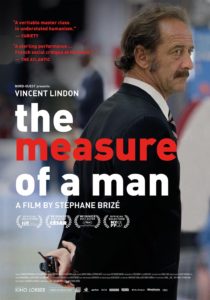

The subtle yet insistent, small yet endless ways bureaucracy crushes our souls, and how we do or do not respond, is the subject of director Stéphan Brizé’s new movie, The Measure of A Man (La Lois du marché). The man whose response is to be measured is Theirry (Vincent Lindon, who won Best Actor at Cannes ’15 for his performance), an average sort of 51 year-old whom we meet at a low point. He’s been out of work for eighteen months and spent the last four, on the advice of the unemployment office (or its French equivalent), training to be a forklift operator, a job for which no one will hire him without past construction site experience. So if that’s the case, why on earth did they tell him to take the four month training course? Good question. The man Theirry talks to agrees this wasn’t the best use of Theirry’s time, yet never quite takes responsibility for so carelessly screwing him over.

The subtle yet insistent, small yet endless ways bureaucracy crushes our souls, and how we do or do not respond, is the subject of director Stéphan Brizé’s new movie, The Measure of A Man (La Lois du marché). The man whose response is to be measured is Theirry (Vincent Lindon, who won Best Actor at Cannes ’15 for his performance), an average sort of 51 year-old whom we meet at a low point. He’s been out of work for eighteen months and spent the last four, on the advice of the unemployment office (or its French equivalent), training to be a forklift operator, a job for which no one will hire him without past construction site experience. So if that’s the case, why on earth did they tell him to take the four month training course? Good question. The man Theirry talks to agrees this wasn’t the best use of Theirry’s time, yet never quite takes responsibility for so carelessly screwing him over.

This is the first of a series of small humiliations that make up the first half of the film. Brizé shoots in a modern, digital style, with brightly lit rooms, handheld camera, with Theirry often in profile. There’s little in the way of framing or staging that feels cinematic. It’s a style meant to evoke realism, and in that it works. Scenes feel less like movie scenes and more like fly-on-the-wall observations of people suffering though real sitations. Not my personal favorite style of movie-making, but one with a slowly building, subtle power, at least in the case of The Measure of A Man.

Theirry is married with a learning-disabled teenage son. They’re in danger of having to sell their apartment. Theirry can’t seem to get hired anywhere.

Until at last he gets a job as a security guard in a huge supermarket, and finds himself spending his days taking hapless thieves—customers and store employees both—into a small room, forcing them to admit to their petty thefts and, lest the police are called, pay for whatever they failed to steal.

From humiliated to humiliator. Theirry’s measure is taken by how he deals with his new position.

Brizé’s style is one of small moments, steadily accumulating. Nothing big and dramatic in here. No emotional speeches of any kind, only the most typically mundane conversations you can imagine. Our everyday life, in other words. It gives the movie a casual, almost accidental feel, at least within scenes. Overall, casual scene follows casual scene in a cafefully constructed story, building to a finale consisting of another simple, small action, but one with great import for Theirry’s future.

Everything that happens in here feels so mundane and ordinary it’s easy to overlook the movie’s point, which point is that very fact: oppression isn’t Big Brother with his boot on your face, it’s the friendly, bussinesslike woman at the bank explaining why your best option is to sell your home to pay off your debts, it’s the dance class instructor making clear your inability to move with grace, it’s watching the face of your fellow employee when it’s explained that because she was caught trying to reuse a few customer coupons, she’s going to lose her job of twenty years.

Is there any way out? A way to resist? To fight back? A small one, maybe. What happens next is anyone’s guess.

Interesting. This would make a good double bill with the film I’m posting about on Monday…

I saw your title and for a second thought you’d watched the same movie. But for the rest of the world, you’ll just have to wait for monday to know what we’re talking about. Suckers!