A three hour, filth-covered travelogue to the middle ages, the Russian Hard To Be A God (Trudno Byt Bogom) is not a normal movie. It’s dark, strange, oppressively claustrophobic, bloody, sweaty and wallowing in human misery. It has a story buried under the Terry Gilliam-meets-Peter Greenaway production design, but good luck winnowing it out. I read the book it’s based on a month before watching the movie, and I could barely discern characters or story. It’s less like a movie and more like being immersed—dipped, let’s say—into a vat of blood and muck, and left there for so long you forget another reality ever existed.

A three hour, filth-covered travelogue to the middle ages, the Russian Hard To Be A God (Trudno Byt Bogom) is not a normal movie. It’s dark, strange, oppressively claustrophobic, bloody, sweaty and wallowing in human misery. It has a story buried under the Terry Gilliam-meets-Peter Greenaway production design, but good luck winnowing it out. I read the book it’s based on a month before watching the movie, and I could barely discern characters or story. It’s less like a movie and more like being immersed—dipped, let’s say—into a vat of blood and muck, and left there for so long you forget another reality ever existed.

It’s shot in intense, crisp black and white, and thank god for that. All the guts and shit and mud would be overwhelming in color. Director Aleksei German’s camera never rests. It’s in constant movement, shoved into faces, asses, animals, garbage, then wandering on, either following Don Rumata (Leonid Yarmolnik), or representing his point of view. Weird goggle-eyed grotesques wandering past the camera regularly look directly at it, destabilizing the viewer yet more. Are they looking at Don Rumata or at us? And if at us, who are we? A film audience? Or Rumata’s rulers back on Earth?

Hard To Be A God is a science fiction story, though visually you’d never guess, based on the book of the same name by Russian sci-fi writers Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, best known for their novel Roadside Picnic, famously adapted by Tarkovsky in 1979 as Stalker. The middle ages nightmare we’re plunged into isn’t on Earth, it’s on an almost identical neighboring planet stuck some 800 years behind Earth’s development. From Earth some thirty scientists are sent to the planet, to the kingdom of Arkanar, to observe and report. They are not to influence developments in any way, and they may not kill anyone. With his abnormally strong armor and future fighting skills, Rumata is known far and wide as the greatest swordsman. Though he’s never lost a duel, he never kills the defeated, only cuts off their ears. Which hurts a lot, he explains.

This sci-fi set-up isn’t seen, it’s related in voice-over. We’re thrown into the muck from the first frame, and only let out three hours later. The novel features a futuristic helicopter rescuing Rumata late in the story. Not so the movie. Rumata might be from another planet, but you’d only guess it by his attitude. He’s both a part of this dirty age and far above it, making his way through the absurd, ugly madness as if he can do anything, as if nothing can touch him. But though he fears no one, this world does touch him. It drags him down to its level. It’s hard to be a god.

Scenes are long and winding, many made up of single shots. Hands and other objects are often thrust before the camera, if it’s not banging into them on its own. Every inch of the screen is packed tight with crap, sometimes literally. There’s no escape from this world while you’re in it, no rising above it, no viewing it from an outsider’s perspective. Once you’re here, you’re here. A potent metaphor.

German died before Hard To Be A God was finished (in ’13). Though a huge figure in Russian cinema for many years, he’s not well known in the west. This is the first of his movies I’ve seen. He started shooting Hard To Be A God in ’00, though it’s said he first wrote a draft of the script as early as ’68. He finished shooting in ’06. The six or seven years following he spent perfecting it, though with his death it had to be completed by his wife and son. The resulting film is not quite like anything else. It’s amazing for the world it creates. But as far as telling a story, it has little interest. It’s not an easy movie to watch. It both hypnotizes and repels.

The novel likewise suffers from a lack of incident. It feels like the authors were more interesting in creating a world than relating a story set within it. Nevertheless, a story emerges, and even gets exciting by the end. German, in his adaptation, seems totally unconcerned with drama. The meandering scenes are hard to hold on to or make sense of in dramatic terms. If characters want anything, it’s hard to know what. From reading the book, I knew Rumata was at odds with Don Reba, and was interested in saving the life of an important doctor, one of the many scientific and artistic men being systematically killed by the greys, the soldiers of Don Reba. In the movie, the doctor appears, but he turns out to be as backwards as anyone else.

Don Reba appears too, though I wasn’t sure it was him. Names are infrequently spoken, faces blend together, costumes reveal little about stature, such that I was rarely certain of who anyone was aside from our hero, Rumata. I watched Hard To Be A God in a kind of trance, not knowing what was happening or why, but feeling an intense sense of purpose behind it. It’s all supposed be happening the way it’s happening, you can tell that much, it’s just what is happening that remains foggy. And muddy. And bloody.

And in many cases, beautiful. It’s a movie packed with stunning images. Toward the end, once the blacks, a creepy religious order, have ousted the greys, Rumata defies his orders and gears up to kill. He wears a horned helmet and mask and in a series of misty images looks like a monstrous beetle preparing for battle. With an ever-moving camera, these moments of abstract beauty are short-lived, and all the more striking for it.

I admit I’m not sure whether or not I liked Hard To Be A God. “Like” is surely the wrong word, the wrong concept, to use with it. It’s its own thing, that much is certain. I’ve been thinking about it for days since watching it. It’s wormed its way inside my head in a way few movies do. And I can’t imagine ever watching it again. Would I recommend it? Not to the faint of heart. Watch at your own risk.

This sounds worth suffering the three hours of blood, sweat and tears! I usually like Russian cinema because of its intensity and this sounds precisely like a film representing the best of that tradition. And besides this, as a historian I have suffered and survived such scenarios in my mind for almost all of my life…

The question that drives me though is how to happen upon this film? Where did you see it? DVD?

If that’s your response after reading this, then you are definitely the audience for this movie. It’s certainly an experience.

I saw it streaming on Netflix, of all places. It’s been out and about for two-ish years now, depending on the country, so you should be able to dig it up.