According to Muhammad Ali, he was the Greatest. Not the greatest boxer, though that, too, but the capital G Greatest, full stop. And the crazy thing is, he was the Greatest. Who but Ali? You’d think the man who talked loudest and longest about being the Greatest would be anything but, but if anyone was like nobody else, it was Ali. Never has a man talked more shit about his opponents and spent more time praising his own greatness and still come off as, in some crazy alternate Earth way hitherto unknown to our planet, the humble underdog. How did he do it?

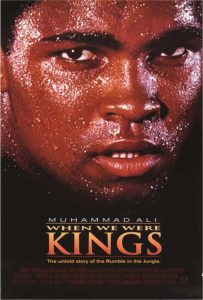

When We Were Kings, the Oscar winning doc from ’96, chronicles the Rumble in the Jungle, Ali’s fight with George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, in ’74, for the heavyweight title, the one Ali used to hold in the ‘60s, before it was stripped due to his refusal to go to Vietnam. It’s a dynamite documentary. I watched it again for the first time since its release, and it’s at least as good as I remembered. Ali is pure Ali throughout, to the point I began to wonder if we know him as the personality we know because that’s the one he showed the cameras when they were on, or if he was the same no matter who was watching? Watching this movie, I lean toward the latter.

When We Were Kings, the Oscar winning doc from ’96, chronicles the Rumble in the Jungle, Ali’s fight with George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, in ’74, for the heavyweight title, the one Ali used to hold in the ‘60s, before it was stripped due to his refusal to go to Vietnam. It’s a dynamite documentary. I watched it again for the first time since its release, and it’s at least as good as I remembered. Ali is pure Ali throughout, to the point I began to wonder if we know him as the personality we know because that’s the one he showed the cameras when they were on, or if he was the same no matter who was watching? Watching this movie, I lean toward the latter.

Director Leon Gast originally went to Zaire in ’74 to film the concert being staged as a lead-in or adjunct to the fight, but when the ruler of Zaire, Mobutu Sese Seko, declared the concert free, there was no money to pay for a documentary. Meanwhile, owing to a cut above his eye Foreman sustained sparring, the fight was postponed for six weeks, and Gast started shooting a doc on Ali and the Rumble. He didn’t finish his movie until 22 years later. It was worth waiting for.

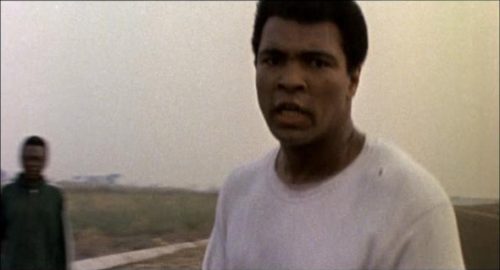

Ali is an unstoppable force. He talks without pause, never seeming to tire. He rhymes up a storm. How does he know he can beat Foreman? Let him explain: “I done something new for this fight. I done wrestled with an alligator. That’s right. I have wrestled with an alligator. I done tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail. That’s bad! Only last week I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalized a brick. I’m so mean I make medicine sick!”

Foreman at the time was a quiet, brooding character, who arrives in Zaire with his pet German Shepherd on a leash. Turns out German Shepherds were police dogs used by the Belgians when they controlled this part of Africa. Not the best image to project. On top of that, many of the Africans assumed Foreman was white until they saw him. No matter Foreman’s color and heritage, everyone was rooting for Ali.

A little of Ali’s history is covered, his early fights, his opposition to Vietnam, his joining the Nation of Islam and changing his name from Cassius Clay, but only in brief. The focus here is on the fight and what it means. Black consciousness and history forms the backdrop, with performances by James Brown, B.B. King and others interspersed with the story of the fight.

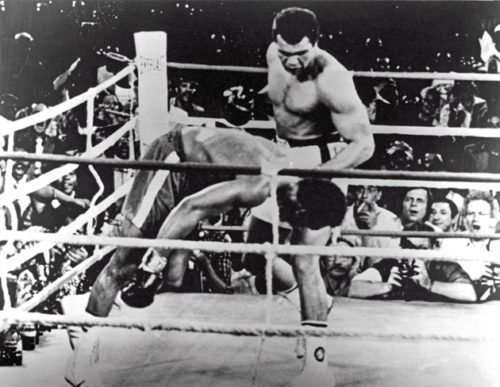

On hand for current (as in ’96) interviews are Spike Lee, who laments the youth of today’s ignorance of Ali, Malcolm X, and essentially all history pre-yesterday, and writers Norman Mailer and George Plimpton, who were in Zaire covering the fight. Both have a way with words when it comes to boxing. Neither man expected Ali to win. No one who knew boxing at the time did. Foreman was simply too strong. There’s a photo of the end of the fight, Foreman going down in the foreground, and we zoom in to see, outside the ring, their mouths hanging open in surprise, Plimpton and Mailer.

