By definition, the world of noir novels and films is a world dark, bleak, and evil, but nothing I have ever read is more so than William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley. It is a book that howls with fury at the pain of existence, that shakes its drunken fist at the cold, empty, uncaring universe, that unmasks every con and swindle from carny mentalism to psychology to religion on its way to unmasking the greatest swindle of them all—the illusion of free will. It is as grim and depressing a book as anyone ever wrote. In a word, it’s magnificent.

I mean if you like that sort of thing.

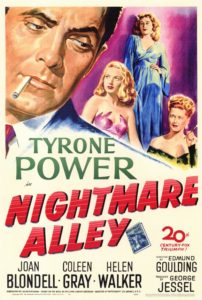

Actor Tyrone Power did. Tired of playing romantic heroes, he bought the film rights to the book so he could play the lead role, sideshow huckster and soon-to-be master mentalist Stanton Carlisle. That so dark a movie was actually made and released in ’47 is a surprise. That it’s as good as it is even more so. It was adapted by screenwriter Jules Furthman, known for The Big Sleep, To Have and Have Not, Mutiny on The Bounty, Rio Bravo, and 114 (!) other scripts, and directed by Edmund Goulding, another man of many credits in the ‘30s and ‘40s. Along with Power, it stars Joan Blondell and Coleen Gray (of Kubrick’s The Killing). Released in ’47, it wasn’t anything like a hit, but over the years its star has risen to the point it’s regularly cited as one of the great film noirs.

Actor Tyrone Power did. Tired of playing romantic heroes, he bought the film rights to the book so he could play the lead role, sideshow huckster and soon-to-be master mentalist Stanton Carlisle. That so dark a movie was actually made and released in ’47 is a surprise. That it’s as good as it is even more so. It was adapted by screenwriter Jules Furthman, known for The Big Sleep, To Have and Have Not, Mutiny on The Bounty, Rio Bravo, and 114 (!) other scripts, and directed by Edmund Goulding, another man of many credits in the ‘30s and ‘40s. Along with Power, it stars Joan Blondell and Coleen Gray (of Kubrick’s The Killing). Released in ’47, it wasn’t anything like a hit, but over the years its star has risen to the point it’s regularly cited as one of the great film noirs.

Those who don’t call it one of the noir greats at least note it’s one of the most demented and sick.

And so it is.

Nightmare Alley tells the story of recently hired traveling carnival employee Stanton Carlisle. He helps Zeena (Blondell) and her alcoholic husband, Pete (Ian Keith) with their mentalist show. Long ago, the couple headlined shows of their own, but Pete’s alcoholism has reduced them to mere carnies. Stanton finds out they owed their prior fame to a complicated and secret verbal code system they refuse to share. He wonders what he could do with such a system. It’s a shame Pete, the useless drunk, is still in the way…

Pete’s exit is one of the best scenes in the movie, aided greatly by actor Ian Keith’s performance. It’s a long, late night back and forth between him and Stanton, a bottle between them. Knowing what happens makes it that much more powerful, like watching a man die in slow motion.

From there, Stanton climbs to the top of the carny scene, then makes his way into higher society with a code-based mentalist show, bringing him fame and riches. Soon he’s latched onto Ezra Grindle, a skeptical business tycoon, and convinced him he can see again his long lost love. How does Stanton find out about Grindle’s personal secrets? By collaborating with Grindle’s psychologist, Lilith Ritter (played with icy evil by Helen Walker). Stanton initially goes to Lilith for help with his own demons, but once he finds he can use her to further his schemes, he does. He doesn’t yet realize that psychology is just another racket, and Lilith a master manipulator. For the elaborate hoax they play on Grindle, Stanton needs the help of his (Stanton’s) wife, Molly (Gray). She’s his partner in the mentalist act, but actually pretending to be the spirit of a man’s dead girlfriend? She’s appalled.

