Hearts and Minds is a polemic, a propaganda piece, a one-sided story, an unbalanced, unfair cry of anguish at an angry, distorted vision of America.

Hearts and Minds is a polemic, a propaganda piece, a one-sided story, an unbalanced, unfair cry of anguish at an angry, distorted vision of America.

Hearts and Minds is a brilliant, nuanced, Oscar winning documentary released in ’74 that for the first time showed the American public the reality of what their war in Vietnam was doing to the people who lived there.

Which statement do you agree with? Most folks pick only one. From the time of its release until today, Hearts and Minds has split opinions on its value and its methods.

I think both statements are true. Not in a weak-kneed, meet-in-the-middle kind of way, but literally. Hearts and Minds is a brilliant, necessary movie, with no interest in “balance.” Director Peter Davis didn’t set out to tell two sides of the Vietnam War story. As far as he was concerned, the American people had been hearing only one side—the government’s side—for the entirety of the conflict. He made Hearts and Minds to show a different reality.

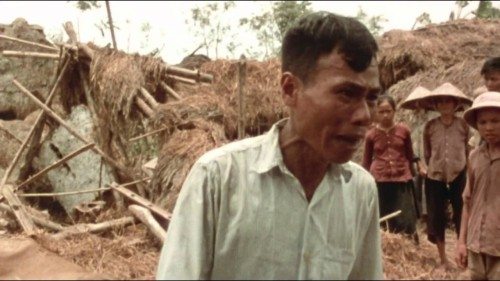

And boy does he. Hearts and Minds was a massive wake-up call when it was released. The news was the only news in those long ago days before the interwebs, and the news didn’t show the Vietnam as known by its people. The Vietnamese, north and south, were but pawns in a political game, and that’s how they were reported on. They were generalizations. They were, in short, not human beings.

Hearts and Minds spends much of its time righting this wrong, showing lengthy interviews with Vietnamese unaffiliated with any army, all of whose lives have been shattered. Two old women cry over their lost sister, killed by a bomb. A man laments the loss of his house and livelihood. Another weeps telling how his children and mother were blown up. A boy holds a photo of his dead father and cries over his coffin. A coffin maker says he can’t keep up with the demand for child-sized coffins, and that the really poor can’t pay for coffins anyway. A young girl runs naked down a road, her skin burning with napalm (in a famous photo come to life). A mother of a dead south Vietnamese soldier flings herself into her son’s grave as men pull her out and shovel in dirt.

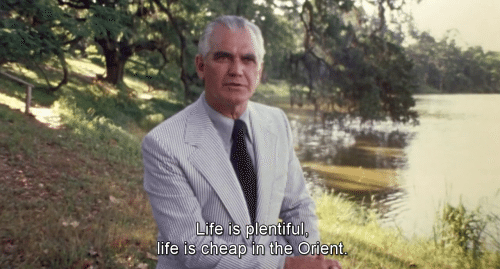

This last scene is followed by the well-coifed General Westmoreland, commander of miitary operations in Vietnam from ’64 to ’68, saying, calmly, knowledgeably, “The Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as the westerner. Life is plentiful, life is cheap in the Orient.”

Life is cheap in the Orient. Says the man who ran the war for four years. And he’s not a war criminal because…?

Well. Because money. Because power. Because America.

Davis’s movie is the blueprint for many modern documentaries, in particular the work of Michael Moore, documentaries we might more exactly call filmic op-eds. Documentarians like Davis and Moore aren’t putting up a pretense of neutrality with their work. Their movies have plainly political aims. Complaining that they aren’t “fair” is just the easiest way to avoid discussing their content.

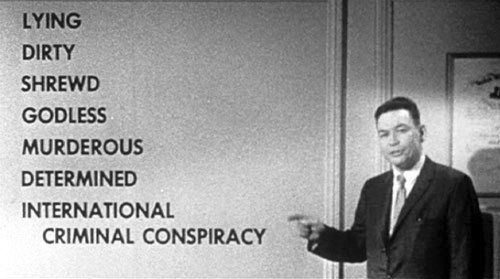

The Vietnam war was predicated on a series of lies promulgated by, according to interviewee Daniel Ellsberg, five presidential administrations, Truman’s through Nixon’s. By the time Hearts and Minds came out in late ‘74/early ’75, American troops had been out of Vietnam for over a year, and the final toppling of the American backed South Vietnamese government was about to take place in April, ’75. Many Americans were well aware they’d been lied into an unwinnable war of imperial agression. But not all of them.

Davis interviews an American couple whose son died in Vietnam. They have nothing bad to say about the war, about how their son died, or about Nixon and the American government in general. Davis even puts up on-screen “Filmed in 1973,” presumably to show that, even mid-Watergate scandal, some people refuse to believe they’re being led by liars and criminals. Davis lingers on the couple for a long time, the father talking and talking, the mother absent-mindedly touching a model fighter plane. It’s a terribly sad scene.

Made when it was, Hearts and Minds is very unlike modern documentaries with its long takes and lack of narration. Davis lets people talk until they’re done talking, then keeps the camera rolling. He’s heard almost not at all, aside from a few questions he asks.

Two pilots are interviewed at length. One explains his job as a bomber as a purely technical exercise, a test of skill in flying a plane and dropping explosives on designated targets. His plane is long gone by the time of impact. He doesn’t hear the explosions, doesn’t see the blood, doesn’t see people at all from his height. At most he sees villages, when villages are what he’s bombing. At first you’re not sure how he feels about any of this, but by the end of the film he’s in tears. Have people learned anything from this war? He thinks they’ve learned nothing but how to ignore what’s in front of them.

The other pilot, George Coker, a prisoner of war for six years, is seen at a homecoming celebration where he gives a speech about the man America made him. He’s more than willing to return to the fight, if asked. When speaking at a grade school, a kid asks him what Vietnam, as a country, was like. Says Coker, “If it wasn’t for the people, it would be very pretty. The people there are very backwards and primitive and make a mess out of everything.”

He’s the only soldier interviewed with anything good to say about the war. Others talk passionately about their love of country and how it was shattered by their experiences. Most are shown in close-up for the first half of the film, and only later revealed to be in wheelchairs or missing limbs. Manipulative? Sure. Welcome to filmmaking.

Still other soldiers are interviewed on the front lines, one group behind a wall they jump up to fire over between answers, in what I swear are outtakes from Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket. None of these soldiers has any coherent answer to what they’re fighting for.

Davis isn’t subtle in his critique of American power. Intercut throughout are scenes from war movies, from WWII dance numbers to battle scenes to one very creepy moment from The Manchurian Candidate. He brings us to an Ohio high school where a group of football players is first seen in church and told that however important winning a football game is, winning the game of life is the real goal. Next we catch up with them in a locker room, their coach firing them up for victory, and finally we get shots of the football game, the strutting cheerleaders, the cheering crowd—America! Boom! Pow!

Critics of Hearts and Mind point to its lack of an in-depth discussion of the war, but they’re missing the point. It’s not an examination of policy, it’s an examination of people, primarily the Vietnamese, but Americans too. It’s about the different ways this war has devastated the people of two countries. And it’s about the liars and opportunists who made it all possible.

Daniel Ellsberg sums it up by saying America wasn’t fighting on the wrong side of the Vietnam War; “We were the wrong side.”

There are two sides to every story, but the truth is the truth (deep, spiraling philosophical conversations aside). Davis’s movie doesn’t offer a “balanced” take on the waging of the Vietnam War, because there is no balanced take. It was a great evil, one that had yet to be fully exposed. He took it upon himself to expose it. The result is a powerful, horrible, deeply unsettling film.