When We Were Kings works so well in part because it’s so focused. It digs deeply into Ali’s mindset at the time, or as deep as Ali lets anyone get, building a picture of the man and his history. Ali felt he was going home by coming to Africa, he was proud of his heritage, the people of Africa thought of him as one of their own. He wanted to bring people together, and did, everywhere he went. At the end, Plimpton relates a speech he saw Ali give, some years later, to a graduating class at Harvard. After inspiring them to use the opportunities they’d been given to make a difference in the world, a kid yells out for a poem, and the room goes quiet. Says Ali, “Me, we.”

The Rumble was both a culmination and a new beginning for Ali. He regained the title, and in so doing became the most famous athlete in the world. He wrote a book called The Greatest, and then he made a movie out of it.

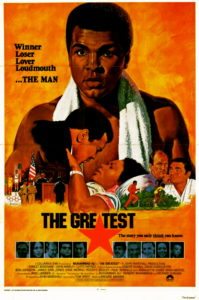

The Greatest came out in ’77 and I’d never heard of it until I saw it last night. It’s an odd bird. It’s mostly directed by TV veteran Tom Gries, best known for the ’68 Charlton Heston western, Will Penny. Gries died during production, and an uncredited Monte Hellman finished the film. It was written by once blacklisted writer Ring Lardner, Jr., (of M.A.S.H. fame). It stars Muhammad Ali playing himself, aside from a few scenes early on when young actor Chip McAllister plays an 18 year old Cassius Clay.

The Greatest came out in ’77 and I’d never heard of it until I saw it last night. It’s an odd bird. It’s mostly directed by TV veteran Tom Gries, best known for the ’68 Charlton Heston western, Will Penny. Gries died during production, and an uncredited Monte Hellman finished the film. It was written by once blacklisted writer Ring Lardner, Jr., (of M.A.S.H. fame). It stars Muhammad Ali playing himself, aside from a few scenes early on when young actor Chip McAllister plays an 18 year old Cassius Clay.

No surprise, Ali plays Ali to a tee. You believe every minute. He’s exactly like he is. The movie tells the story of his life, from his winning gold in the Rome Olympics at age 18 to his winning the heavyweight title in Zaire in ’74. There’s nothing exactly dramatic in The Greatest. It’s not just that you know what’s going to happen, it’s that scenes are written and played as snapshots rather than scenes. Moments happen, all with great significance, none with any real context. It’s not so much a history of Ali’s life as a collection brief incidents, each allowing Ali’s greatness to shine.

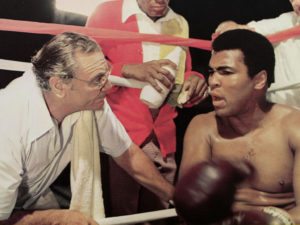

Intercut throughout is footage from Ali’s actual fights, lending the movie a certain amount of realism, though when midway through real fights we cut to Ali’s corner to find Ernest Borgnine yelling encouragement, the realism fades a bit.

That’s right, the Borgnine is on hand as Ali’s trainer. Robert Duvall turns up in a couple of scenes, as do Ben Johnson, Paul Winfield, and, as Malcolm X, James Earl Jones.

Despite The Greatest not really functioning as a story, it remains fascinating, I think for no other reason than that Ali is the center of attention. Ali the man, Ali the character, Ali the Greatest, whoever he is, when he’s onscreen, there’s no one you’d rather be watching, it doesn’t matter what he’s doing or who he’s playing against. Like every other filmed moment of Ali’s life, this movie exists for no other reason than to give Ali yet another platform on which to proclaim his greatness. But what a greatness it was. He didn’t take shit from anyone. He stood up for what he believed in, no matter the consequences. He was and is an inspiration.

The Greatest ends up being an oddly sweet and charming movie. It’s not a very good movie. I’m not here to recommend it. If you want to gain insight into the man, if you want to come away saying, “Damn right, Ali is the Greatest!” you’re much better off watching When We Were Kings. But then again, maybe The Greatest offers its own kind of insight. Ali compels attention, no matter the context. So no, you needn’t bother watching The Greatest, but if you do, you’ll probably enjoy yourself.

Very nice article on a man who, for most of the ’70s was THE MAN. Ali was more than a sports figure, he was a true icon, and deservedly so.

I’ve seen both of these and agree that When We Were Kings is the far superior movie. The Greatest I saw at some point on television when I was young, and assumed it was a made-for-TV movie. Evidently not!