It is appalling, sure, playing on a man’s weaknesses, suckering him to such a degree. But is dressing up as a dead woman and wandering ethereally through a moonlit garden really so awful? As played in the movie, the scene works well enough, with Grindle sobbing on his knees, thanking god and so on, before Molly cracks. But in the book, the sequence is genuinely depraved. Grindle’s girl wasn’t merely a lost love, he got her pregnant, and she died during the back alley abortion he forced on her. Molly plays the dead girl multiple times, in an elaborately rigged room (lights, sound effects, music, etc.) in Grindle’s house. Grindle’s so taken with the illusion he finally snaps—he grabs the “ghost” and tries to screw her.

Power plays Stanton to the hilt. He’s never anything but scheming and dislikeable. Yet he appeals through his confidence and success. If anything, he’s too charismatic. His downfall in the movie is quick, too quick, there’s not enough time to really sink into the mud with him. In the book, he’s hounded for months, years, even, by Grindle’s men. A man so rich, and so deceived, will stop at nothing to exact revenge. Stanton becomes desperate, an alcoholic, a murderer.

The book is pure noir in its fatalistic outlook. Stanton is doomed from page one. Gresham uses the Major Arcana of the tarot as chapter titles to drive home the inevitability of Stanton’s fate. The cards come up again and again in the telling, with Stanton dubbed The Hanged Man—the title of the final chapter. Gresham himself was no less doomed than Stanton. He led a tumultuous life ending with suicide at age 53. An earlier suicide attempt twenty-odd years earlier failed. Nightmare Alley is his first novel. He wrote only one other, as well as some non-fiction. He was an alcoholic fascinated by spiritualism, religions, psychology, but found all of them lacking. He dedicated Nightmare Alley to his second wife, Joy Davidman. She left him a few years later to marry author C.S. Lewis (a relationship dramatized in the ’93 film Shadowlands, with Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger). When Gresham’s body was found, he had business cards on him reading: “No address. No phone. No business. No money. Retired.”

Nightmare Alley was the first book to popularize the term “geek” for the carny act of a wild man biting the heads off chickens and snakes. Gresham had met a man, an ex-carny, who told him many tales of life on the road, but it was the geek, and how he was made, not found, that stuck with Gresham, that drove the writing of the book. In both book and movie, it’s explained simply. Find a drunk, ask him to wear a costume and “play” the geek until they find a “real” one. Give him a bottle of liquor a day and a place to sleep, have him use a razor blade to cut the chicken’s neck, pretend to drink its blood. A week later tell him faking it’s no good, they’ll have to get a real geek. Envisioning the horrors of the DTs without his daily bottle, the fake geek becomes the real one. As an alcoholic himself, this terrified Gresham.

The movie makes smart use of sound to highlight Stanton’s similar fear. Early on, the geek runs wild one night, howling until he gets his bottle. Throughout the rest of the movie, every time Stanton hits a dramatic low point, faintly on the soundtrack are heard the howls of the geek, fighting their way into Stanton’s consciousness.

There can be but one ending to this story, and Gresham takes us all the way there. In the movie version, the finale is altered to one perched somewhere between “ambiguous” and “hopeful.” It’s a bit of a cop-out, especially in a noir, where bleak endings are the norm. But given all the shady business that comes before, Power and the filmmakers must have wanted to leave audiences with at least a glimmer of hope and the potential for redemption. In that way, Nightmare Alley the movie falls short of the pure noir worldview, the theme of which was best summed up by author James Ellroy: “You’re fucked.”

I haven’t watched this one in ages. Might be time to revisit it.

Yep. And if you’ve got any book reading time these days, read it. It’s something special.

I disagree that in the book Grindle’s men hound Stanton. That’s in his mind. (I do admit I have 17 pages left to go, but it’s clear so far that he is imagining a lot of the “hounding.” This is made explicit in the scene in the club.

Excellent point. Though I’d just rewatched the movie before writing this, I haven’t read the book for a few years. You’re right, he imagines Grindle’s men are everywhere, which makes Stanton’s downfall that much more desperate and painful and horrible. His fantasies of persecution are surely more terrifying than if his persecution had been real. The real horror is within our own minds.

Also–you have only 17 pages left? Hurry up! The end is perfect.

Thanks for answering! (I have come back to the page because the new film is coming out.) No one else I know has read the book unfortunately. Yes, the ending is unbeatable.